Alimentary System

Esophagus - Hyperplasia

Narrative

Boorman GA, Hong HL, Jameson CW, Yoshitomi K, Maronpot RR. 1986. Regression of methyl bromide-induced forestomach lesions in the rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 86:131-139.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3764933Breider MA, Bleavins MR, Reindel JF, Gough AW, de la Iglesia FA. 1996. Cellular hyperplasia in rats following continuous intravenous infusion of recombinant human epidermal growth factor. Vet Pathol 33:184-194.

Full Text: http://vet.sagepub.com/content/33/2/184Hargis AM, Ginn PE. 2007. The integument. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, 4th ed (McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds). Mosby, St Louis, MO, 1107-1261.

Maraschin R, Bussi R, Conz A, Orlando L, Pirovano R, Nyska A. 1995. Toxicological evaluation of u-hEGF. Toxicol Pathol 23:356-366.

Full Text: http://tpx.sagepub.com/content/23/3/356.full.pdfNelson LW, Kelly WA, Weikel JH. 1972. Mesovarial leiomyomas in rats in a chronic toxicity study of musuprine hydrochloride. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 23:731-737.

Reindel JF, Pilcher GD, Gough AW, Haskins JR, de la Iglesia FA. 1996. Recombinant human epidermal growth factor-1–48-induced structural changes in the digestive tract of cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Toxicol Pathol 24:669-679.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9082544Vinter-Jensen L. 1999. Pharmacological effects of epidermal growth factor (EGF) with focus on the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts. APMIS Suppl 93:40-42.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10424202

