Alimentary System

Salivary Gland - Necrosis

Narrative

Botts S, Jokinen M, Gaillard ET, Elwell MR, Mann PC. 1999. Salivary, Harderian, and lacrimal glands. In: Pathology of the Mouse (Maronpot RR, ed). Cache River Press, St Louis, MO, 49-80.

Elmore S, Lanning L, Allison N, Vallant M, Nyska A. 2006. The transduction of rat submandibular glands by an adenoviral vector carrying the human growth hormone gene is associated with limited and reversible changes at the infusion site. Toxicol Pathol 34:385-392.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16844666Neuenschwander SB, Elwell MR. 1990. Salivary glands. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat (Boorman GA, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 31-42.

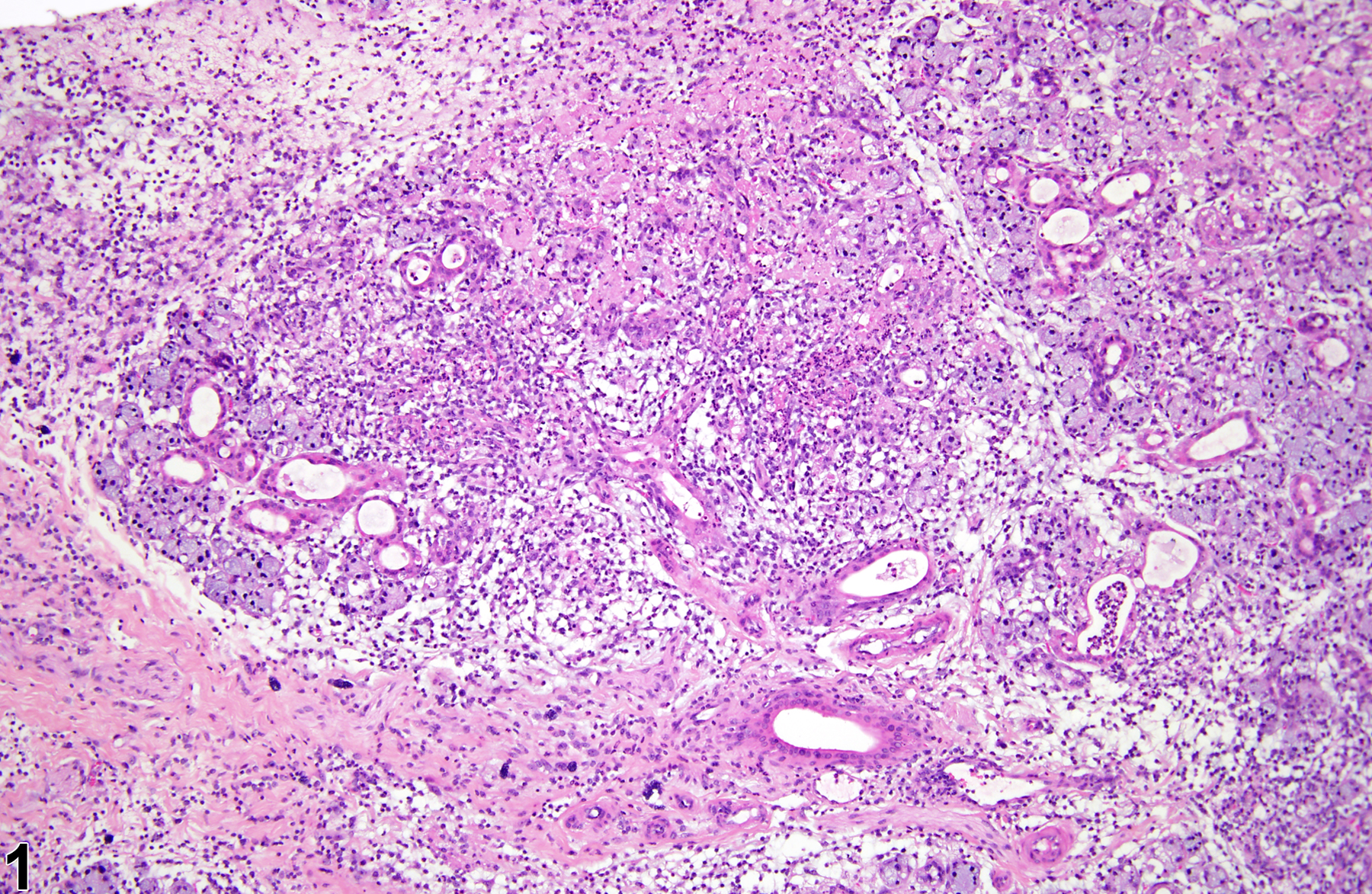

Salivary gland - Necrosis in a male F344/N rat from a subchronic study. There is necrosis of the acinar cells (arrow) with inflammation.