Alimentary System

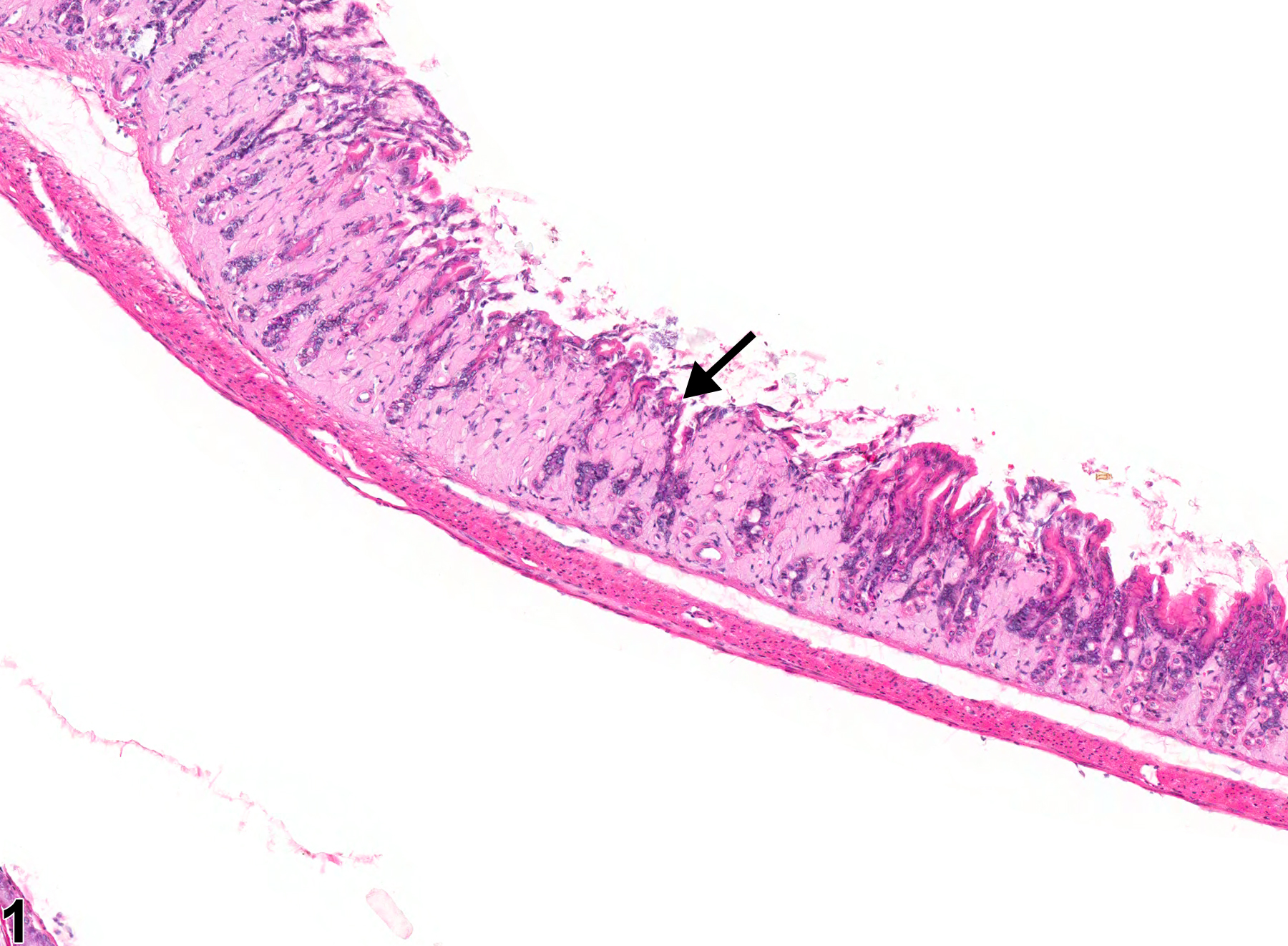

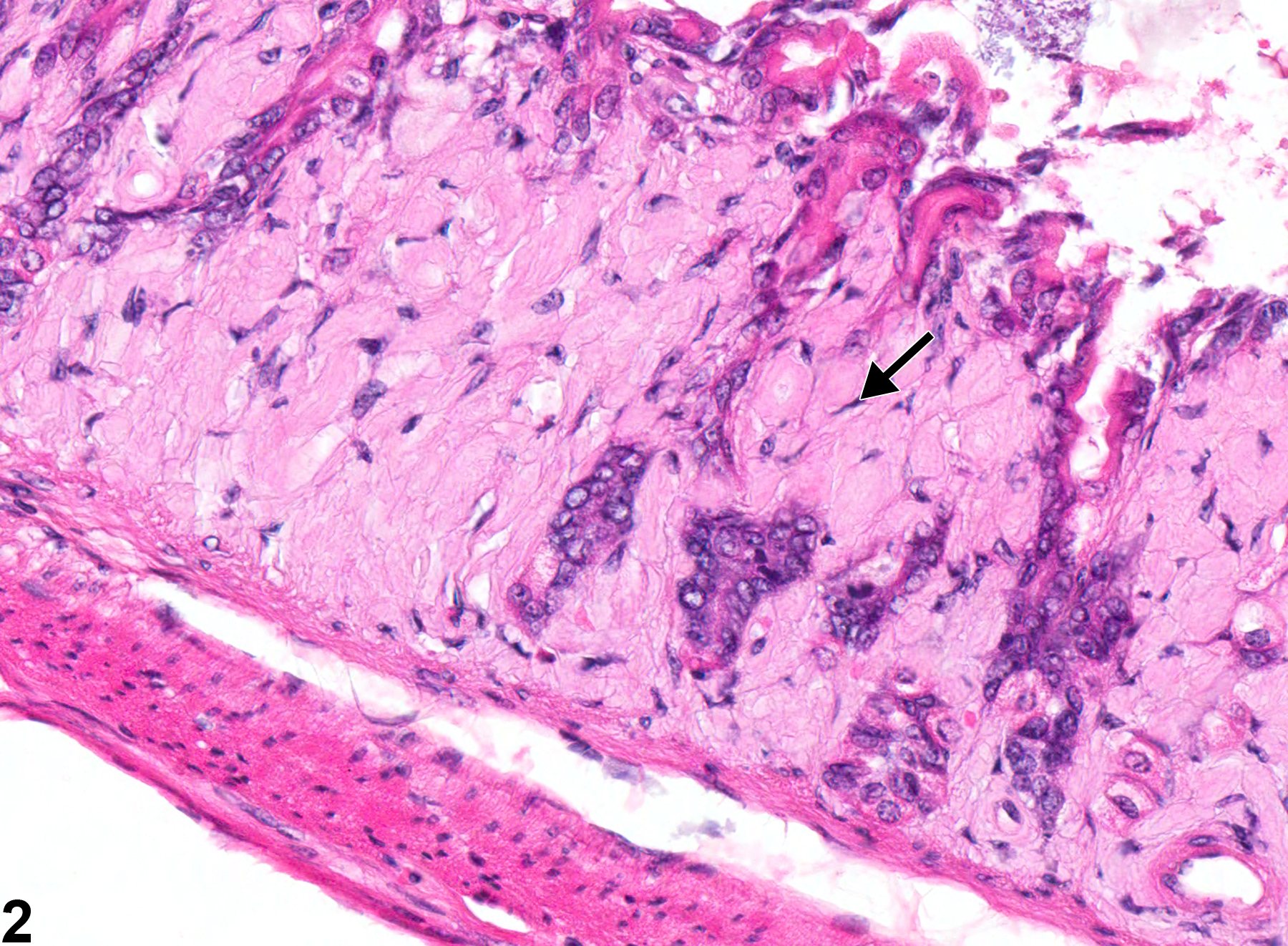

Stomach, Glandular Stomach - Amyloid

Narrative

Bucher JR, Shackelford CC, Haseman JK, Johnson JD, Kurtz PJ, Persing RL. 1994. Carcinogenicity studies of oxazepam in mice. Fundam Appl Toxicol 23:280-297.

Abstract: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272059084711067Engelhardt JA, Gries CL, Long GG. 1993. Incidence of spontaneous neoplastic and nonneoplastic lesions in Charles River CD-1 mice varies with the breeding origin. Toxicol Pathol 21:538-541.

Full Text: http://tpx.sagepub.com/content/21/6/538.full.pdfFrith CH, Chandra M. 1991. Incidence, distribution, and morphology of amyloidosis in Charles Rivers CD-1 mice. Toxicol Pathol 19:123-127.

Full Text: http://tpx.sagepub.com/content/19/2/123.full.pdfFrith CH, Goodman DG, Boysen BG. 2007. The mouse. In: Animal Models in Toxicology, 2nd ed (Gad SC, ed). CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 19-146.

Greaves P. 2007. Digestive system. In: Histopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies, 3rd ed. Academic Press, London, 334-456.

Myers RK, McGavin MD. 2007. Cellular and tissue responses to injury. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, 4th ed (McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds). Mosby, St Louis, MO, 3-62.

Percy DH, Barthold SW. 2001. Mouse. In: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, 2nd ed. Iowa State Press, Ames, 3-106.

Ward JM, Mann PC, Morishima H, Frith CH. 1999. Thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes. In: Pathology of the Mouse (Maronpot RR, ed). Cache River Press, St Louis, MO, 333-456.

Stomach, Glandular stomach - Amyloid in a female Swiss Webster mouse from a chronic study. Amyloid (arrow) is deposited in the lamina propria.