Musculoskeletal System

Skeletal Muscle - Inflammation

Narrative

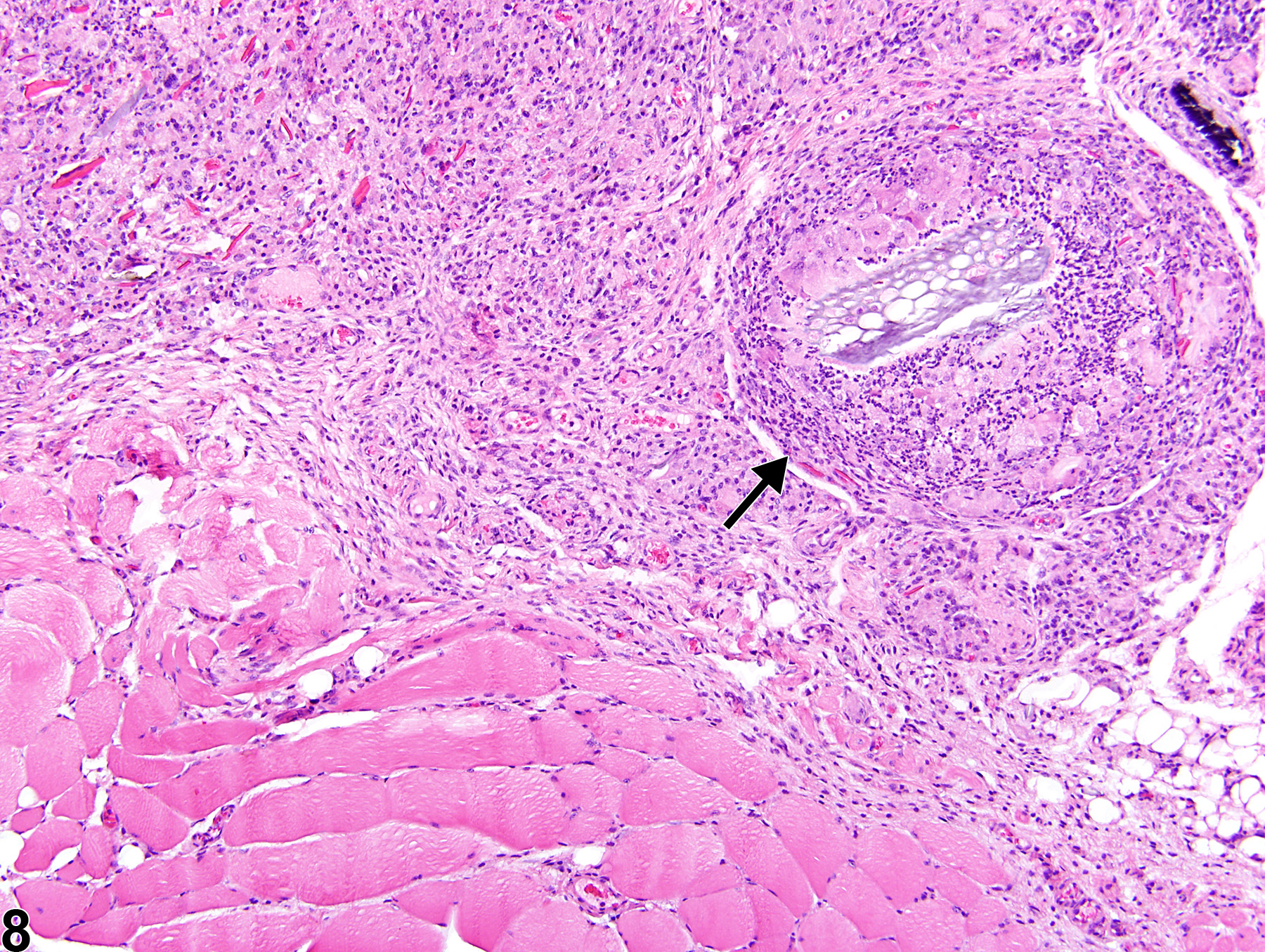

In NTP studies, there are five standard categories of inflammation: acute, suppurative, chronic, chronic-active, and granulomatous; abscesses are diagnosed as suppurative inflammation. In acute inflammation (Figure 1 and Figure 2), the predominant infiltrating cell is the neutrophil, though fewer macrophages and lymphocytes may also be present. There may also be evidence of edema or hyperemia. The neutrophil is also the predominant infiltrating cell type in suppurative inflammation (Figure 3 and Figure 4), but the neutrophils are aggregated, and many of them are degenerate (suppurative exudate). Cell debris (both from the resident cell populations and from infiltrating leukocytes); proteinaceous fluid containing fibrin, fewer macrophages, occasional lymphocytes, and/or plasma cells; and possibly an infectious agent may also be present within the exudate. Grossly, these lesions would be characterized by the presence of pus. In the tissue surrounding the exudate, there may be fibroblasts, fibrous connective tissue, and mixed inflammatory cells, depending on the chronicity of the lesion. Lymphocytes predominate in chronic inflammation. Lymphocytes also predominate in chronic-active inflammation, but a significant number of neutrophils are also present (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Both lesions may contain macrophages. Granulomatous inflammation is another form of chronic inflammation, but this diagnosis requires the presence of a significant number of aggregated, large, activated macrophages, epithelioid macrophages, or multinucleated giant cells (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Since inflammation can occur in response to, or result in, myofiber necrosis, myopathic changes in addition to edema and/or hemorrhage often occur concurrently. An inflammatory response is necessary to effectively repair damaged tissues; however, the nature, duration, and intensity of this response will crucially influence the overall outcome of repair.

Berridge BR, Van Vleet JF, Herman E. 2013. Cardiac, vascular, and skeletal muscle systems. In: Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, 3rd ed (Haschek WM, Rousseaux CG, Wallig MA, Bolon B, Ochoa R, Mahler MW, eds). Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1635-1665.

Greaves P. 2007. Musculoskeletal system. In: Histopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies, 3rd ed. Elsevier, Oxford, 160-214.

