Alimentary System

Stomach, Glandular Stomach - Necrosis

Narrative

Brown HR, Hardisty JF. 1990. Oral cavity, esophagus and stomach. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat (Boorman GA, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 9-30.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/9002563Myers RK, McGavin MD. 2007. Cellular and tissue responses to injury. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, 4th ed (McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds). Mosby, St Louis, MO, 3-62.

National Toxicology Program. 1992. NTP TR-399. Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Titanocene Dichloride (CAS No. 1271-19-8) in F344/N Rats (Gavage Studies). NTP, Research Triangle Park, NC.

Abstract: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/12249

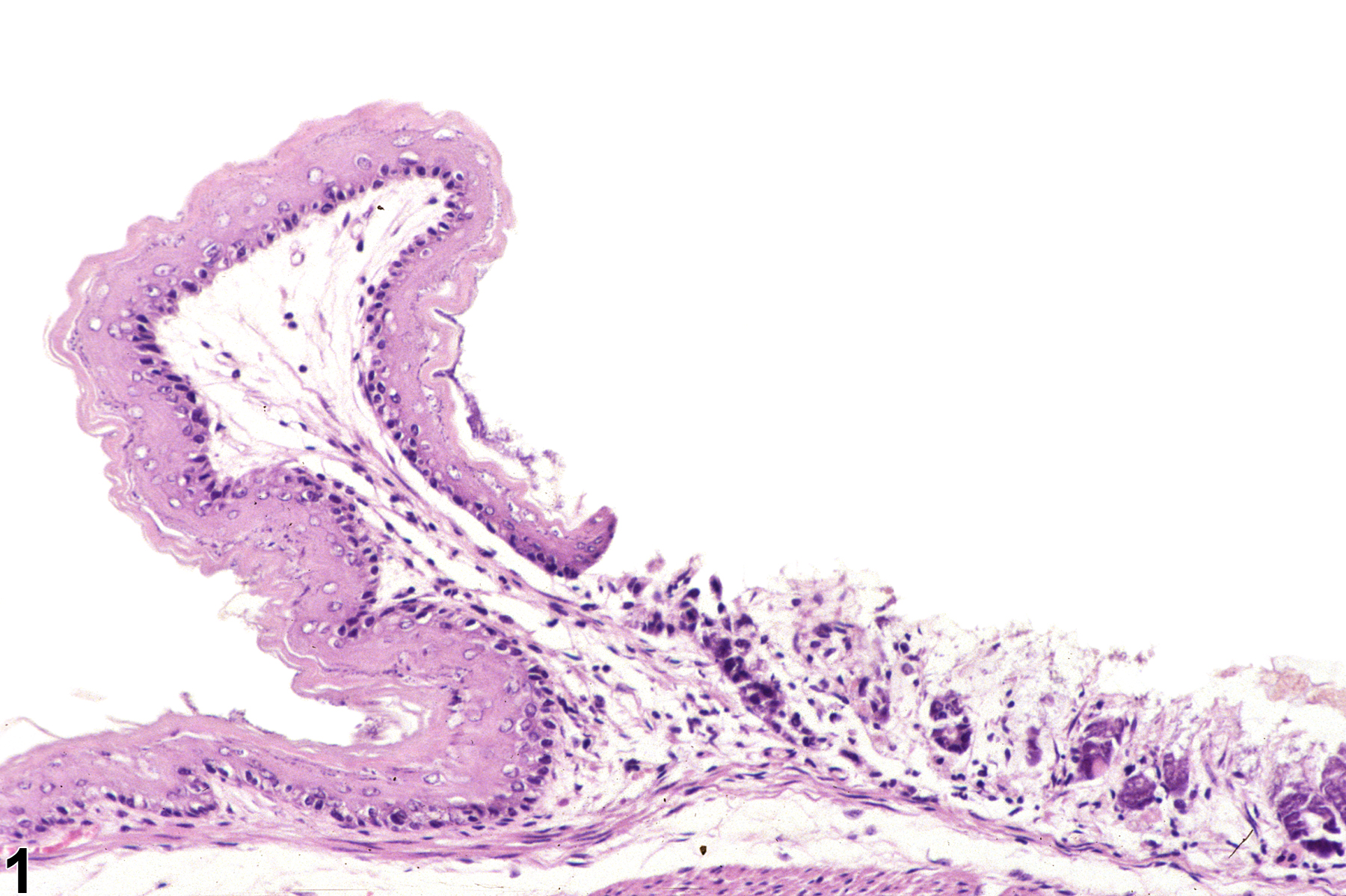

Stomach, Glandular stomach - Necrosis in a female B6C3F1 mouse from a subchronic study. There is loss of glandular epithelial cells within the mucosa.