Alimentary System

Oral Mucosa - Hyperplasia, Squamous

Narrative

Brown HR, Hardisty JF. 1990. Oral cavity, esophagus and stomach. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat (Boorman GA, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 9-30.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/9002563Leininger JR, Jokinen MP, Dangler CA, Whiteley LO. 1999. Oral cavity, esophagus, and stomach. In: Pathology of the Mouse (Maronpot RR, ed). Cache River Press, St Louis, MO, 29-48.

Yoshizawa K, Walker NJ, Jokinen MP, Brix AE, Sells DM, March T, Wyde ME, Orzech D, Haseman JK, Nyska A. 2004. Gingival carcinogenicity in female Harlan Sprague-Dawley rats following two-year oral treatment with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and dioxin-like compounds. Toxicol Sci 83:64-77.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15509667

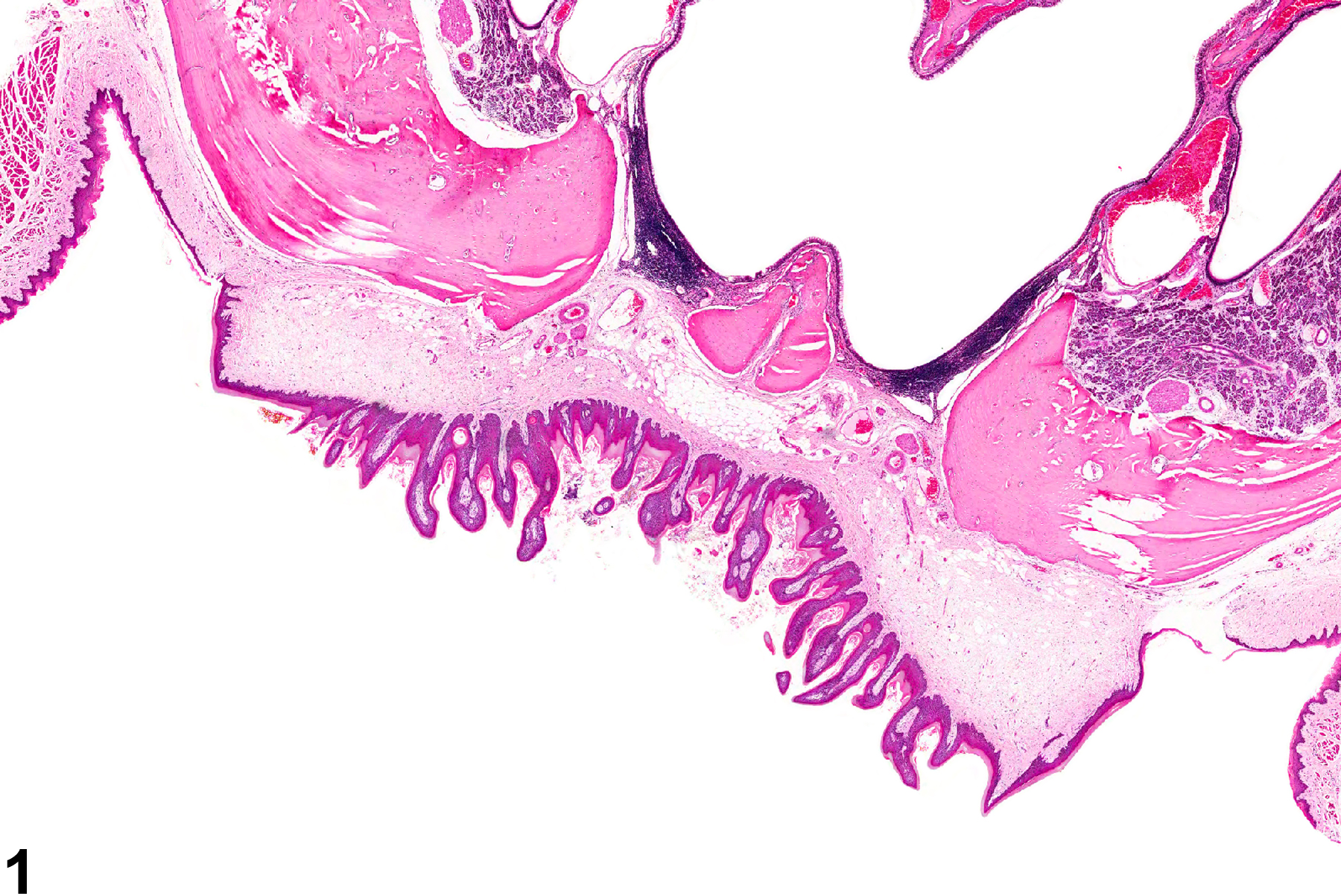

Oral mucosa - Hyperplasia, Squamous in a female F344/N rat from chronic study. There is hyperplasia of the squamous epithelium of the hard palate.