Reproductive System, Female

Uterus - Inflammation

Narrative

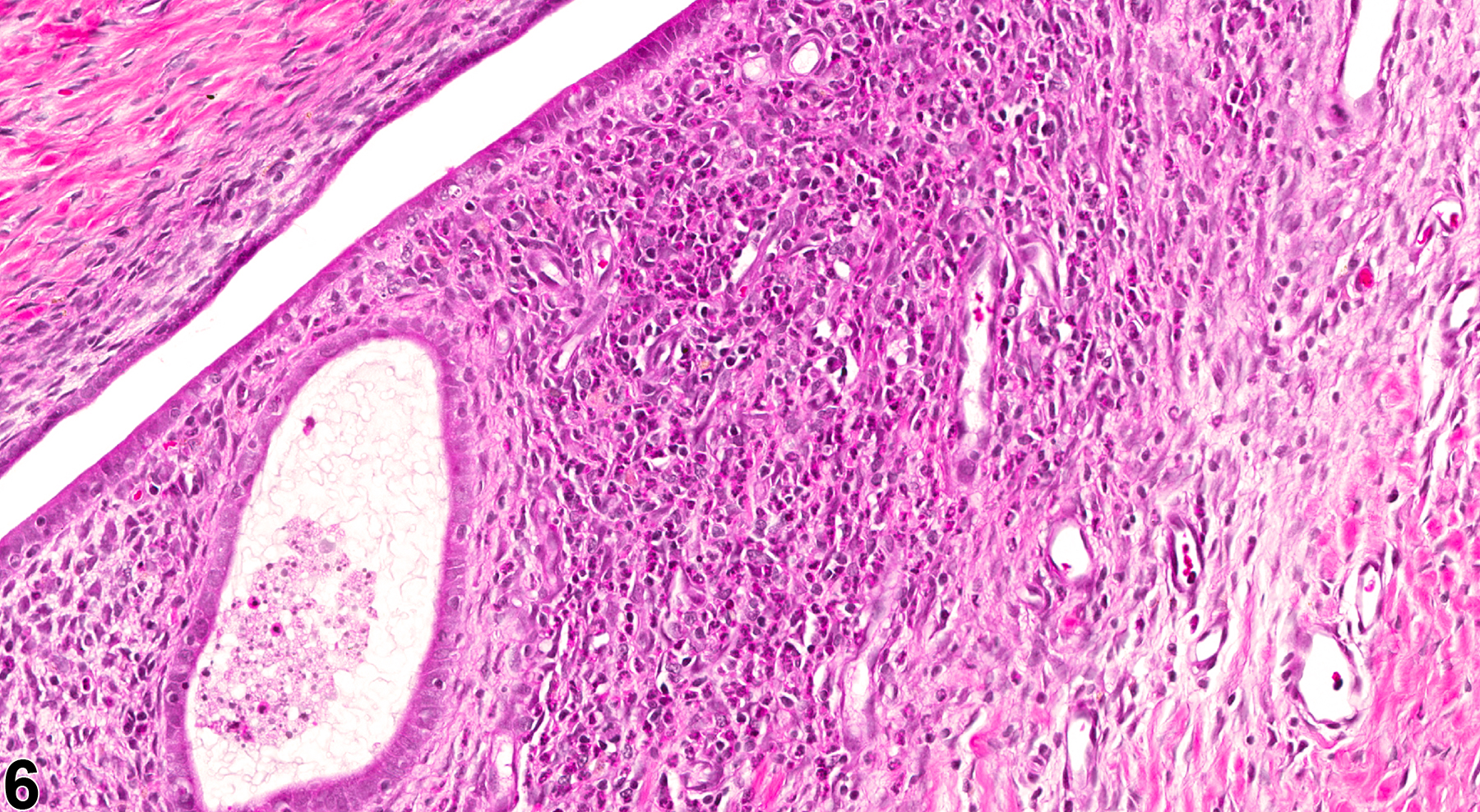

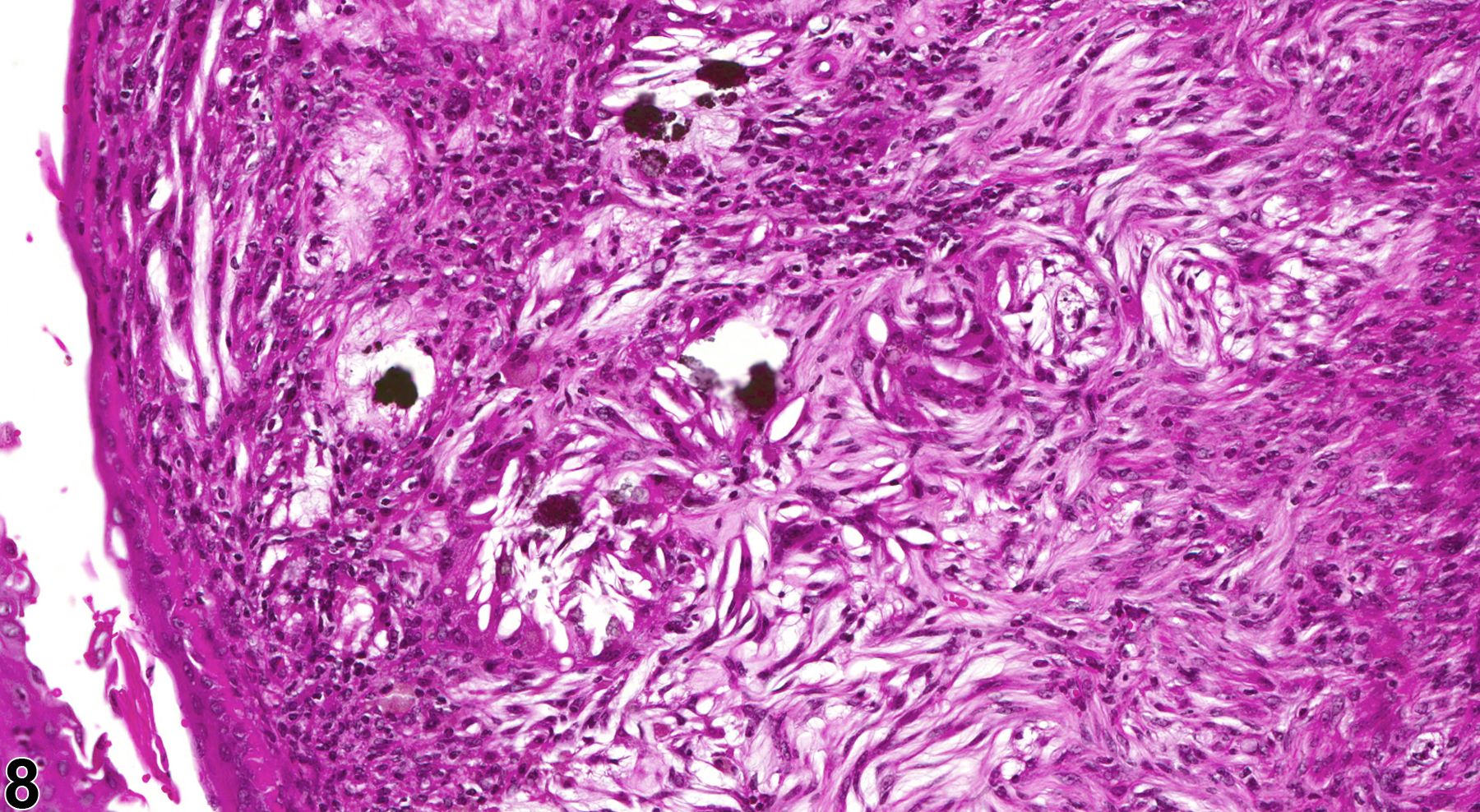

In NTP studies, there are five standard categories of inflammation: acute, suppurative, chronic, chronic active, and granulomatous. In acute inflammation, the predominant infiltrating cell is the neutrophil, though fewer macrophages and lymphocytes may also be present. There may also be evidence of edema or hyperemia. The neutrophil is also the predominant infiltrating cell type in suppurative inflammation (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4), but they are aggregated, and many of them are degenerate (suppurative exudate). Cell debris, both from the resident cell populations and from infiltrating leukocytes, and proteinaceous fluid containing fibrin, fewer macrophages, occasional lymphocytes or plasma cells, and, possibly, an infectious agent may also be present in within the exudate. Grossly, these lesions would be characterized by the presence of pus. The tissue surrounding the exudate may contain fibroblasts, fibrous connective tissue, and mixed inflammatory cells, depending on the chronicity of the lesion. Abscesses should be diagnosed histologically as suppurative inflammation. Lymphocytes predominate in chronic inflammation. Lymphocytes also predominate in chronic active inflammation (Figure 5 and Figure 6), but there are also a significant number of neutrophils. Both lesions may contain macrophages. Granulomatous inflammation (Figure 7 and Figure 8) is another form of chronic inflammation, but this diagnosis requires the presence of a significant number of aggregated, large, activated macrophages, epithelioid macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells.

