Nervous System

Brain - Necrosis

Narrative

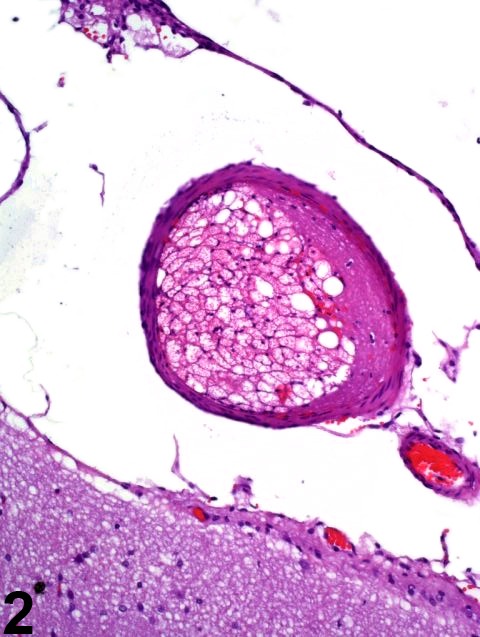

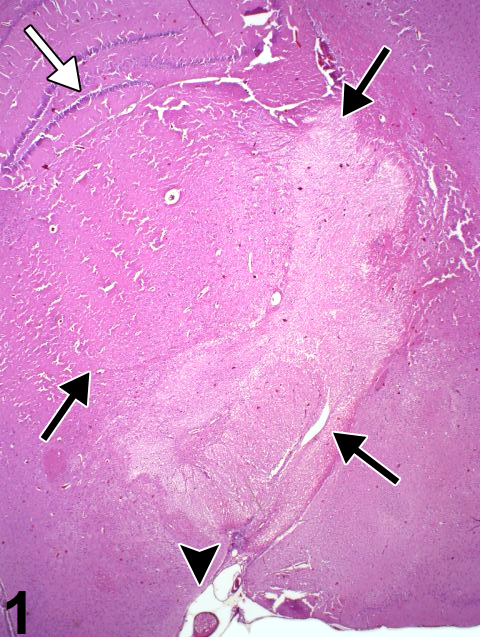

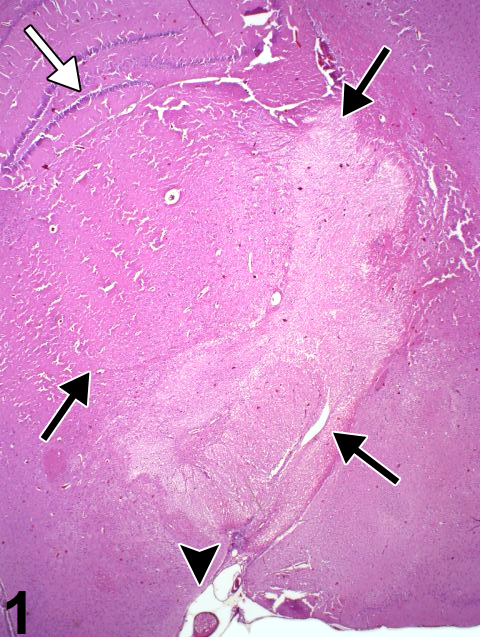

Figure 1 identifies the infarctive effects of acute vascular occlusion by an arterial embolus (arrowhead). The fibrin and fat embolus is enlarged in Figure 2. The hippocampal dentate gyrus is identified by a white arrow in Figure 1. Note the pallor signifying early necrosis of the affected region (arrows) that involves much of the thalamus, hypothalamus, cerebral peduncle, and optic tract unilaterally. In ischemic brain lesions, the typical morphologic criteria of neuronal necrosis may take more than 24 hours of survival to manifest in hematoxylin and eosin sections. At the time point shown in Figure 1, there is little, if any, evidence of inflammatory infiltrate at the margin of the lesion, indicating that the infarction is less than 24 hours old. The hippocampus is relatively spared from the ischemia. In most cases, the cause of brain infarction is incidental and/or attributable to invasive sampling techniques such as blood or marrow collection in which emboli gain access to the venous or arterial systems.

