Special Senses System

Lacrimal Gland - Inflammation

Narrative

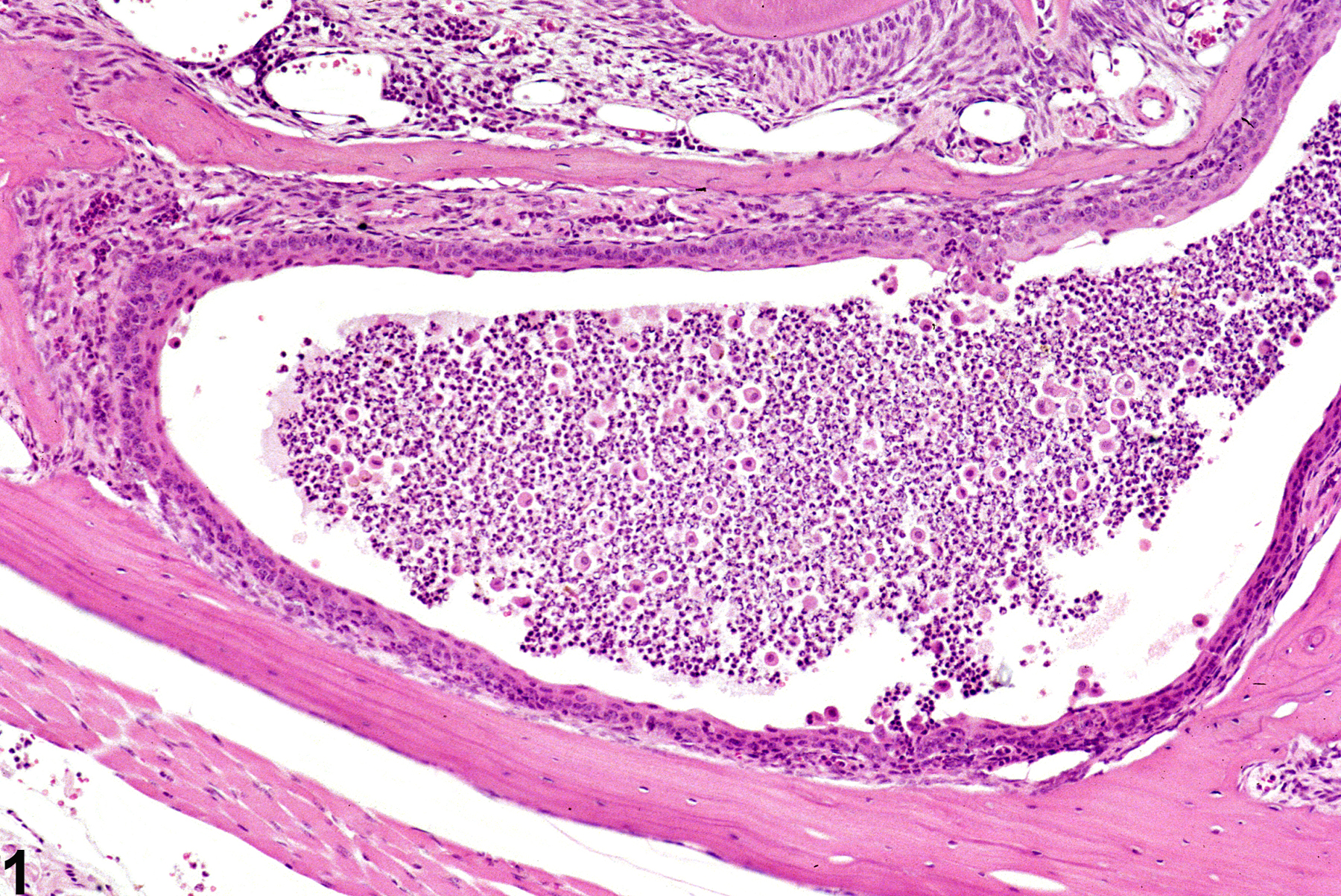

In NTP studies, there are five standard categories of inflammation: acute, suppurative, chronic, chronic-active, and granulomatous. In acute inflammation (Figure 1 and Figure 2), the predominant infiltrating cell is the neutrophil, though fewer macrophages and lymphocytes may also be present. There may also be evidence of edema or hyperemia. The neutrophil is also the predominant infiltrating cell type in suppurative inflammation, however, in suppurative inflammation, the neutrophils are aggregated and many of them are degenerate (suppurative exudate). Cell debris, both from the resident cell populations and infiltrating leukocytes, proteinaceous fluid containing fibrin, fewer macrophages, occasional lymphocytes or plasma cells, and, possibly, an infectious agent may also be present in within the exudate. Grossly, these lesions would be characterized by the presence of pus. In the tissue surrounding the exudate, there may be fibroblasts, fibrous connective tissue, and mixed inflammatory cells, depending on the chronicity of the lesion. Lymphocytes predominate in chronic inflammation. Lymphocytes also predominate in chronic-active inflammation (Figure 3 and Figure 4), but in chronic-active inflammation, there are also a significant number of neutrophils. Both lesions may contain macrophages. Granulomatous inflammation is another form of chronic inflammation, but this diagnosis requires the presence of a significant number of aggregated, large, activated macrophages, epithelioid macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells. Inflammation is differentiated from cellular infiltrates by the presence of other changes, such as edema, hemorrhage, degeneration, necrosis, or other evidence of tissue damage.

Botts S, Jokinen M, Gaillard ET, Elwell MR, Mann PC. 1999. Salivary, Harderian, and lacrimal glands. In: Pathology of the Mouse: Reference and Atlas (Maronpot RR, Boorman GA, Gaul BW, eds). Cache River Press, Vienna, IL, 49-79.

Greaves P. 2007. Nervous system and special sense organs. In: Histopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies: Interpretation and Relevance in Drug Safety Evaluation, 3rd ed. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 861-933.

Abstract: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780444527714Krinke GJ, Schaetti PR, Krinke A. 1996. Nonneoplastic and neoplastic changes in the Harderian and lacrimal glands. In: Pathobiology of the Aging Mouse, Vol 2 (Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Capen CC, Carlton WW, Sundberg JP, Ward JM, eds). International Life Sciences Institute Press, Washington, DC, 139-152.

Lui SH, Prendergast RA, Silverstein AM. 1987. Experimental autoimmune dacryoadenitis. I. Lacrimal disease in the rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 28:270–275.

Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8591907/National Toxicology Program. 1989. NTP TR-352. Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of N-Methylolacrylamide (CAS No. 924-42-5) in F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Gavage Studies). NTP, Research Triangle Park, NC.

Abstract: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/6965National Toxicology Program. 1992. NTP TR-388. Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Ethylene Thiourea (CAS: 96-45-7) in F344 Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Feed Studies). NTP, Research Triangle Park, NC.

Abstract: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/12227Percy DH, Wojcinski ZW, Schunk MK. 1989. Sequential changes in the Harderian and exorbital lacrimal glands in Wistar rats infected with sialodacryoadenitis virus. Vet Pathol 26:238-245.

Full Text: http://vet.sagepub.com/content/26/3/238.full.pdfRahimy E, Pitcher JD III, Pangelinan SB, Chen W, Farley WJ, Niederkorn JY, Stern ME, Li DQ, Pflugfelder SC, De Paiva CS. 2010. Spontaneous autoimmune dacryoadenitis in aged CD25KO mice. Am J Pathol 177:744-753.

Full Text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2913359/

Lacrimal gland - Inflammation, Acute in a male B6C3F1 mouse from a chronic study. Acute inflammation is characterized by predominantly neutrophil accumulations in the lacrimal gland duct.