Reproductive System, Male

Coagulating Gland - Inflammation

Narrative

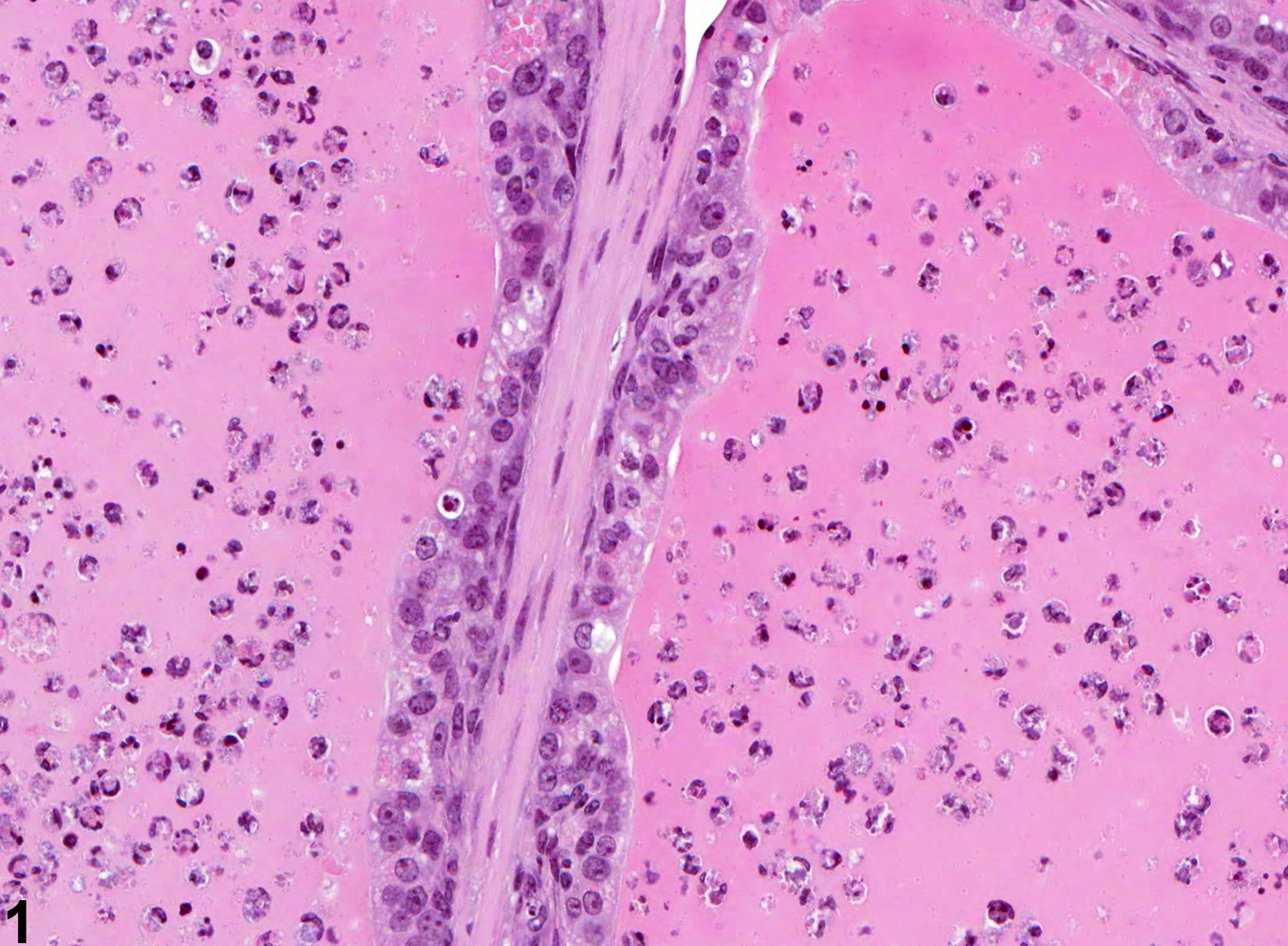

NTP studies have five standard categories of inflammation: acute, suppurative, chronic, chronic-active, and granulomatous. In acute inflammation, the predominant infiltrating cell is the neutrophil, though fewer macrophages and lymphocytes may also be present. There may also be evidence of edema or hyperemia. The neutrophil is also the predominant infiltrating cell type in suppurative inflammation, but they are aggregated, and many of them are degenerate (suppurative exudate). Cell debris from both the resident cell populations and infiltrating leukocytes, proteinaceous fluid containing fibrin, fewer macrophages, occasional lymphocytes or plasma cells, and, possibly, an infectious agent may also be present in the exudate. Grossly, these lesions would be characterized by the presence of pus. The tissue surrounding the exudate may have fibroblasts, fibrous connective tissue, and mixed inflammatory cells, depending on the chronicity of the lesion. Lymphocytes predominate in chronic inflammation. Lymphocytes also predominate in chronic-active inflammation, but there are also a significant number of neutrophils. Both lesions may contain macrophages. Granulomatous inflammation is another form of chronic inflammation, but this diagnosis requires the presence of a significant number of aggregated, large, activated macrophages, epithelioid macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells.

Arai Y, Mori T, Suzuki Y, Bern HA. 1983. Long-term effects of perinatal exposure to sex steroids and diethylstilbestrol on the reproductive system of male mammals. Int Rev Cytol 84:235-268.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6358105Boorman GA, Elwell MR, Mitsumori K. 1990. Male accessory sex glands, penis, and scrotum. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat: Reference and Atlas (Boorman GA, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, 419-428.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/9002563Bosland MC. 1992. Lesions in the male accessory glands and penis. In: Pathobiology of the Aging Rat, Vol 1 (Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Capen CC, eds). ILSI Press, Washington, DC, 443-467.

Abstract: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008994685Suwa T, Nyska A, Peckham JC, Hailey JR, Mahler JF, Haseman JK, Maronpot RR. 2001. A retrospective analysis of background lesions and tissue accountability for male accessory sex organs in Fischer-344 rats. Toxicol Pathol 29(4):467-478.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11560252Suwa T, Nyska A, Haseman JK, Mahler JF, Maronpot RR. 2002. Spontaneous lesions in control B6C3F1 mice and recommended sectioning of male accessory sex organs. Toxicol Pathol 30(2):228- 234.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11950166

Coagulating Gland - Inflammation. Acute inflammation in a male B6C3F1 mouse from a chronic study.