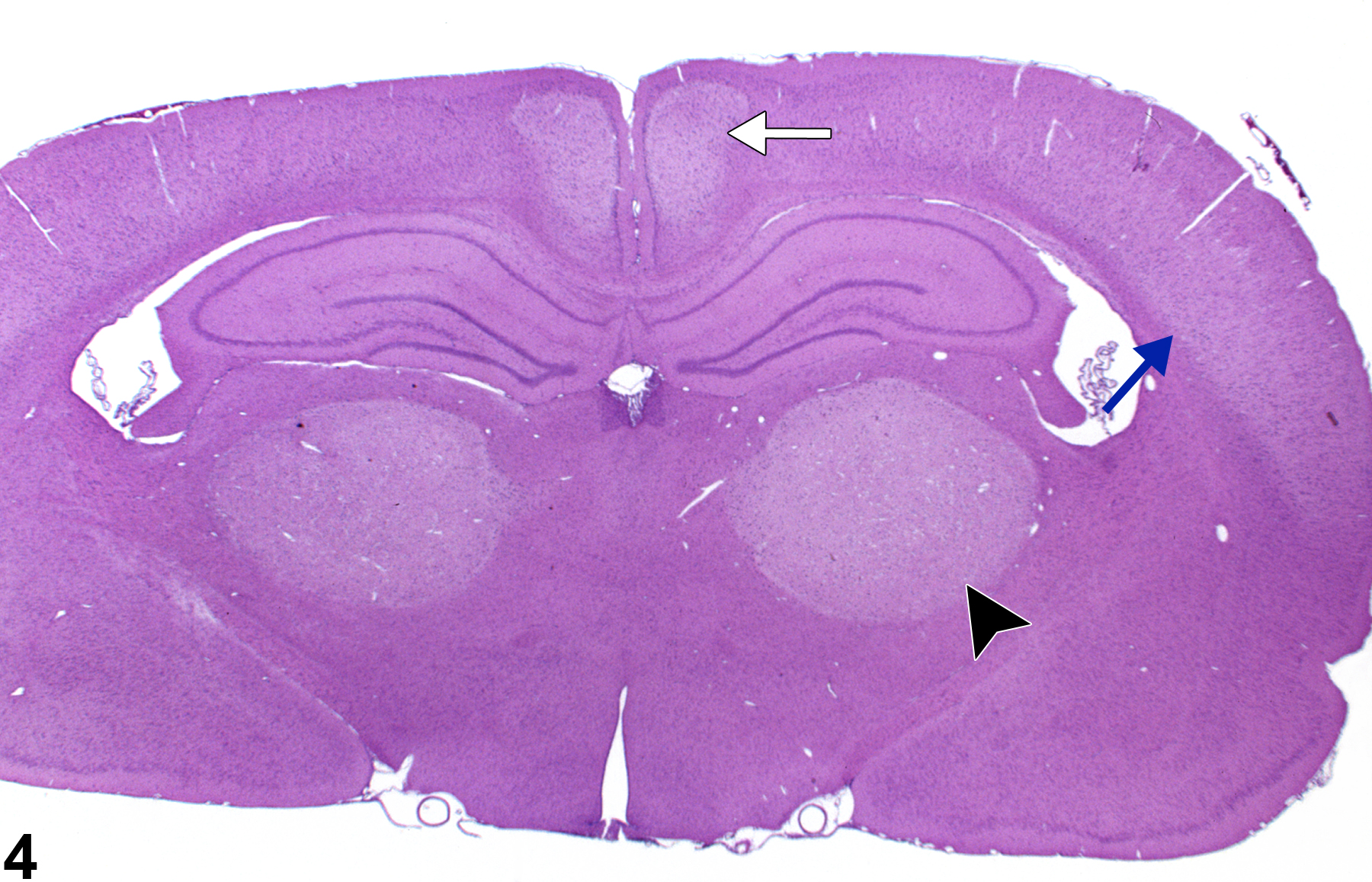

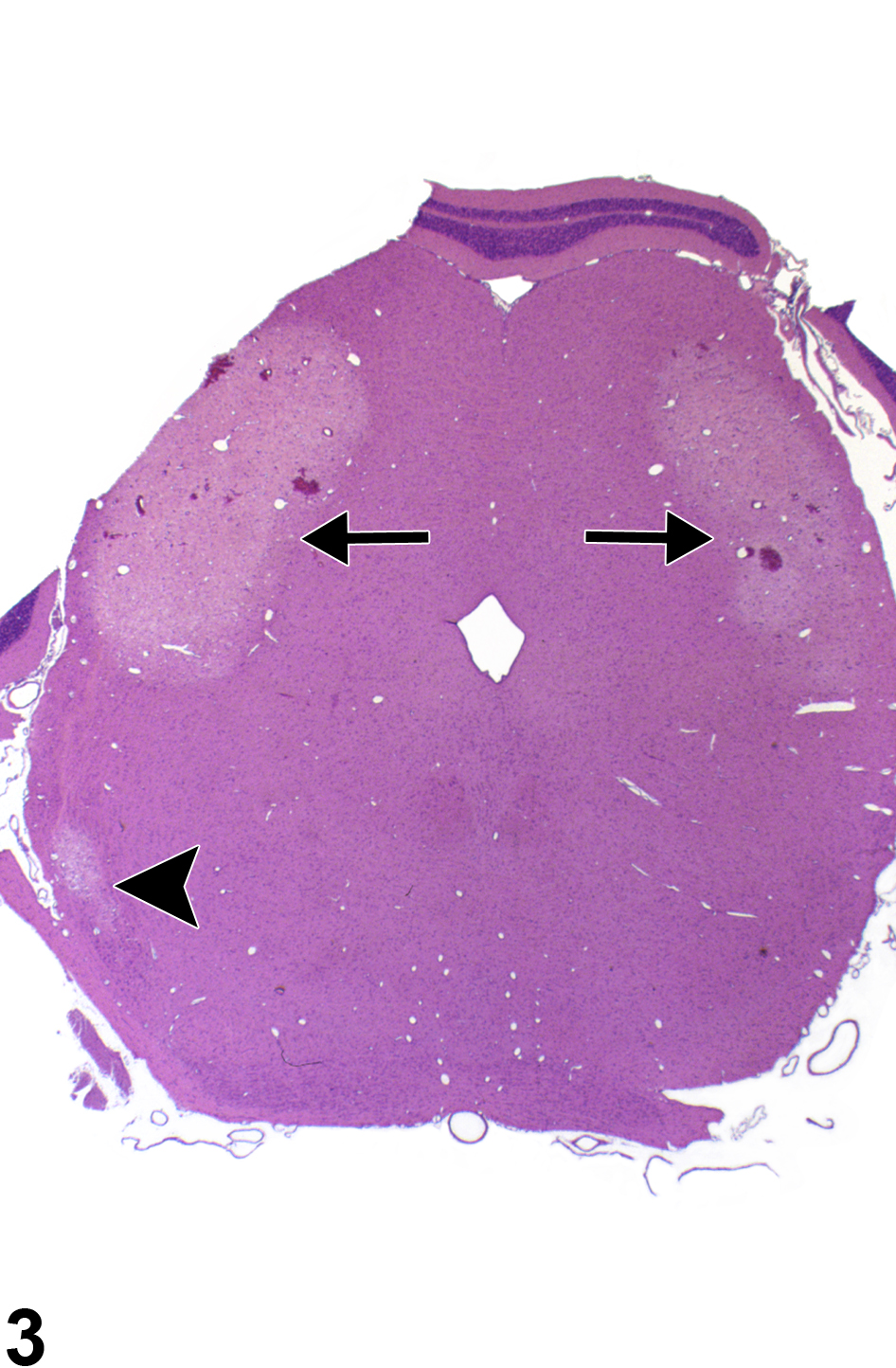

Figure 3 depicts a bilaterally symmetrical lesion of acute necrosis of the posterior colliculus. Note also the necrosis of the nucleus of the lateral lemniscus. The well-defined foci of pallor, with hemorrhage, affecting the posterior collicular nucleus bilaterally, and the nucleus of the lateral lemniscus resemble those of ischemic lesions. Like the parietal cortex, the posterior colliculus, subserving auditory reflexes, has a high metabolic rate and is particularly vulnerable to processes that interfere with neuronal energy metabolism. Similarly, Figure 4 depicts acute bilateral necrosis in the parietal cortex area 1 (blue arrow), thalamus (arrowhead), and retrosplenial cortex (white arrow). Selective vulnerability of brain regions to the effects of toxic compounds may imitate the lesions of ischemic necrosis and should be differentiated from insults of that type based on compound exposure and clinical history. Bilateral symmetry of neural lesions is generally a useful indicator of toxic, rather than ischemic, etiology.

