Reproductive System, Female

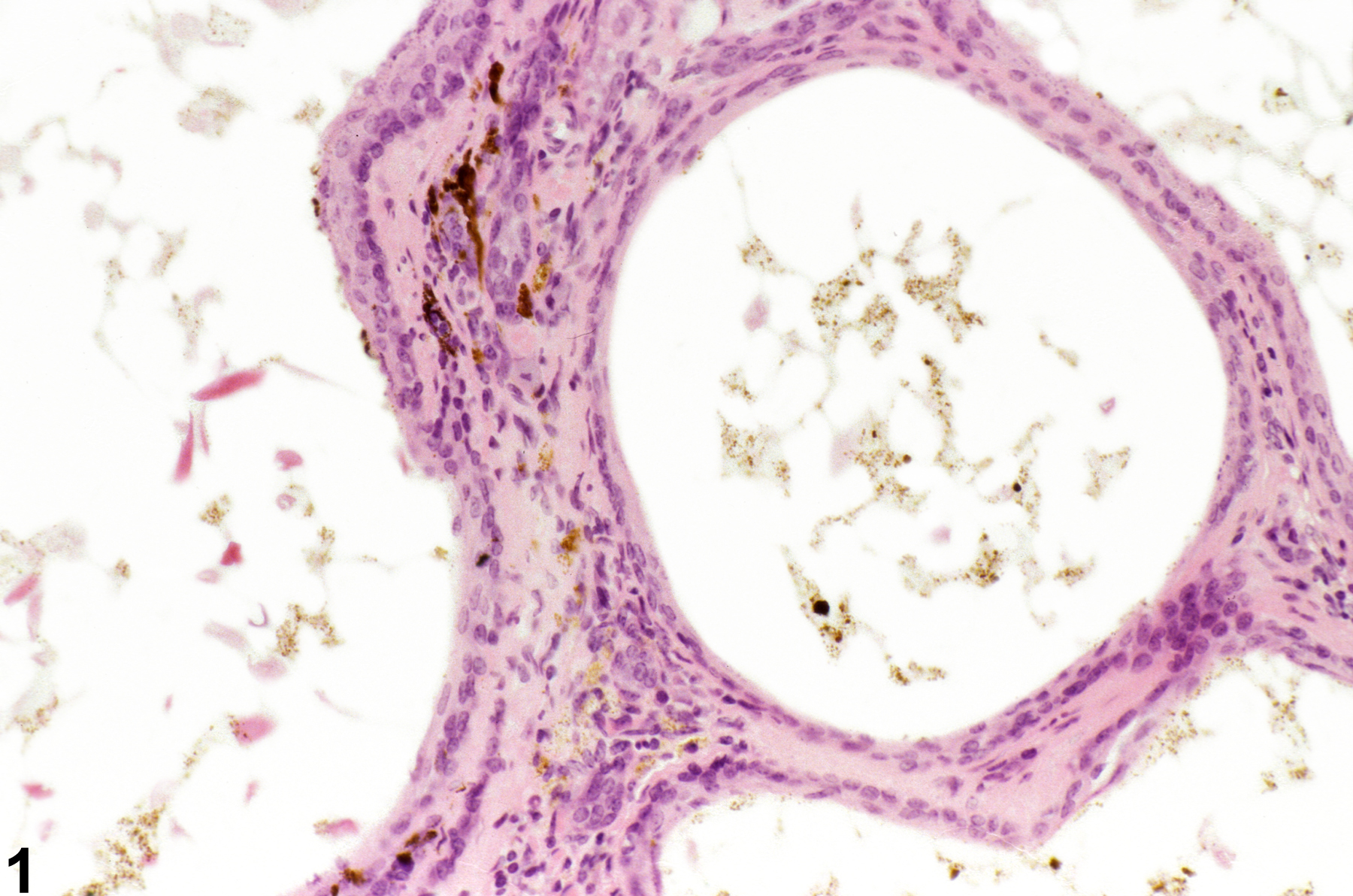

Clitoral Gland - Pigment

Narrative

Clitoral gland pigmentation (Figure 1 and Figure 2) may be an age-associated degenerative change but may also be seen as a sequela of cell damage (ceroid or lipofuscin) or hemorrhage (hemosiderin). It often accompanies clitoral gland atrophy. Lipofuscin has been reported in the cytoplasm of individual acinar cells.

