Alimentary System

Tooth - Inflammation

Narrative

Inflammation of the tooth can involve the pulp, the cementum, the dentin, or any combination of these and can extend to the periodontal tissues. Chronic tooth inflammation can result in tooth resorption. Tooth inflammation is most often caused by bacteria but can be the result of foreign bodies in the oral cavity. If a bacterial infection gains access to the dentin tubules, it can spread throughout the dentin and into the tooth pulp. Because of its enclosure within the dentin, swelling of the tooth pulp due to inflammation can result in increased intrapulpal pressure, decreased blood flow, and ischemia. Caries is a gross term for inflammation of the calcified portions of the tooth. Dental caries are not common in mice or rats, but high levels of carbohydrates (e.g., sucrose or xylitol) in the diet can induce their formation. Tooth inflammation can be a background finding in animals with dental injury.

Betton GR. 1998. The digestive system I: The gastrointestinal tract and exocrine pancreas. In: Target Organ Pathology (Turton J, Hooson J, eds). Taylor and Francis, London, 29-60.

Brown HR, Hardisty JF. 1990. Oral cavity, esophagus and stomach. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat (Boorman GA, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 9-30.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/9002563Long PH, Leininger JR. 1999. Teeth. In: Pathology of the Mouse (Maronpot RR, ed). Cache River Press, St Louis, MO, 13-28.

