Integumentary System

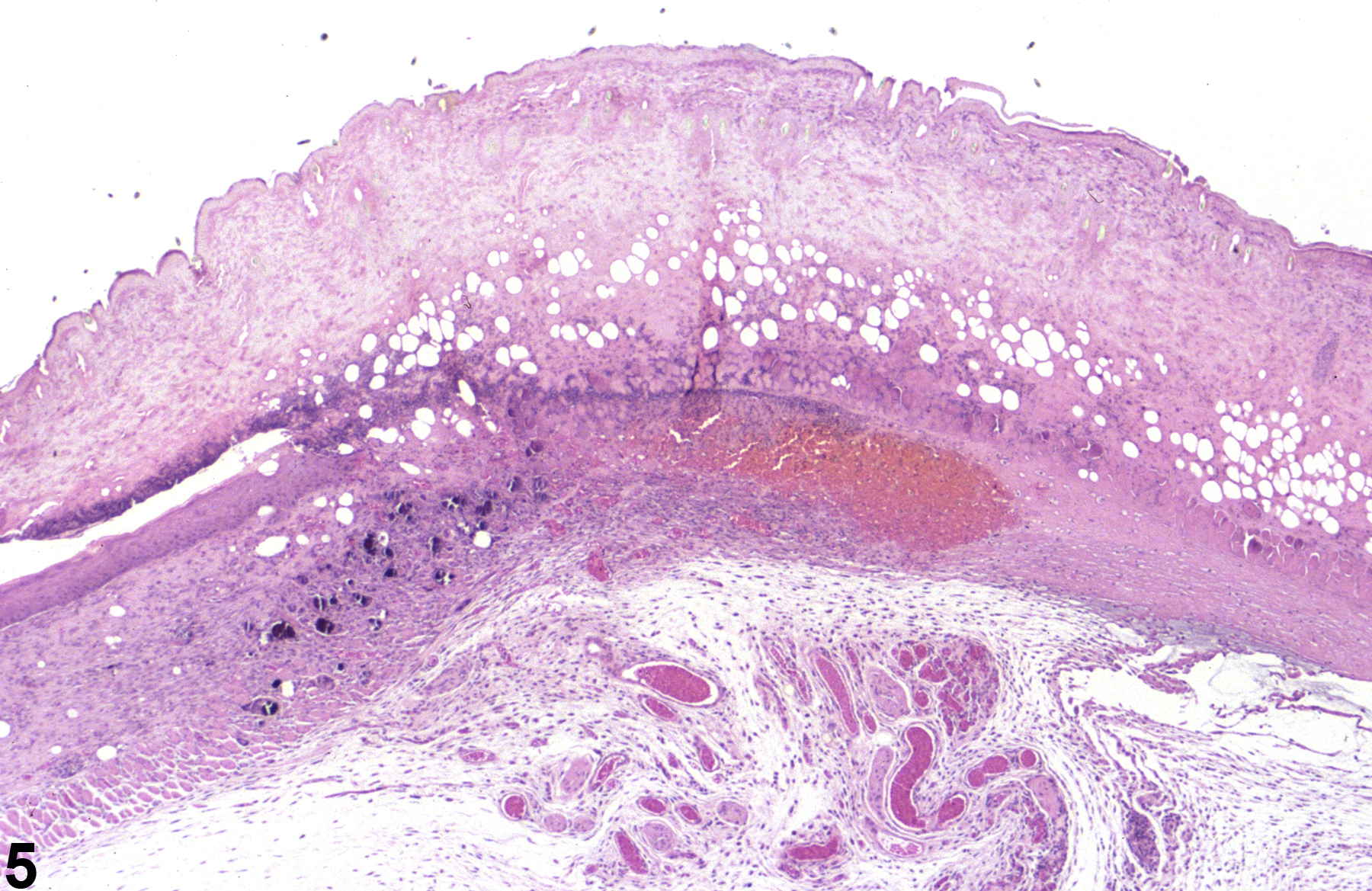

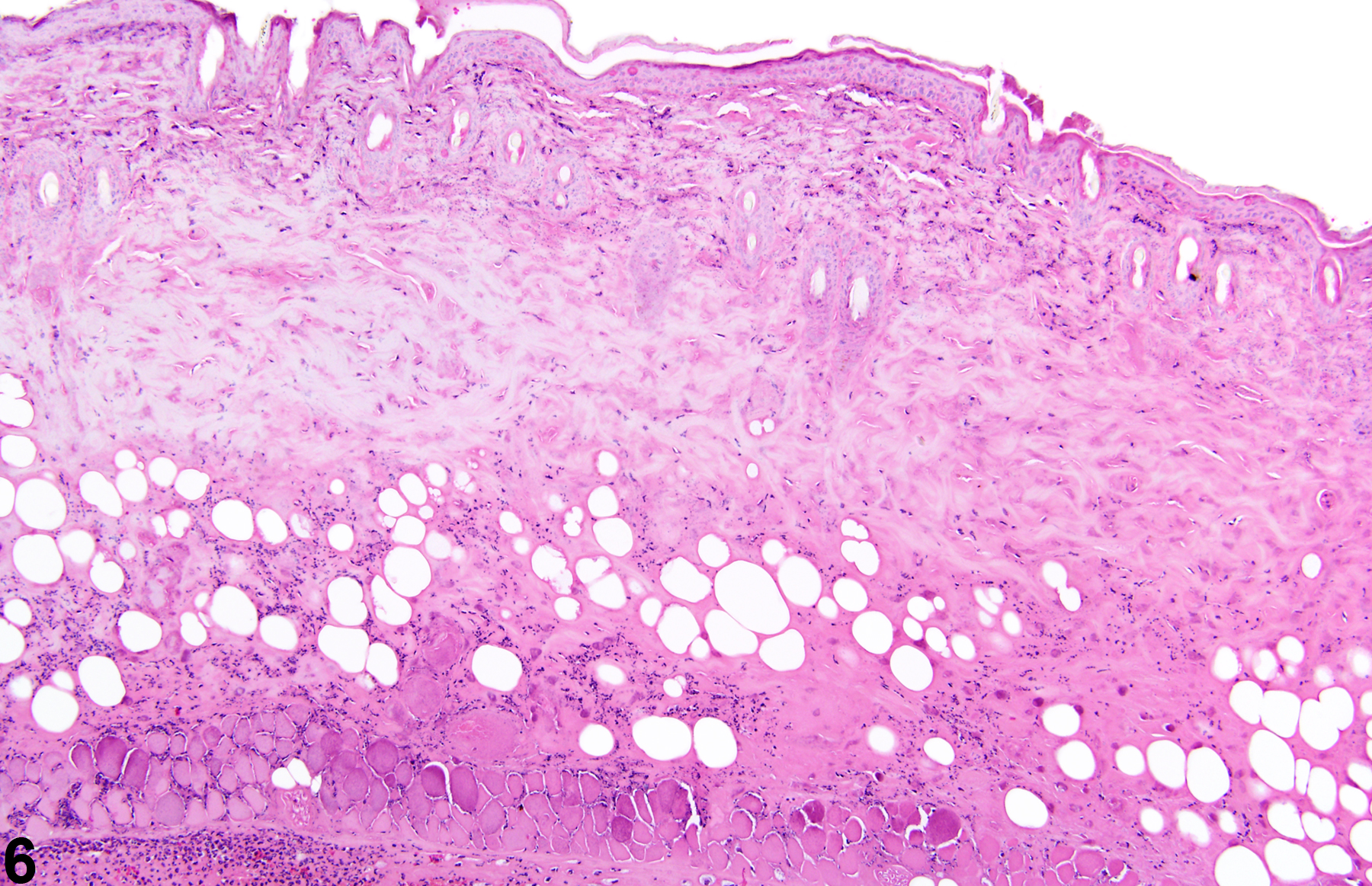

Skin - Necrosis

Narrative

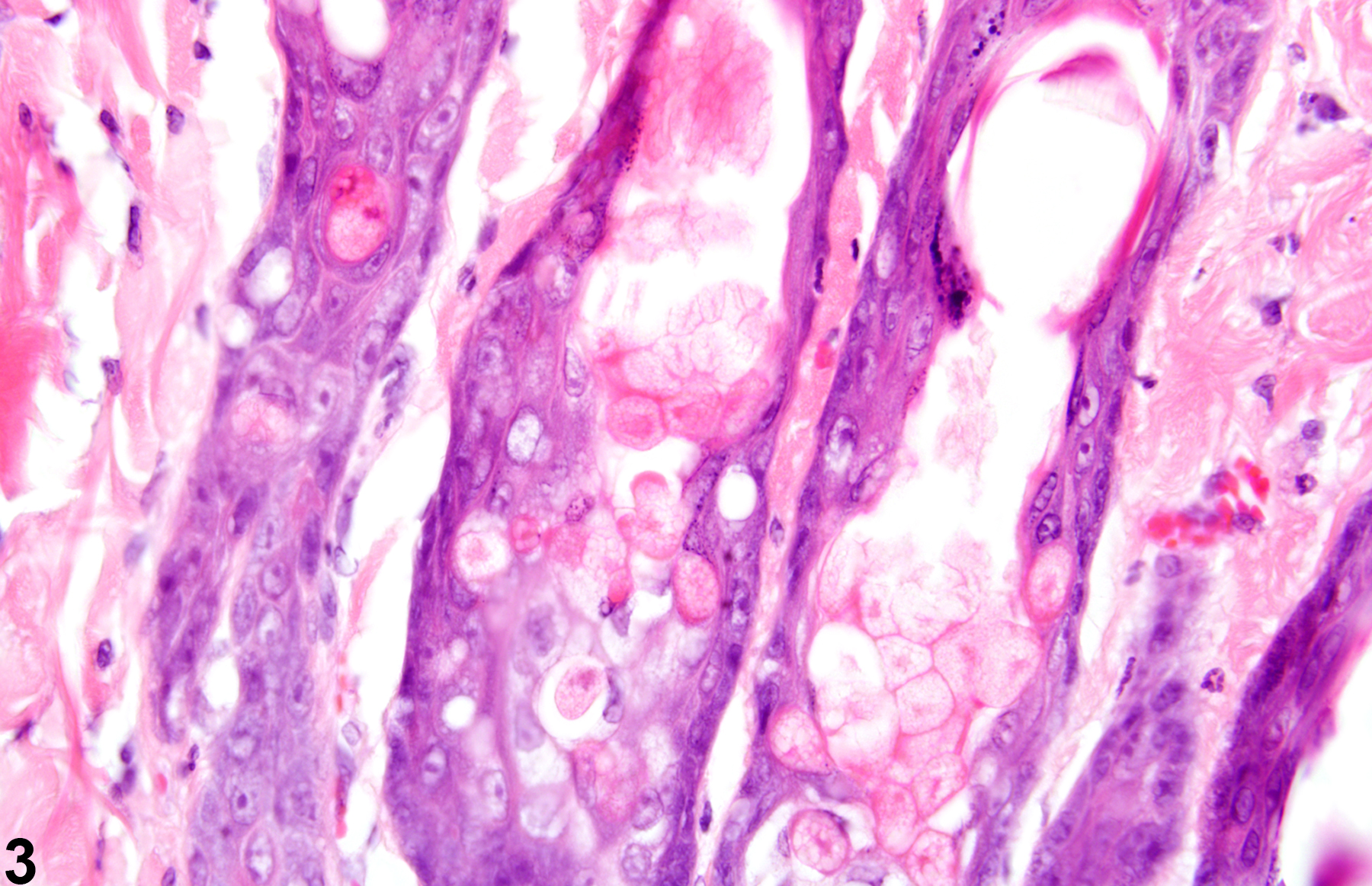

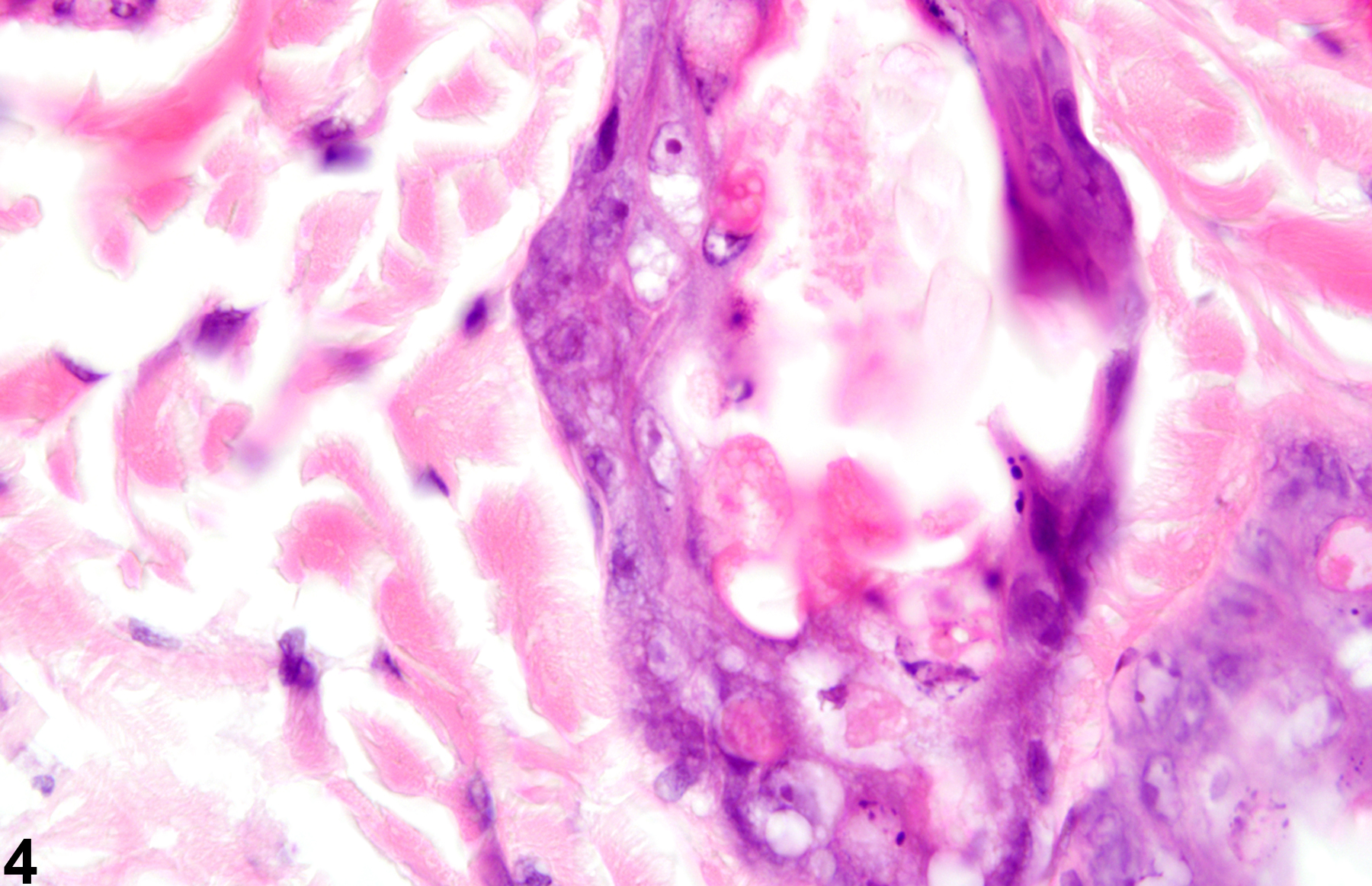

Skin necrosis (Figure 5 and Figure 6) is characterized by transmural necrosis affecting the epidermis, dermis, and possibly the subcutis. It is infrequently diagnosed as a primary lesion. Necrosis most commonly occurs secondary to damage of the epidermis and frequently extends into the dermis and subcutis. Necrosis extending into the subcutis is not to be confused with fat necrosis, which is limited to the subcutis and occurs sporadically as a background lesion in the subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen in mice and rats. Dystrophic mineralization is commonly seen as a component of skin necrosis. Metastatic mineralization is not associated with necrosis or inflammation but due to calcium:phosphorus imbalance.

Whenever present, the incidence of skin necrosis should be documented and assigned a severity grade. Dystrophic mineralization need not be diagnosed separately but should be described in the pathology narrative. Metastatic mineralization should be diagnosed whenever present, assigned a severity grade, and described in the pathology narrative. Fat necrosis (i.e., limited to the subcutis) should be diagnosed, graded, and described as a sporadic background finding in the narrative as “Skin, Subcutis – Necrosis.”

