Cardiovascular System

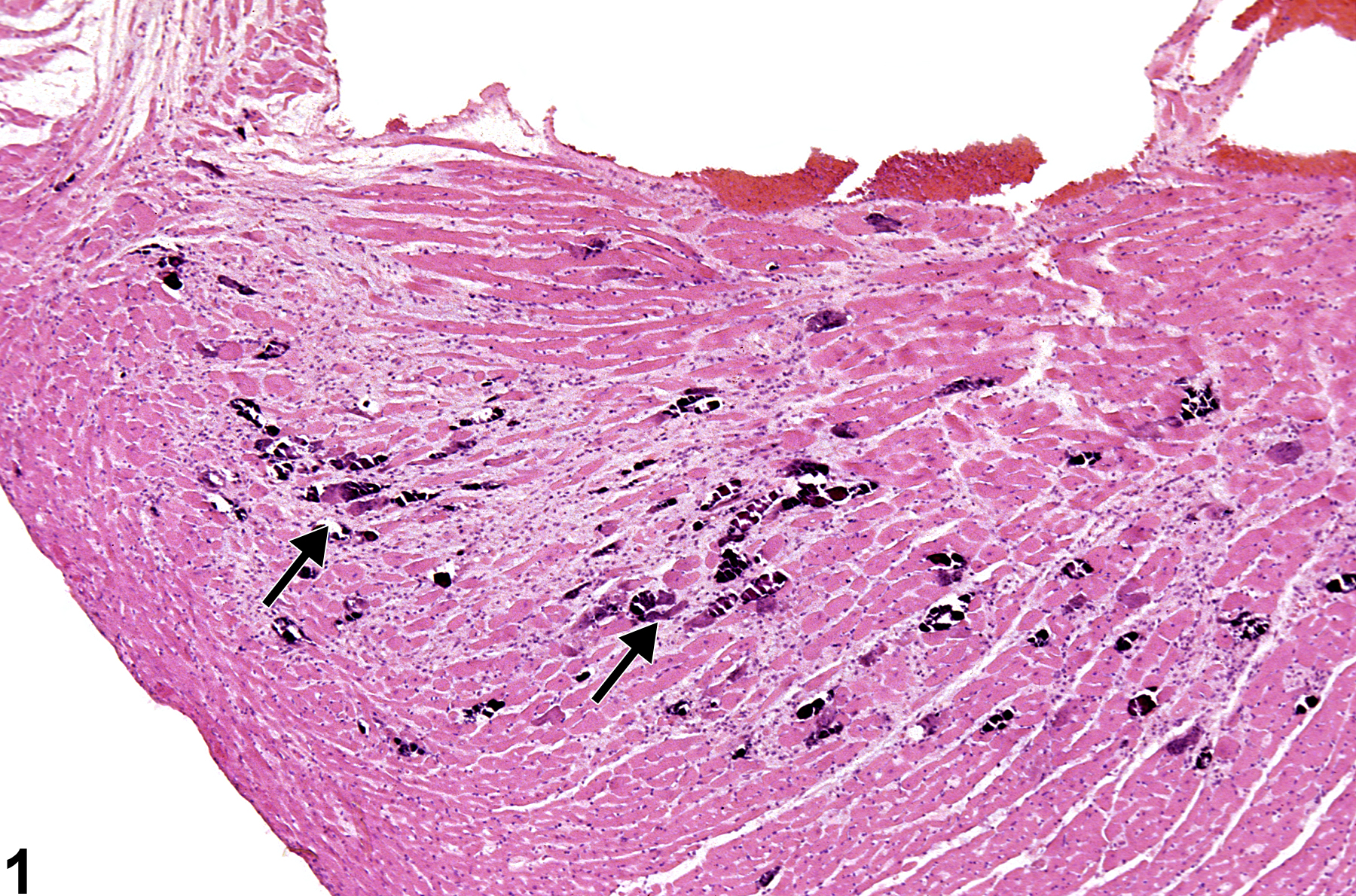

Heart - Mineral

Narrative

BALB/c mice develop epicardial mineralization, predominantly of the right ventricle. C3H mice develop myocardial mineralization of both ventricles. DBA mice may develop epicardial and myocardial mineralization.

Jokinen MP, Boyle M, Lieuallen WG, Johnson CL, Malarkey DE, Nyska A. 2011. Morphologic aspects of rodent cardiotoxicity in a retrospective evaluation of National Toxicology Program studies. Toxicol Pathol 39(5):850-860.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21747121

Heart - Mineral in a male F344/N rat from a chronic study. Dark blue crystalline material is present in the myocardium (arrows).