Inflammation is differentiated from cellular infiltrates by the presence of other changes, such as edema, hemorrhage, degeneration, necrosis, or other evidence of tissue damage. Severe diffuse suppurative inflammation (pyometra) is rarely seen. Chronic uterine inflammation can induce squamous metaplasia of superficial and glandular epithelia, which must be differentiated from squamous metaplasia that occurs due to estrogen dominance. Uterine inflammation may accompany other uterine changes – uterus endometrium hyperplasia, adenomyosis, neoplasia, and so forth. Uterus inflammation must be distinguished from the normal presence of inflammatory cells, especially transmigratory neutrophils/eosinophils/endometrial lymphocytes (which are lobulated) in the endometrium at certain stages of the estrous cycle. Uterus inflammation must be distinguished from histiocytic sarcoma and lymphoma. Inflammatory changes generally have a mixed population of cells, in contrast to neoplasms, and there are usually other signs of inflammation, such as hemorrhage, edema, and tissue destruction. Lymphoma and histiocytic sarcoma are usually multicentric and composed of monomorphic cell populations. The diagnosis of inflammation of the endometrium should be reserved for lesions where significant epithelial and stromal inflammatory changes are present.

Uterus - Inflammation should be diagnosed and graded. Secondary lesions such as necrosis, epithelial hyperplasia, ulcer, and fibrosis should not be diagnosed separately unless warranted by severity but should be described in the pathology narrative. If the inflammation is secondary to another lesion, such as ulcer or necrosis, it should not be diagnosed separately unless warranted by severity but should be described in the narrative as a component of the primary lesion. Pyometra should be diagnosed as Uterus - Inflammation, Suppurative.