Elwell MR, Stedman MA, Kovatch RM. 1990. Skin and subcutis. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat: Reference and Atlas (Boorman GA, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, 261-277.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/9002563Klein-Szanto AJP, Conti CJ. 2002. Skin and oral mucosa. In: Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, 2nd ed (Haschek WM, Rousseaux CG, Wallig MA, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, 2:85-116.

Abstract: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780123302151Peckham JC, Heider K. 1999. Skin and subcutis. In: Pathology of the Mouse: Reference and Atlas (Maronpot RR, Boorman GA, Gaul BW, eds). Cache River Press, Vienna, IL, 555-612.

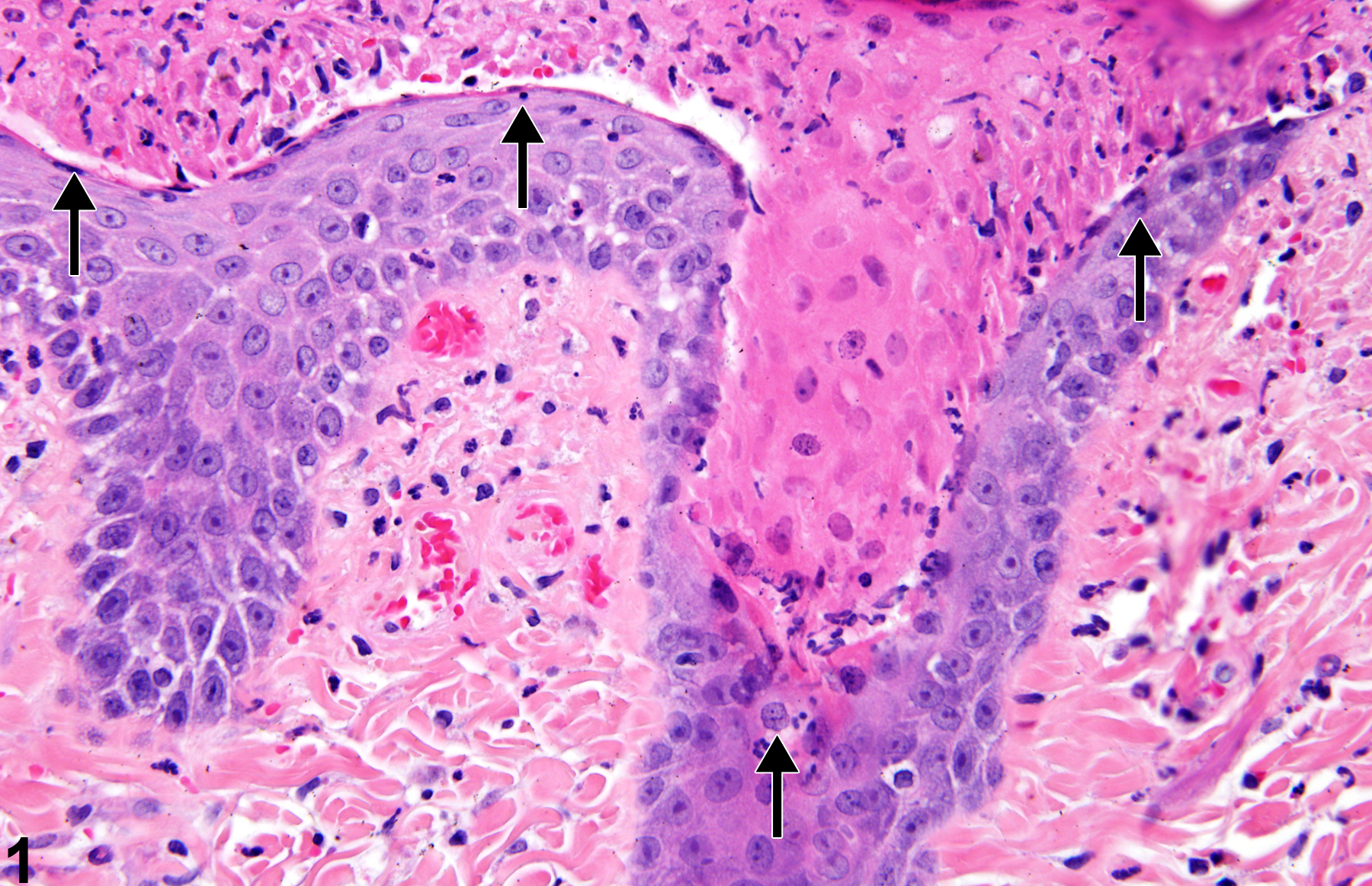

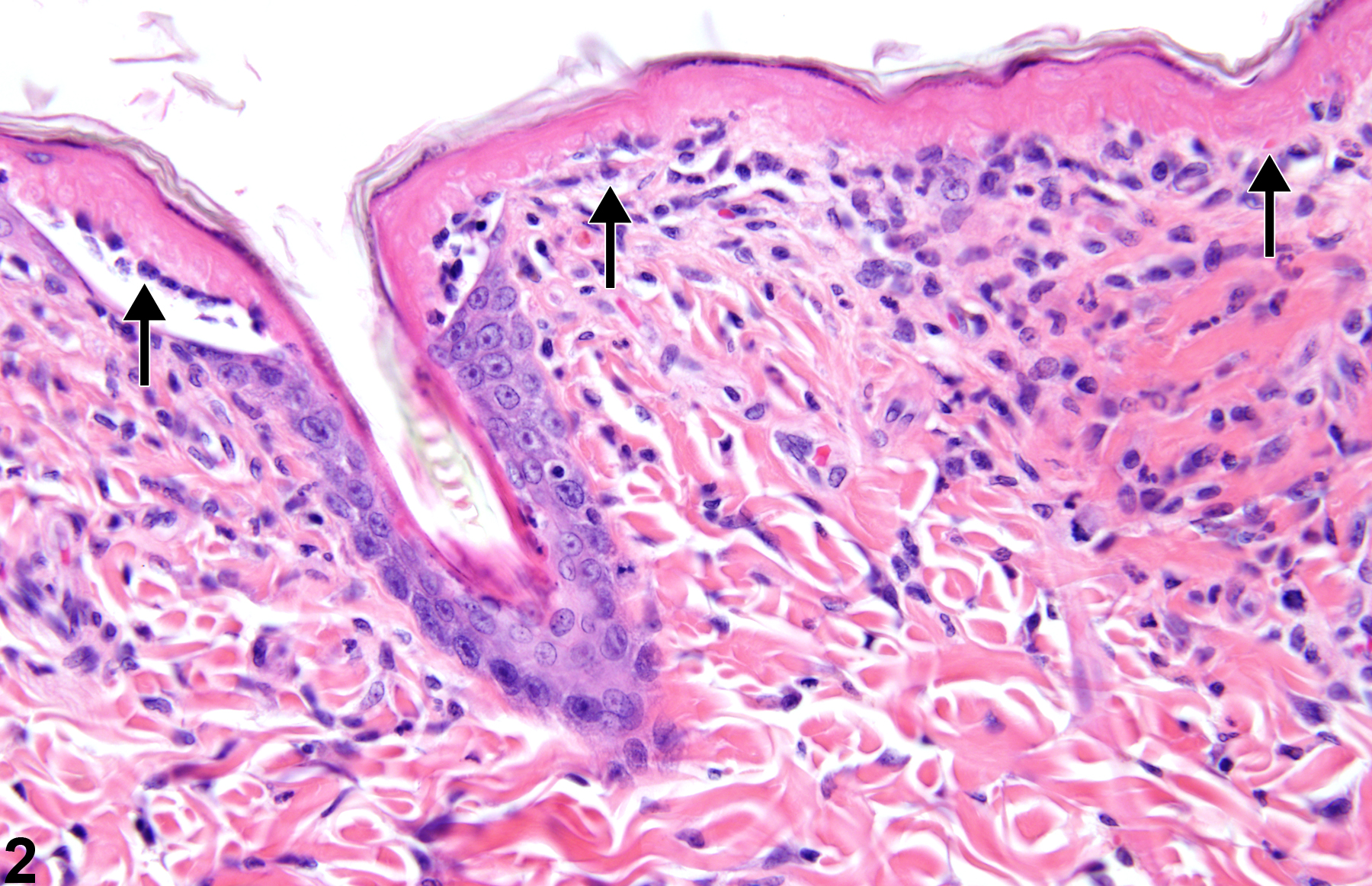

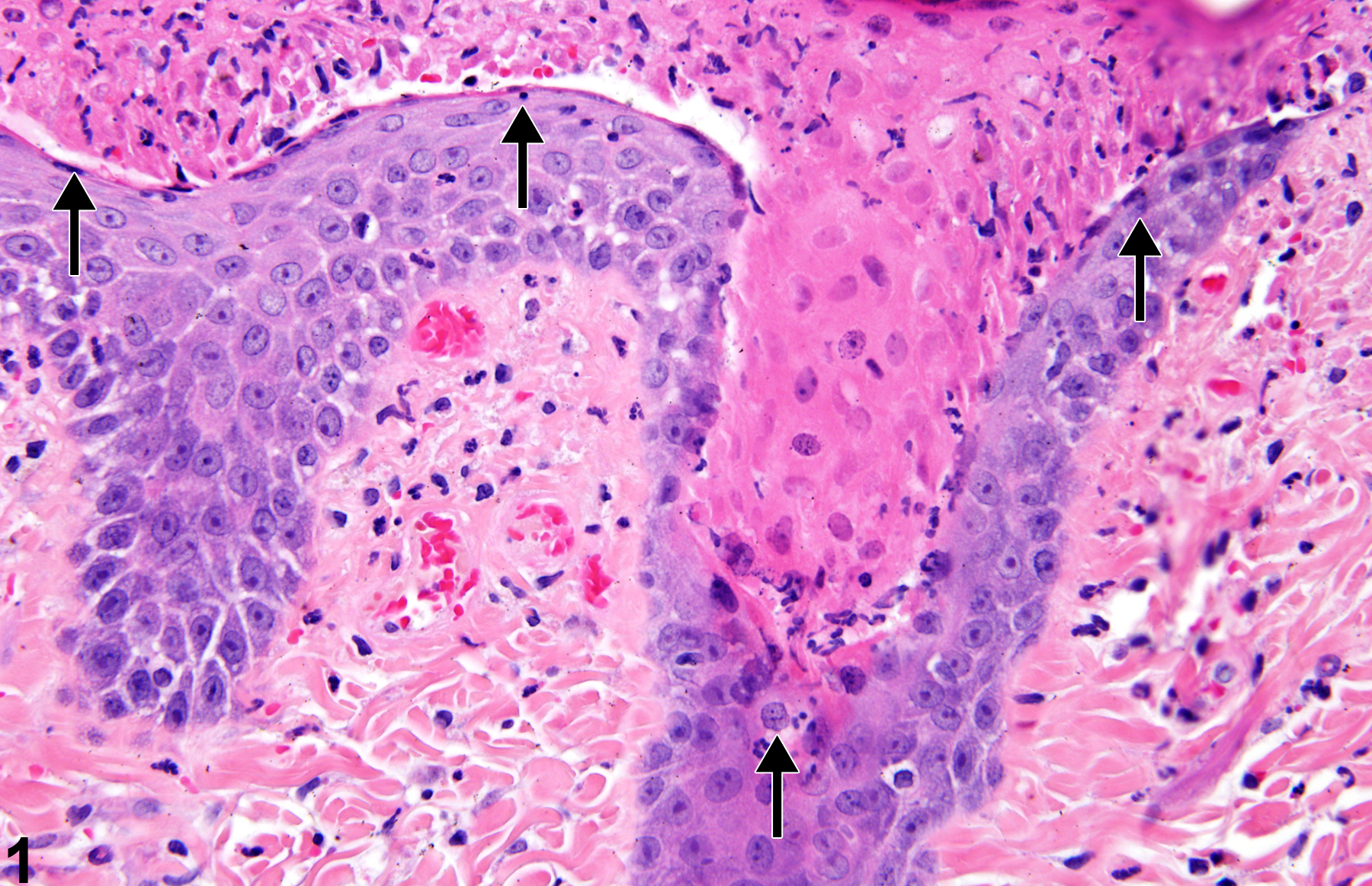

Epithelial necrosis-shrunken keratinocytes with hypereosinophilic cytoplasm and condensed nuclei (arrows) in a male F344/N rat from a 90-day study.