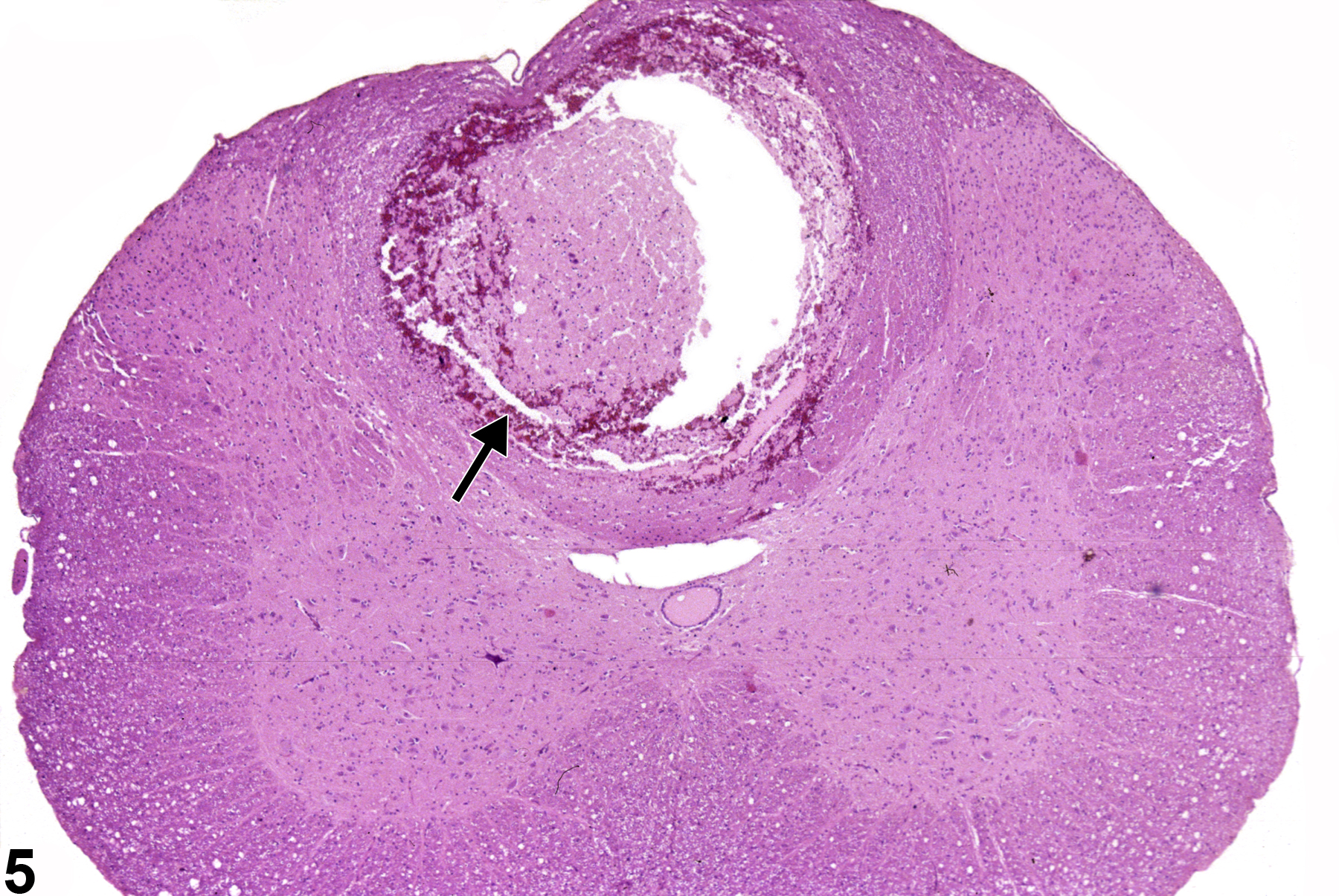

Figure 5 depicts an unusual form of total regional necrosis (arrow) of the spinal cord in the dorsal spinal funiculi. This type of spinal cord necrosis is referred to as “hematomyelia.” It is usually the result of necrosis or traumatic/neoplastic spinal compression at an adjacent site with resulting propagation of an inflammatory core of swelling, hemorrhage, and tissue disruption that progresses anteriorly and posteriorly within the spinal cord.