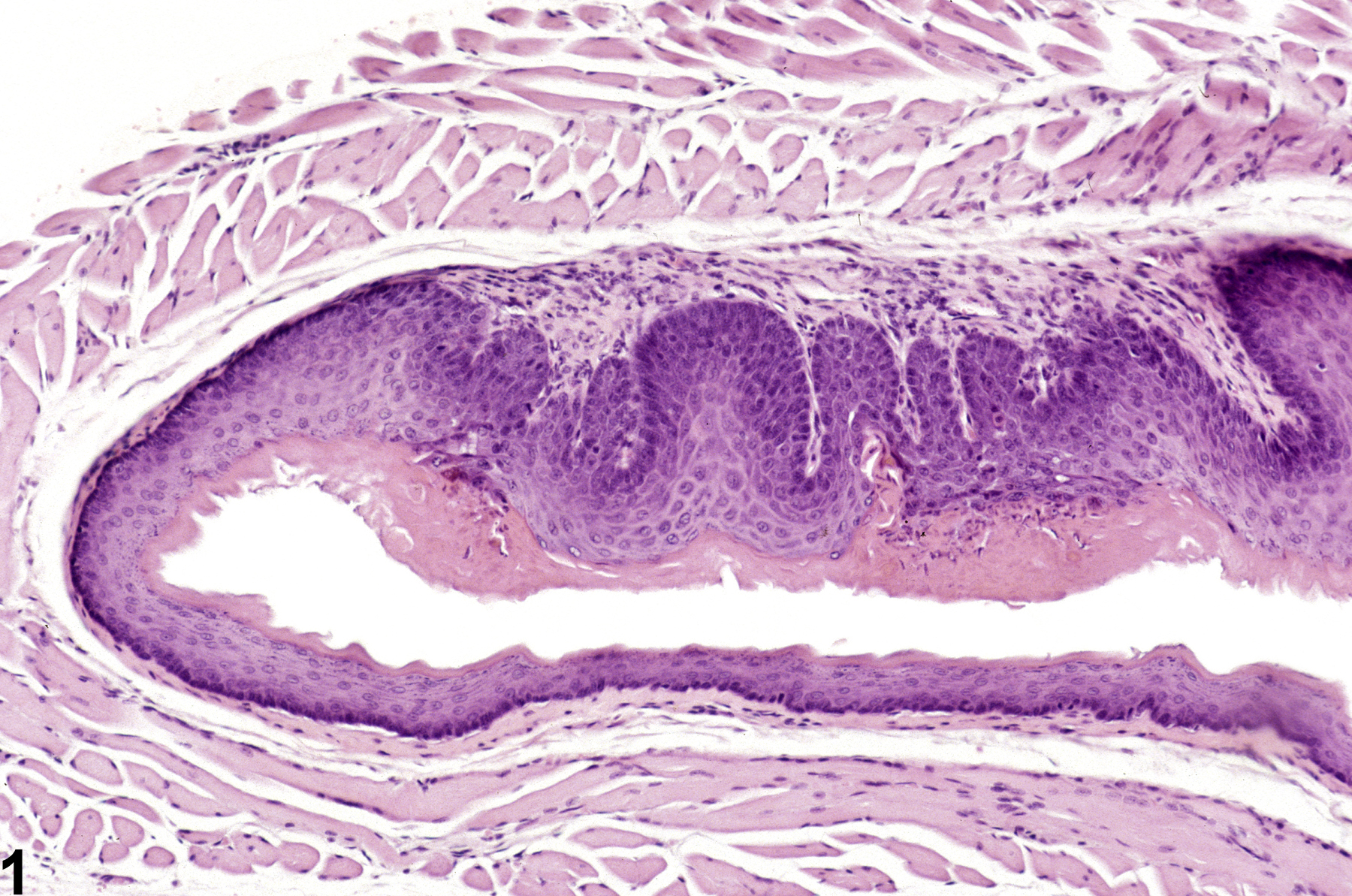

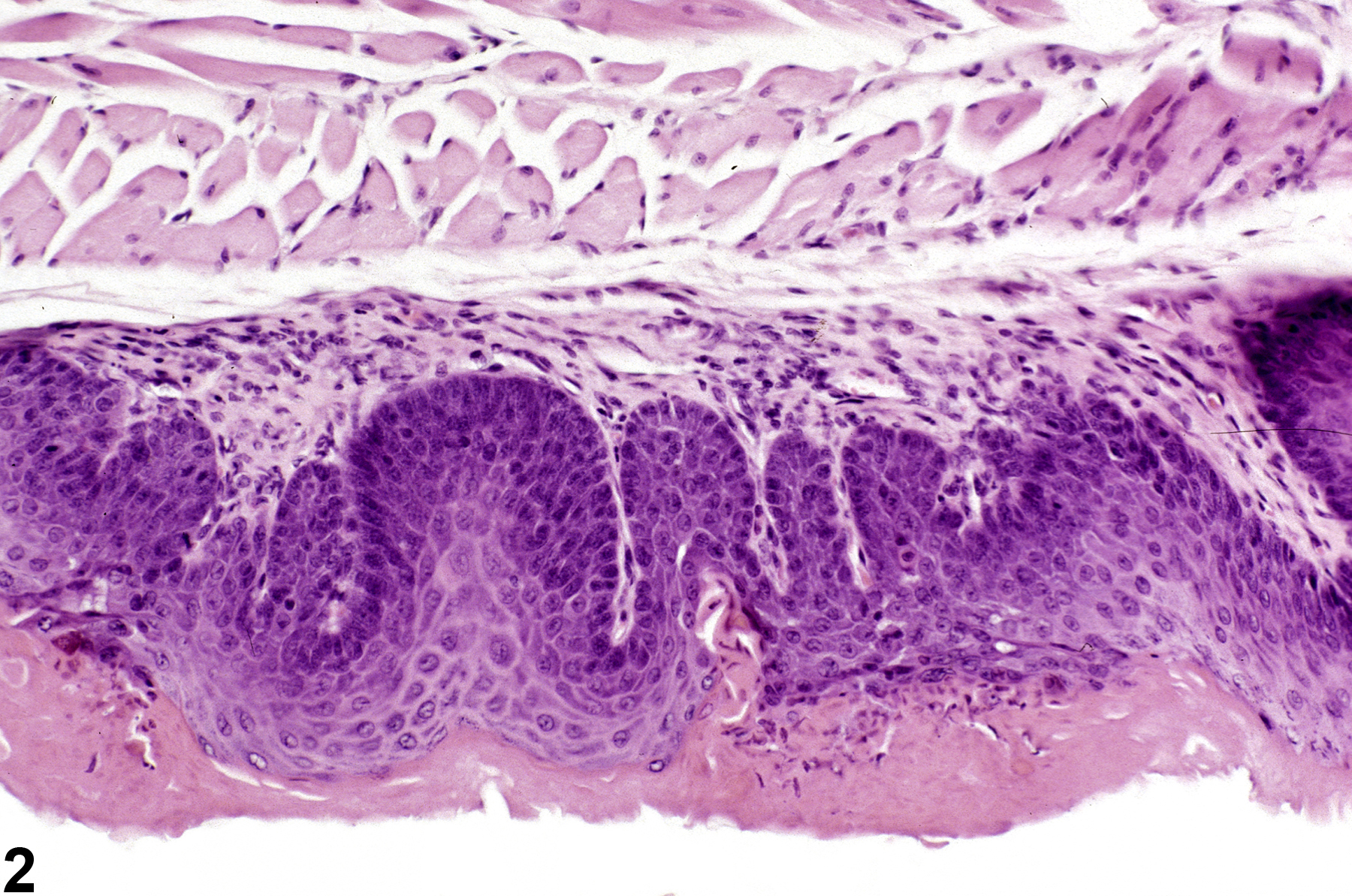

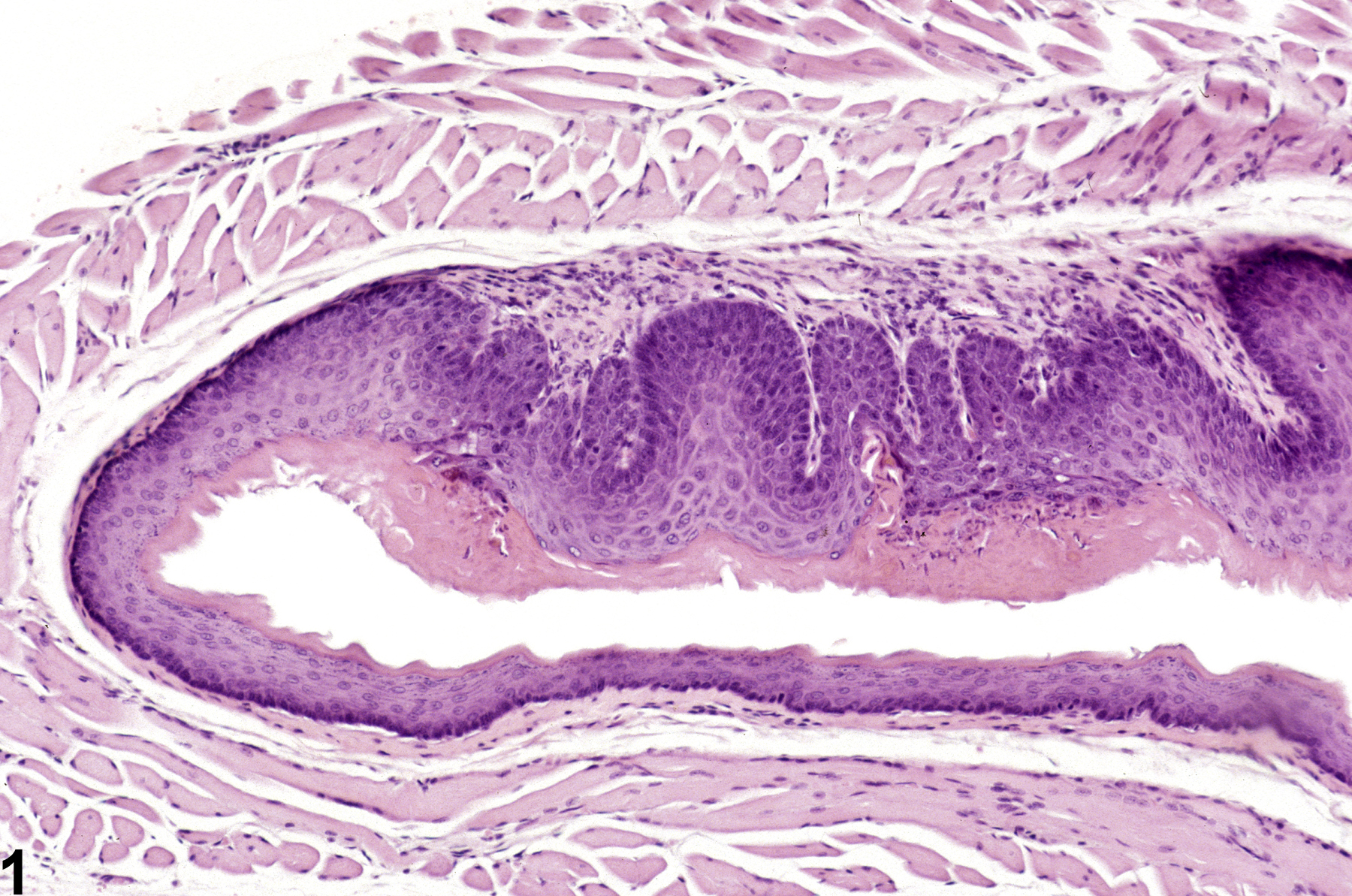

Esophagus, Epithelium - Hyperplasia in a female B6C3F1 mouse from a chronic study. There are rete peg-like structures and accompanying hyperkeratosis.