Pigment should be diagnosed when it is considered to be relevant to the study (or if it is unclear whether it is relevant to the study) or if it is unusually prominent. Not all pigments have to be diagnosed, as some are ubiquitous in aging animals or are secondary to another disease process (e.g., hemorrhage) and not toxicologically meaningful. The pathologist should use his or her judgment in deciding whether or not the pigment should be diagnosed. When pigment is seen concurrently with atrophy, the pigment should not be diagnosed separately but may be described in the pathology narrative. Definitive pigment identification is often difficult in histologic sections, even with a battery of special stains. Therefore, a diagnosis of “pigment” (as opposed to diagnosing the type of pigment, e.g., hemosiderin or lipofuscin) is most appropriate. The pathology narrative should describe the morphologic features of the pigmentation. When pigment is diagnosed, it should be given a severity grade.

Copeland-Haines D, Eustis SL. 1990. Specialized sebaceous glands. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat: Reference and Atlas (Boorman GA, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 279-293.

National Toxicology Program. 1996. NTP TR-451. Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Nickel Oxide (CAS No. 1313-99-1) in F344 Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Inhalation Studies). NTP, Research Triangle Park, NC.

Abstract: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/6046

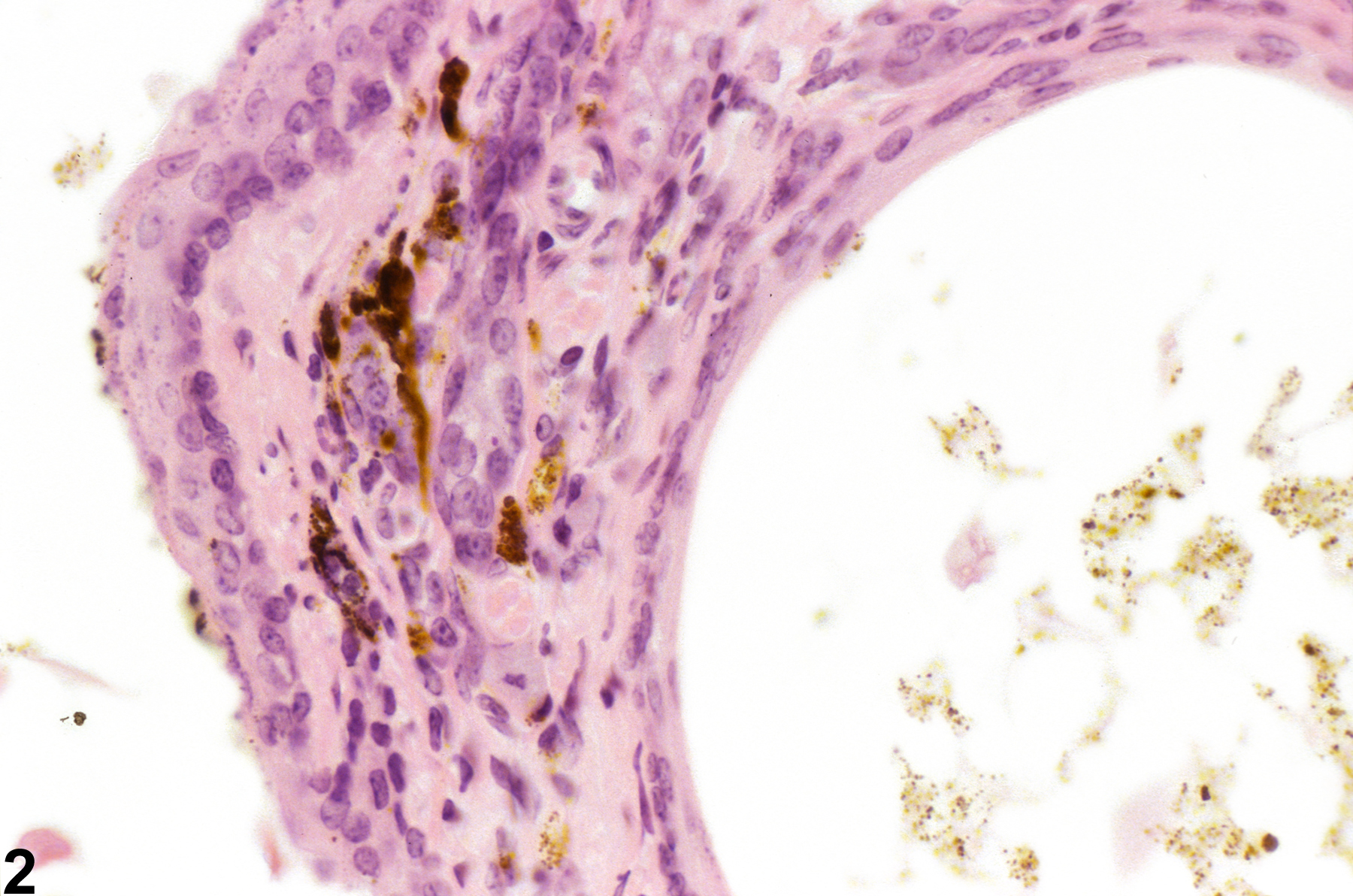

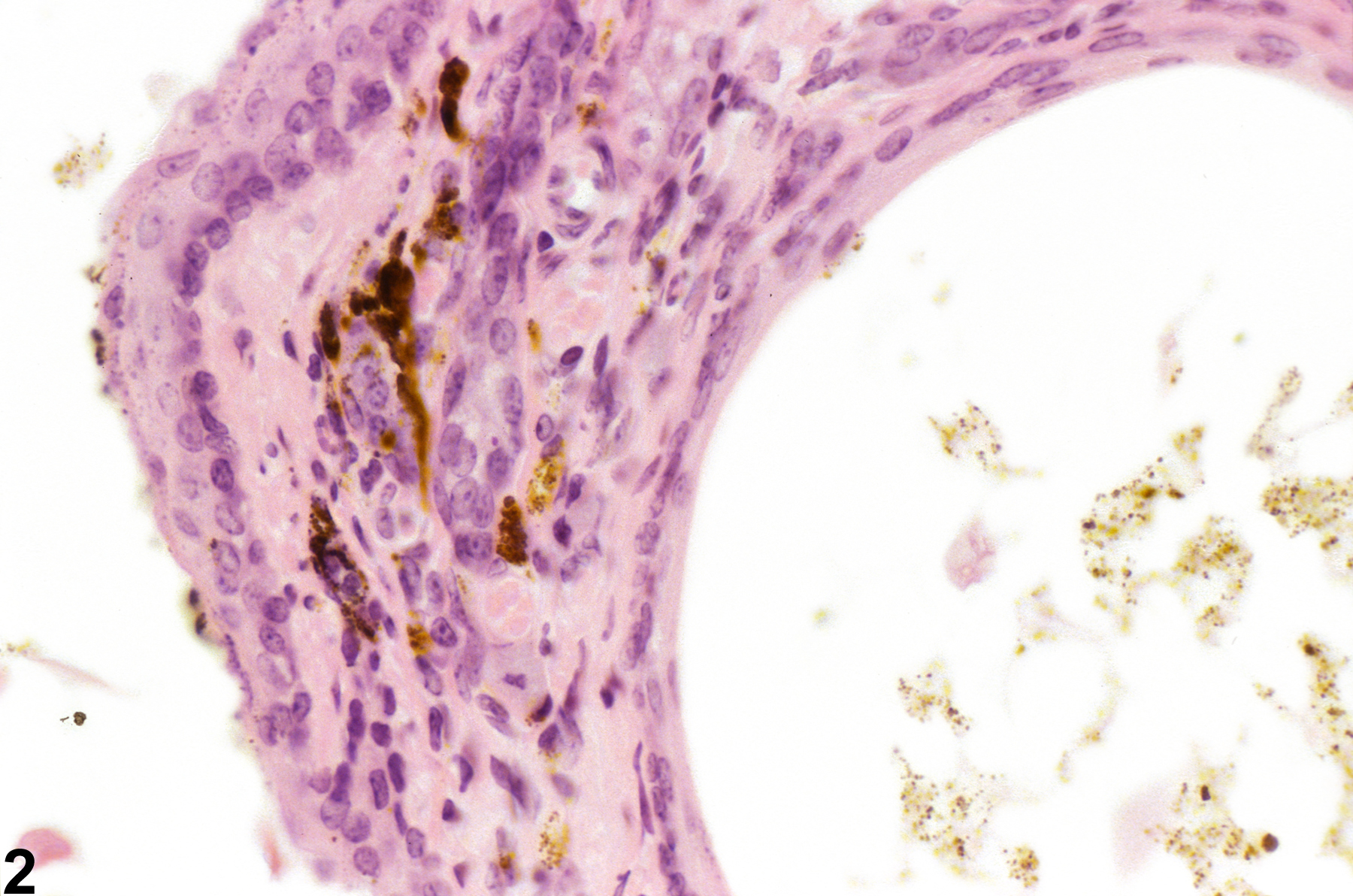

Clitoral gland - Pigment in a female B6C3F1/N mouse from a chronic study (higher magnification of Figure 1). The dilated ducts contain a small number of cells with brown, granular, cytoplasmic pigment and some pale-staining eosinophilic debris, and the stroma surrounding the glands also contains some dark-staining materials.

All Images

Clitoral gland - Pigment in a female B6C3F1/N mouse from a chronic study (higher magnification of Figure 1). The dilated ducts contain a small number of cells with brown, granular, cytoplasmic pigment and some pale-staining eosinophilic debris, and the stroma surrounding the glands also contains some dark-staining materials.