Greaves P, Seely JC. 1996. Non-proliferative lesions of soft tissues and skeletal muscle in rats, MST-1. In: Guides for Toxicologic Pathology. STP/ARP/AFIP, Washington, DC.

Greaves P, Chouinard L, Ernst H, Mecklenburg L, Pruimboom-Brees IM, Rinke M, Rittinghausen S, Thibault S, von Erichsen J, Yoshida T. 2013. Proliferative and non-proliferative lesions of the rat and mouse soft tissue, skeletal muscle, and mesothelium. J Toxicol Pathol 26(3 suppl):1S-26S.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25035576Leininger JR. 1999. Skeletal muscle. In: Pathology of the Mouse (Maronpot R, Boorman G, Gaul BW, eds). Cache River Press, St Louis, 637-643.

Mann CJ, Perdiguero E, Kharraz Y, Aguilar S, Pessina P, Serrano AL, Muñoz-Cánoves P. 2001. Aberrant repair and fibrosis development in skeletal muscle. Skelet Muscle 1:21.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21798099McDonald MM, Hamilton BF. 1990. Bones, joints, and synovia. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat: Reference and Atlas (Boorman G, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, 193-207.

Percy DH, Barthold SW. 2007. Mouse. In: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, 3rd ed. Blackwell, Ames, IA, 88-89.

Vahle JL, Leininger JR, Long PH, Hall DG, Ernst H. 2013. Bone, muscle, and tooth. In: Toxicologic Pathology: Nonclinical Safety Assessment (Sahota PS, Popp JA, Hardisty JF, Gopinath C, eds). CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 561-587.

Van Vleet JF, Valentine BA. 2007. Muscle and tendon. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 5th ed, Vol 1 (Grant MG, ed). Elsevier, Edinburgh, 185-280.

Skeletal muscle - Inflammation, Acute in a female Swiss CD-1 mouse from a chronic study. A neutrophilic infiltrate has led to necrosis and loss of muscle fibers.

All Images

Skeletal muscle - Inflammation, Granulomatous in a male Sprague Dawley rat from a subchronic study. A mixture of mononuclear cells, along with multinucleated giant cells, has replaced muscle fibers, and muscle fiber degeneration and mineralization within multinucleated giant cells (arrows) can be seen in the area of inflammation.

Skeletal muscle - Inflammation, Chronic-active in a male Tg.Ac (FVB/N) homozygous mouse from a subchronic study. A circumscribed area of granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells (arrow) and neutrophils within an extensive area of chronic-active inflammation surrounds a foreign body consistent with plant material.