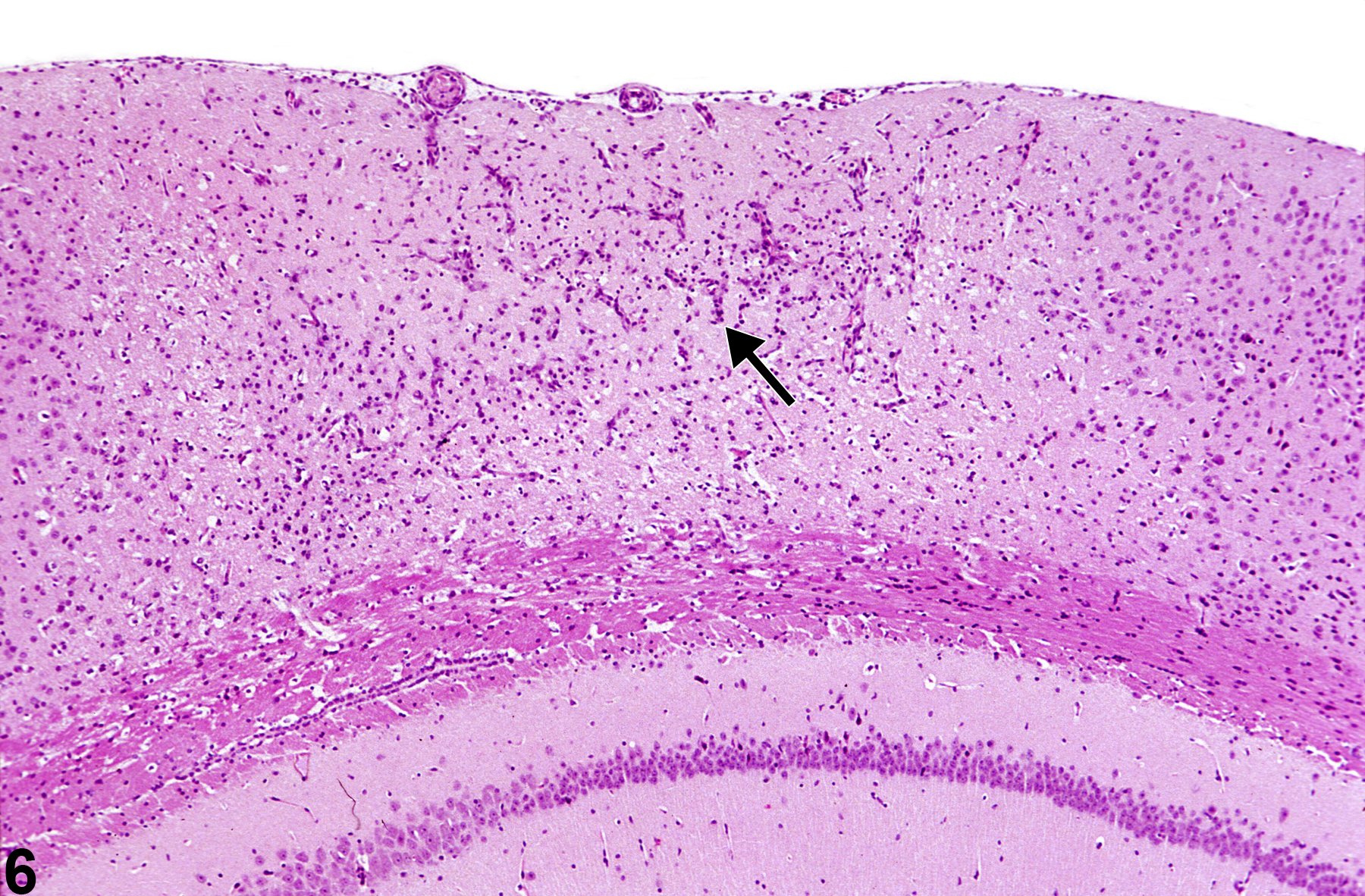

Figure 6 shows a cortical infarct with gliosis and capillary hyperplasia (arrow). The affected cortex is identified by minimal collapse of ischemic tissue, most noticeable at the meningeal extent of the lesion. Even at this low magnification, a mild degree of cortical nuclear pyknosis is apparent.

In Figure 7, a more advanced stage of cortical infarction (arrows) is shown, with gliosis and macrophage infiltration. The borders of the lesion are defined by the glial cell response, and early cavitation is proceeding throughout.

Figure 8 depicts the morphology of an infarct of known duration. At 72 hours after infarction, the capillary nuclear hypertrophy (arrow), early macrophage response, and some fragmentation of the affected tissue are evident.

Depicted in Figure 9 is a later stage of cortical infarction where there is loss of tissue and collapse of the cortical structure, creating a depression at the meningeal surface. This subpial atrophy of the cortex is also accompanied by residual macrophages in the leptomeningeal spaces and cavitated areas (arrows). While astrocytic hypertrophy is not apparent in this hematoxylin and eosin section, a glial fibrillary acidic protein stain would demonstrate a significant response coinciding with the duration of the insult.

Figure 10 depicts the cellular responses in cortical infarction of known 72 hour duration (PB Little, personal observation). Note the hypertrophic and hyperplastic state of the capillary endothelium and the prominent macrophage presence (arrows). These macrophages have differentiated from resident microglial cells or blood-borne monocytic cells and are in the process of phagocytosis of brain lipid in the affected ischemic region. They are referred to as lipid phagocytes or, more commonly, as “gitter cells.” They can be further identified by their autofluorescence at 365 nm wavelength and by their positive staining with periodic acid Schiff or various lipid stains such as Sudan III or oil red O.