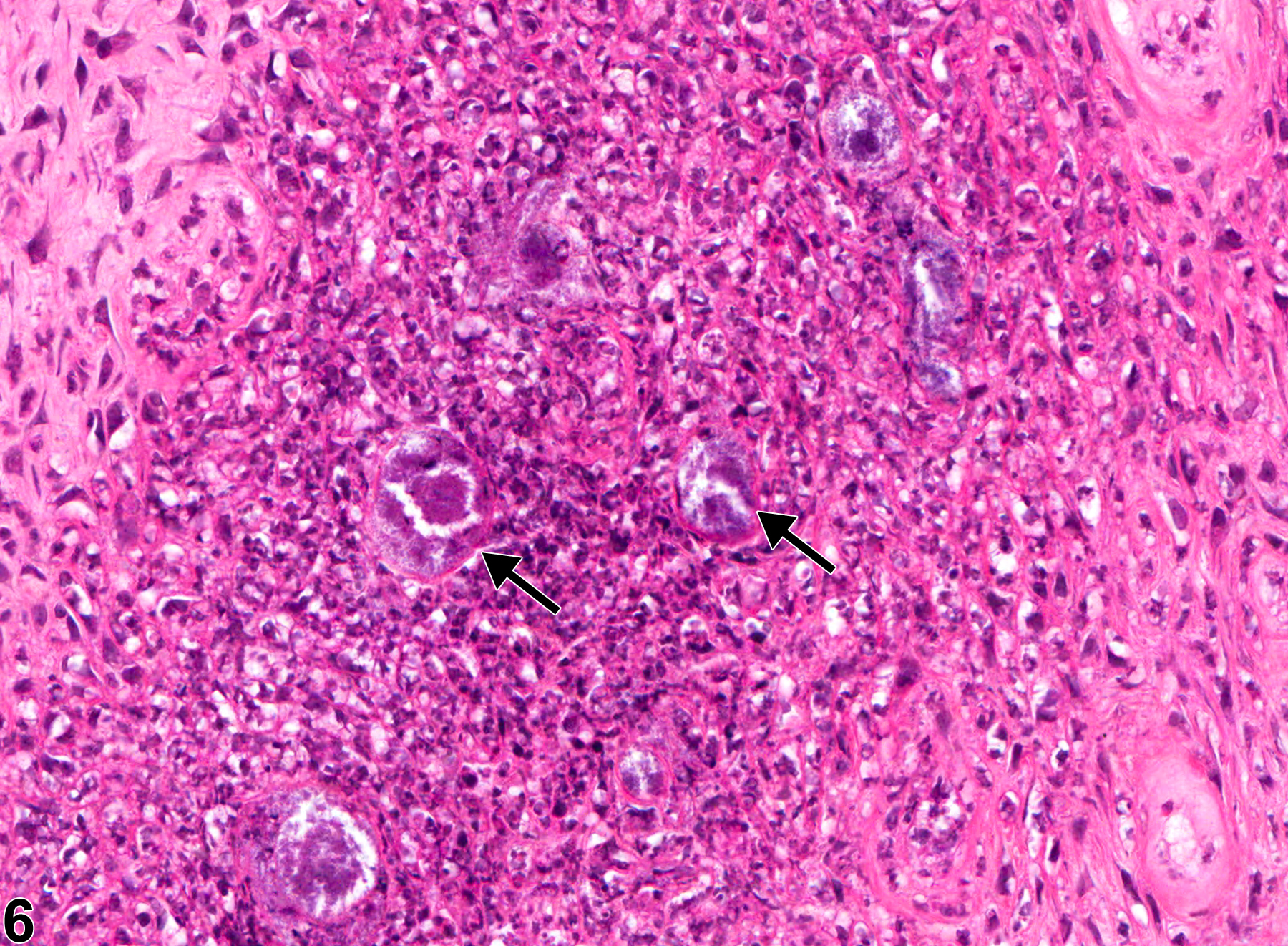

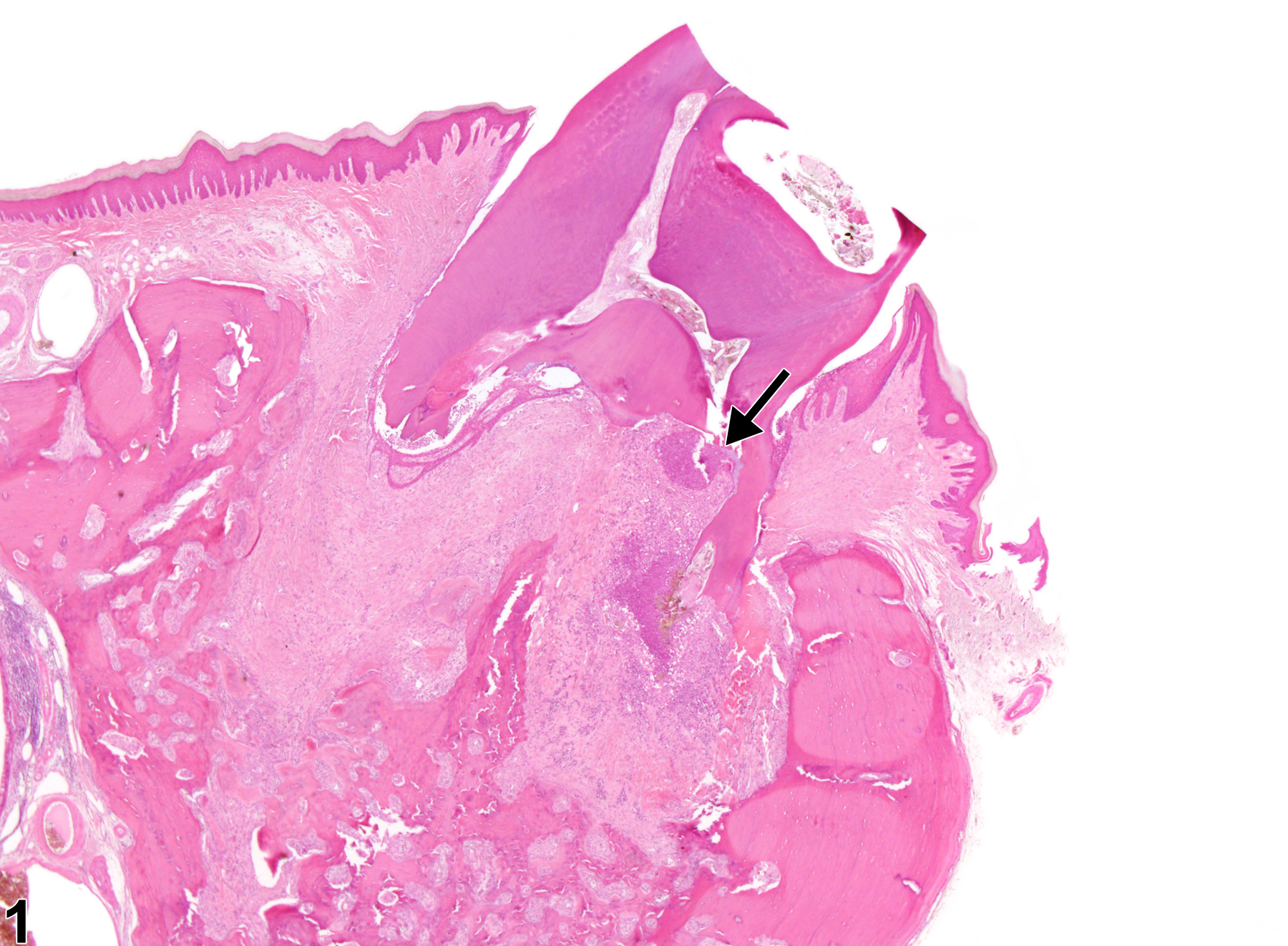

Tooth - Inflammation, Chronic active in a male Harlan Sprague-Dawley rat from a chronic study. Cementum and dentin of the root are being resorbed because of chronic active inflammation (arrow).