Reproductive System, Female

Uterus - Dilation

Narrative

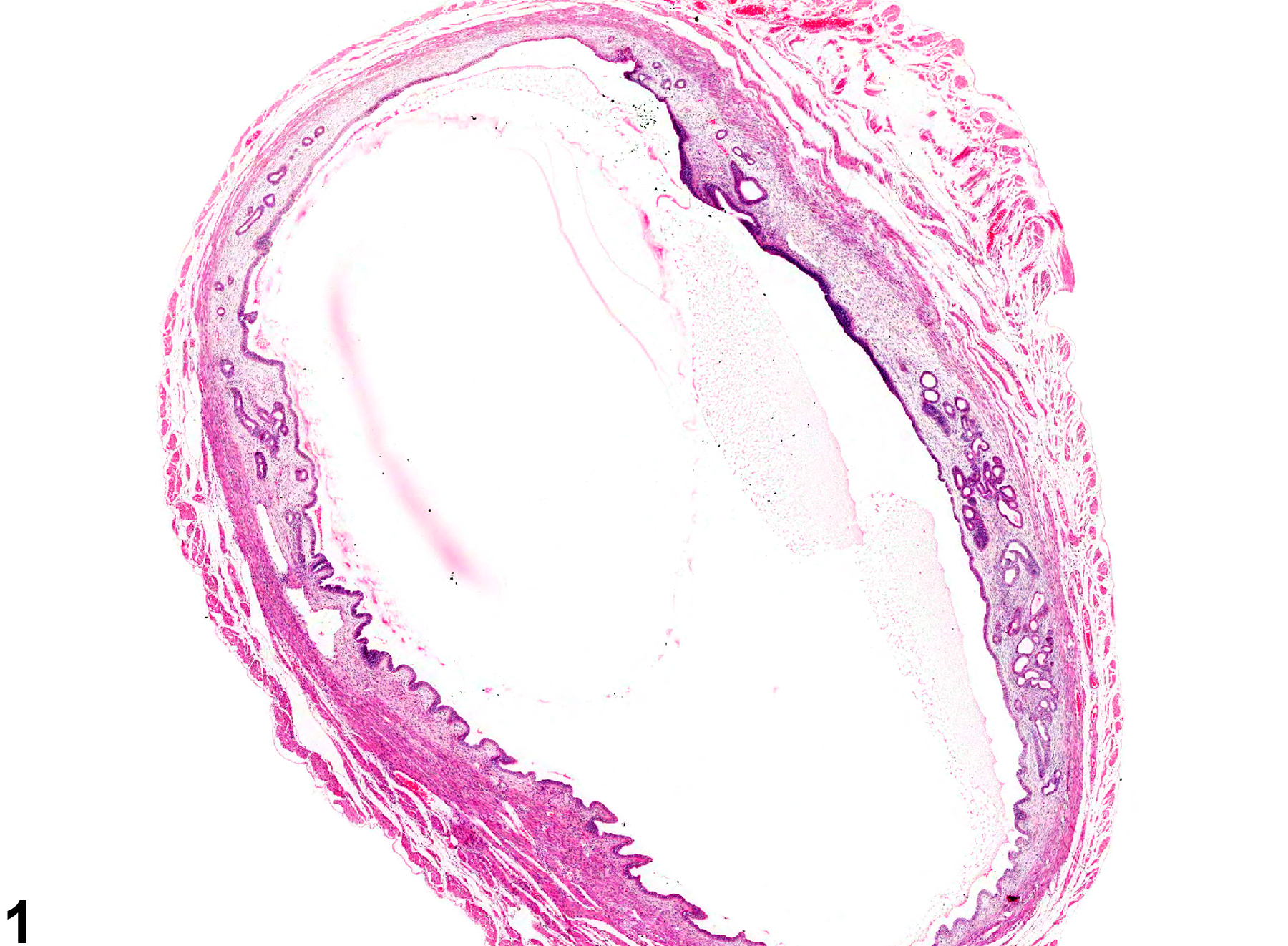

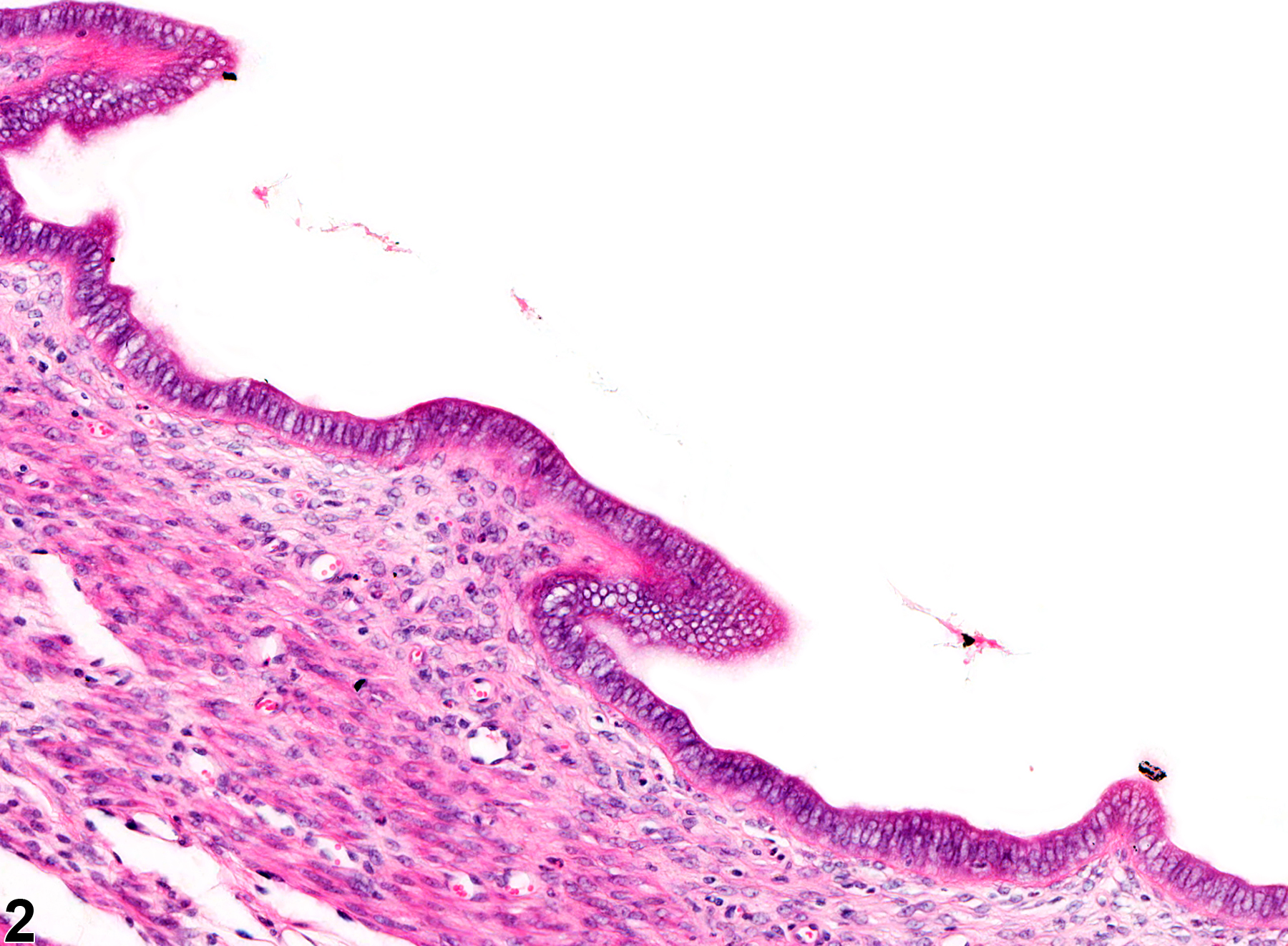

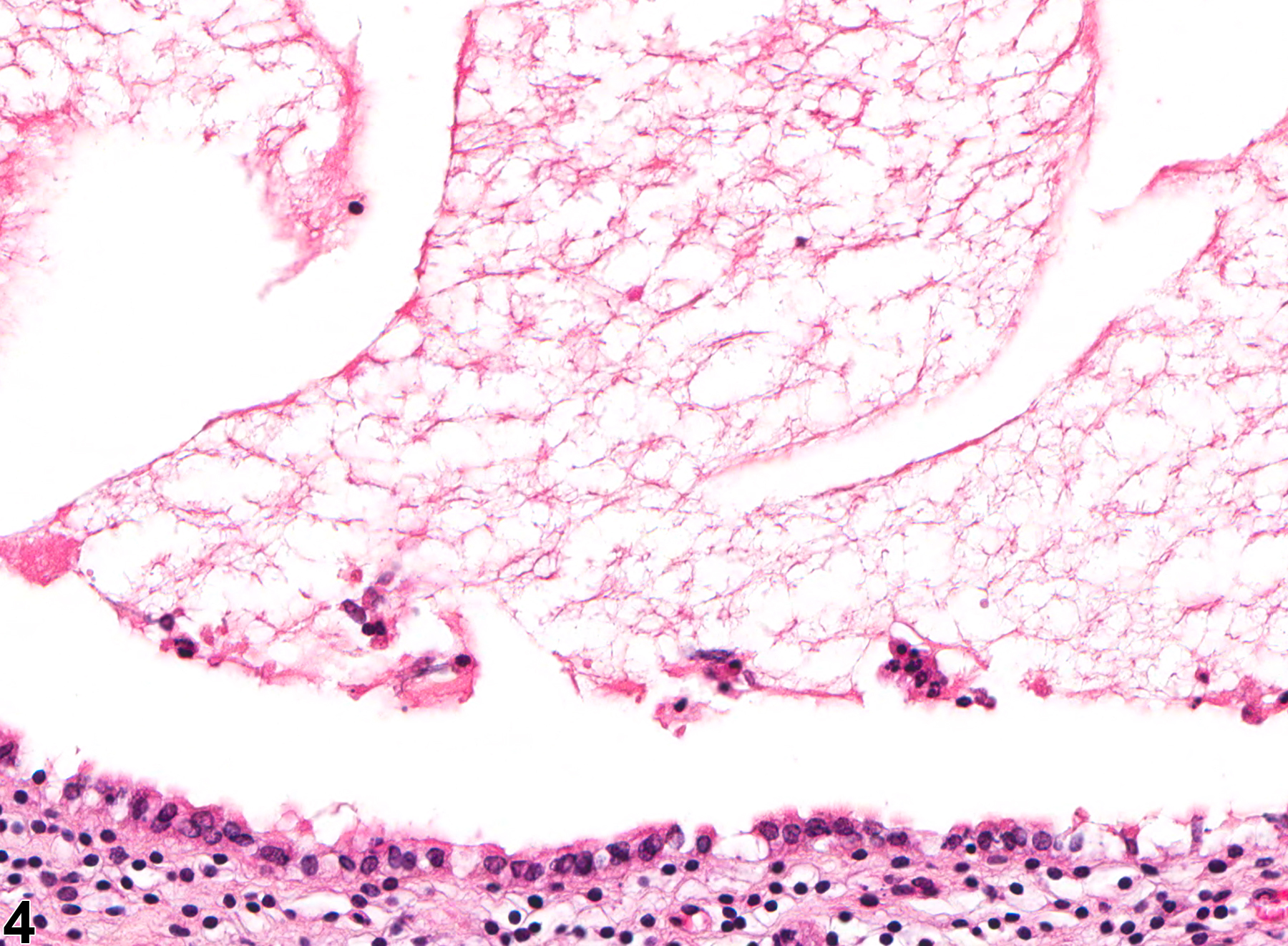

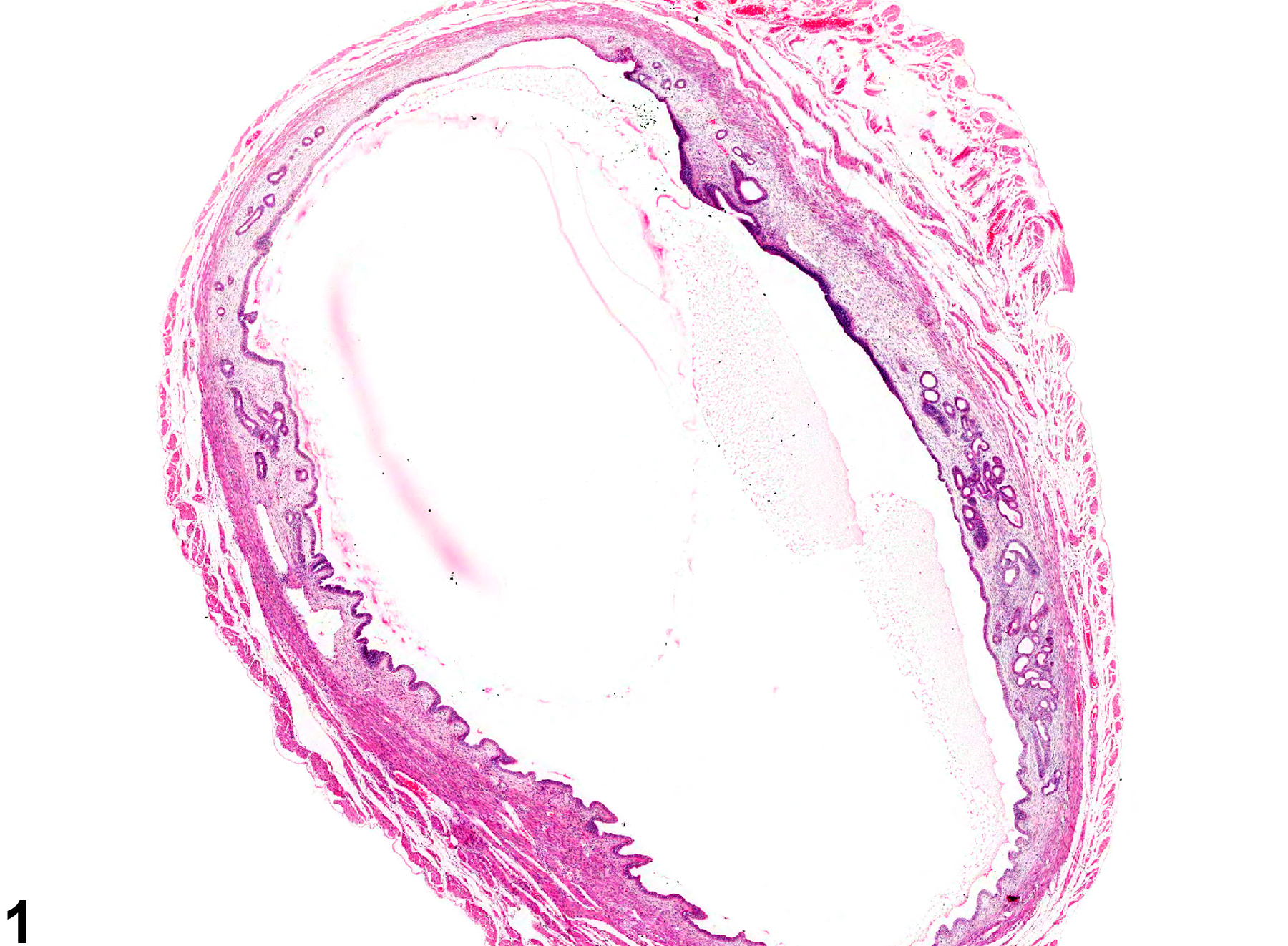

Dilation of uterine horns (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4) is commonly observed at necropsy, and frequently these uteri have accumulations of excessive amounts of fluid within the lumen. Uterine dilation is relatively commonly seen in both rats and mice and may be segmental. Luminal dilation may be associated with stromal polyps or occur secondarily to hormonal imbalances from ovarian cysts or to a prolonged estrus state after cessation of the estrus cycle in aged rodents. Administration of progestins, estrogens, and tamoxifen in rats has been associated with uterine dilation. Luminal dilation is normally observed at proestrus and estrus in cycling rodents