Hematopoietic System

Bone Marrow - Necrosis

Narrative

There are several known causes of bone marrow necrosis. It may occur as a direct result of compound administration (e.g.,cyclophosphamide) or may be secondary to severe infectious disease states (e.g., septicemia) or tissue ischemia caused by vascular injury, thrombosis, or vascular occlusion. Specific causes of the latter include neoplasia (e.g., tumor emboli, vascular occlusion), disseminated intravascular coagulation (thrombosis), and exposure to endotoxin (vascular injury). Necrosis caused by an obstruction of the blood supply (infarct) generally has well-delineated borders microscopically as a distinguishing feature (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

In a rat study to evaluate the effects of feed restriction on common toxicologic parameters, severe diet restriction (75% reduction) of only two weeks resulted in bone marrow necrosis and degeneration. Specific observations included vacuolated or necrotic-appearing stromal cells, necrosis of hematopoietic cells, remaining hematopoietic tissue <25% of concurrent controls, focal areas of hemorrhage, and readily observed emperipolesis of neutrophils within the megakaryocytes.

Bain BJ, Clark DM, Lampert IA, Wilkins BS. 2001. Bone Marrow Pathology, 3rd ed. Blackwell, Ames, IA, 90-140.

Abstract: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/book/10.1002/9780470757130Levin S, Semler D, Ruben Z. 1993. Effects of two weeks of feed restriction on some common toxicologic parameters in Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Pathol 21:1-14.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8378702MacKenzie WF, Eustis SL. 1990. Bone marrow. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat: Reference and Atlas (Boorman GA, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, Mackenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, 315-337.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/9002563Rebar AH. 1993. General responses of the bone marrow to injury. Toxicol Pathol 21:118-129.

Full Text: http://tpx.sagepub.com/content/21/2/118.full.pdfTravlos GS. 2006. Histopathology of the bone marrow. Toxicol Pathol 34:566-598.

Abstract: http://tpx.sagepub.com/content/34/5/566.abstractWeiss DJ. 2010. Myelonecrosis and acute inflammation. In: Schalm’s Veterinary Hematology, 5th ed (Weiss DJ, Wardrop KJ, eds). Wiley-Blackwell, Ames, IA, 106-111.

Abstract: http://vet.sagepub.com/content/40/2/223.1

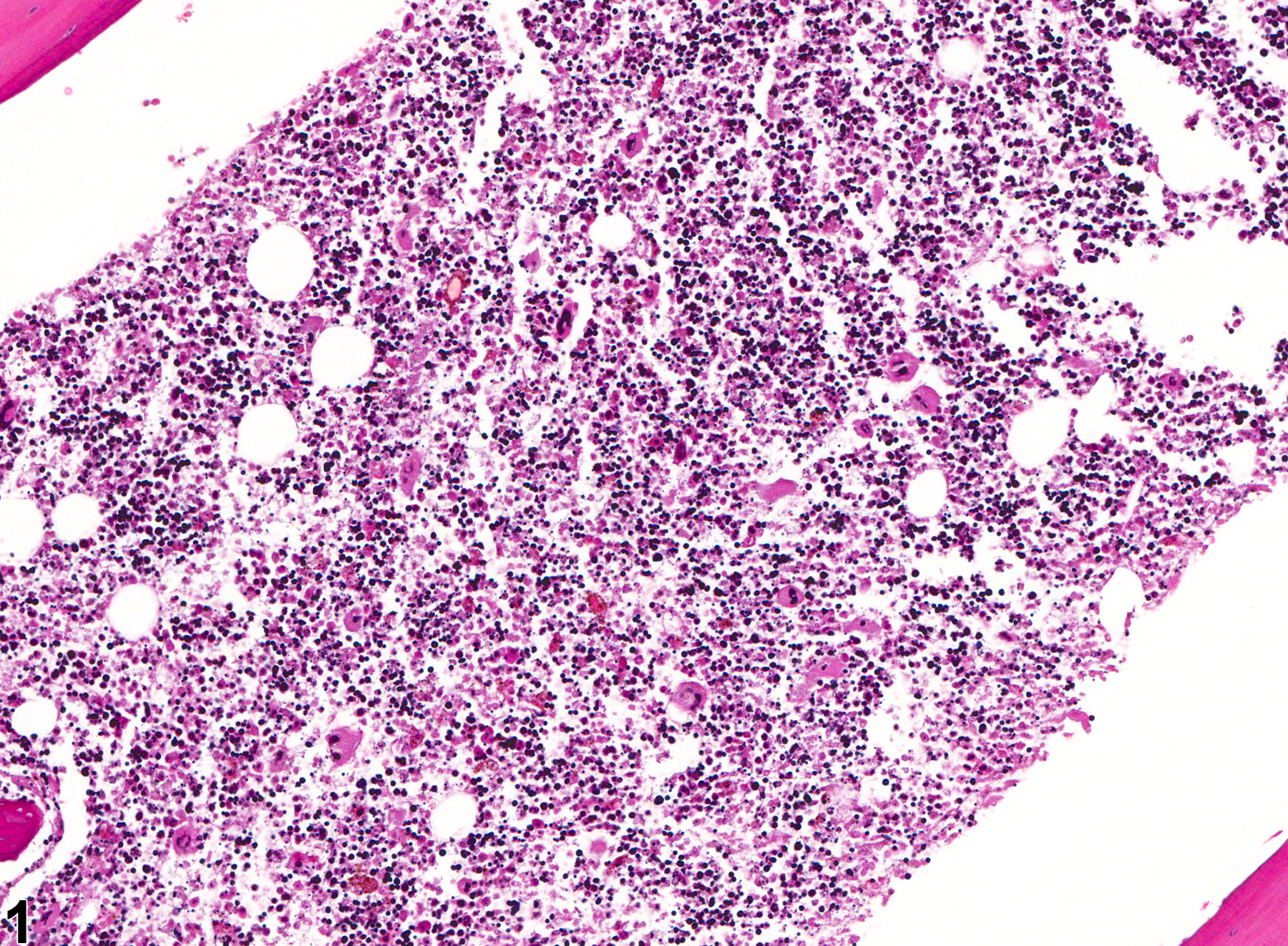

Bone marrow necrosis in a female B6C3F1 mouse from a chronic study (low magnification).