Cardiovascular System

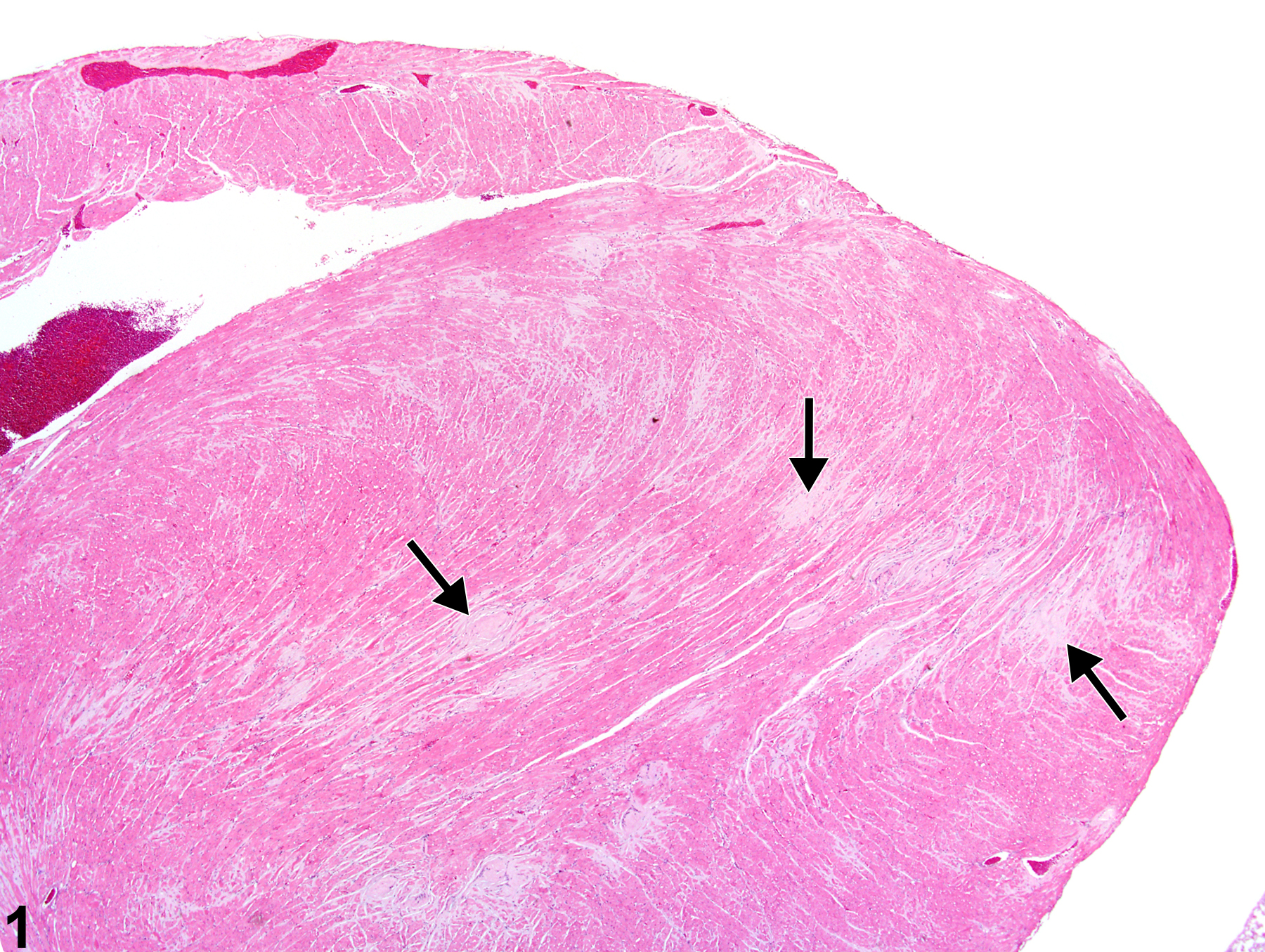

Heart - Amyloid

Narrative

Bucher JR, Shackelford CC, Hasemen JK, Johnson JD, Kurtz PJ, Persing RL. 1994. Carcinogenicity studies of oxazepam in mice. Fund Appl Toxicol 23:280-297.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7982536Elwell MR, Mahler JF. 1999. Heart, blood vessels, and lymphatic vessels. In: Pathology of the Mouse: Reference and Atlas (Maronpot RR, Boorman GA, Gaul BW, eds). Cache River Press, Vienna, IL, 361-380.

Gruys E, Tooten PC, Kuijpers MH. 1996. Lung, ileum and heart are predilection sites for AApoAII amyloid deposition in CD-1 Swiss mice used for toxicity studies. Pulmonary amyloid indicates AApoAII. Lab Anim 30:28-34.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8709570Maita K, Hirano M, Harada T, Mitsumori K, Yoshida A, Takahashi K, Nakashima N, Kitazawa T, Enomoto A, Inui K, Shirasu Y. 1988. Mortality, major cause of moribundity, and spontaneous tumors in CD-1 mice. Toxicol Pathol 16:340-349.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3194656Yoshizawa K, Kissling GE, Johnson JA, Clayton NP, Flagler ND, Nyska A. 2005. Chemical-induced atrial thrombosis in NTP rodent studies: Potential mechanisms and literature review. Toxicol Pathol 33:517-532.

Full Text: http://tpx.sagepub.com/content/33/5/517.full

Heart - Amyloid in a male Swiss Webster mouse from a chronic study. Multiple amyloid plaques (arrows) are present in the myocardium.