and should not be diagnosed. Increased serous fluid production is part of the proestrus phase of the cycle judged by the vaginal epithelium (which shows early keratinization covered by a layer of mucified cells) and should not be diagnosed.

With uterine dilation, the endometrial lining is usually attenuated or atrophic and the wall of the uterus thinned due to the increasing pressure, but in less severe cases the endometrium can be normal (Figure 2). Dilated uterine lumen that is secondary to an inflammatory process such as pyometra should not be diagnosed separately.

Uterine dilation may need to be differentiated from marked cystic endometrial hyperplasia, particularly when only cross-sections of the uterus are examined. In cystic endometrial hyperplasia, there is an increased number of active proliferating glands that may have dilated lumens. In uterine dilation, the uterine lumen is dilated, which could be confused with a single dilated glandular lumen. Therefore, the section must be carefully examined to determine whether the dilated structure is a single uterine gland or is the uterine lumen. The differentiation of these two lesions is more obvious in longitudinal sections of uterus.

Uterus - Dilation should be recorded and graded when not part of normal estrous cyclicity.

Brown RH, Leininger JR. 1992. Alterations of the uterus. In: Pathobiology of the Aging Rat (Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Capen CC, eds). ILSI Press, Washington, DC, 377–388.

Davis BJ, Dixon D, Herbert RA. 1999. Ovary, oviduct, uterus, cervix and vagina. In: Pathology of the Mouse: Reference and Atlas (Maronpot RR, Boorman GA, Gaul BW, eds). Cache River Press, Vienna, IL, 409-444.

Dixon D, Heider K, Elwell M. 1995. Incidence of nonneoplastic lesions in historical control male and female Fischer 344 rats from 90 day toxicity studies. Toxicol Pathol 23:338–348.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7659956Greaves P. 2012. Female genital tract. In: Histopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies: Interpretation and Relevance in Drug Safety Evaluation, 4th ed. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 667-724.

Leininger JR, Jokinen MP. 1990. Oviduct, uterus and vagina. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat (Boorman GA, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 443-459.

Maekawa A, Maita K. 1996. Changes in the uterus and vagina. In: Pathobiology of the Aging Mouse (Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Capen CC, Carlton WW, Sundberg JP, Ward JM, eds). ILSI Press, Washington, DC, 469-480.

Uterus - Dilation of the uterine lumen in a female B6C3F1/N mouse from a chronic study. There is dilation of the uterine horn.