Davis BJ, Dixon D, Herbert RA. 1999. Ovary, oviduct, uterus, cervix and vagina. In: Pathology of the Mouse: Reference and Atlas (Maronpot RR, Boorman GA, Gaul BW, eds). Cache River Press, Vienna, IL, 409-444.

Faccini JM, Abbott DP, Paulus GJJ. 1990. Female genital tract. In: Mouse Histopathology: A Glossary for Use in Toxicity and Carcinogenicity Studies (Greaves P, Faccini JM, eds). Elsevier, Amsterdam, 147–168.

Greaves P. 2012. Female genital tract. In: Histopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies: Interpretation and Relevance in Drug Safety Evaluation, 4th ed. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 667-724.

Leininger JR, Jokinen MP. 1990. Oviduct, uterus and vagina. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat (Boorman GA, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 443-459.

Maekawa A, Maita K. 1996. Changes in the uterus and vagina. In: Pathobiology of the Aging Mouse (Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Capen CC, Carlton WW, Sundberg JP, Ward JM, eds). ILSI Press, Washington, DC, 469-480.

National Toxicology Program. 1990. NTP TR-381. Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of d-Carvone (CAS No. 2244-16-8) in B6C3F1 Mice (Gavage Studies). NTP, Research Triangle Park, NC.

Abstract: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/11301National Toxicology Program. 1992. NTP TR-406. Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of γ-Butyrolactone (CAS No. 96-48-0) in F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Gavage Studies). NTP, Research Triangle Park, NC.

Abstract: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/7692

Uterus - Inflammation, Suppurative in a female B6C3F1/N mouse from a chronic study. An area of suppurative inflammation is present in the myometrium, with many degenerating neutrophils.