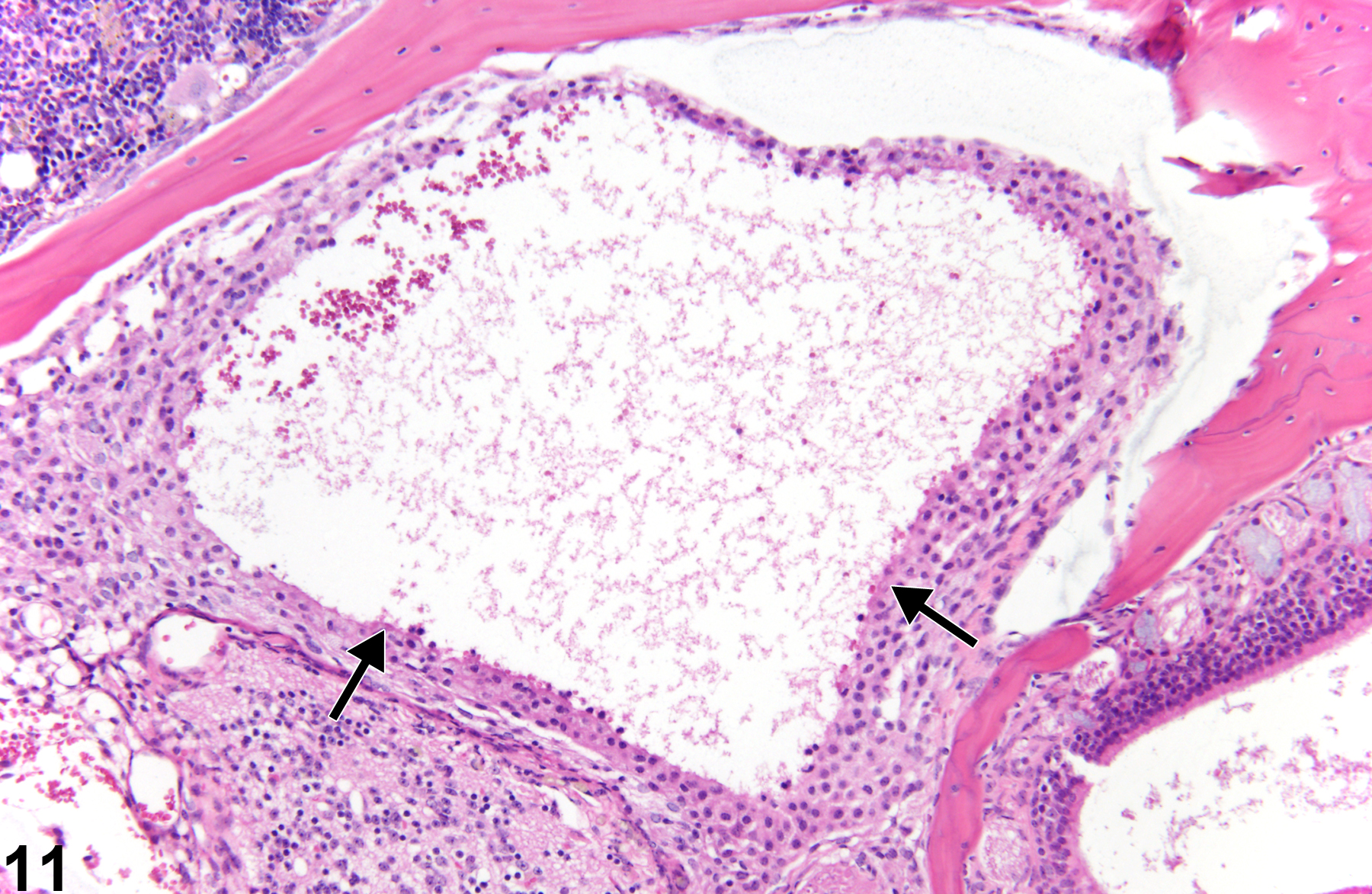

Figure 11 is an example of severe olfactory bulb necrosis that has often been referred to as malacia. There is loss of much of the substance of the organ accompanied by central hemorrhage and necrotic debris (arrows). Malacia is a process of total necrosis of a region of brain and describes the gross palpable texture of the large affected necrotic region of brain. Histologically, in NTP studies, malacia is histologically diagnosed as necrosis. Microscopically, all elements of the neural tissue in a lesion are necrotic. Here, the process has advanced to liquefaction of necrotic elements, leaving little but amorphous debris and some hemorrhage. Ultimately, such an area is destined to become a cyst filled with cerebrospinal fluid. In regions of advanced neural necrosis, much of the recognizable tissue is lost. It is important to ascribe the process to necrosis rather than autolysis, which the lack of viable neural tissue may suggest. The presence of normal morphology of adjacent tissue as shown in Figure 11 is helpful in forming a diagnosis of necrosis.

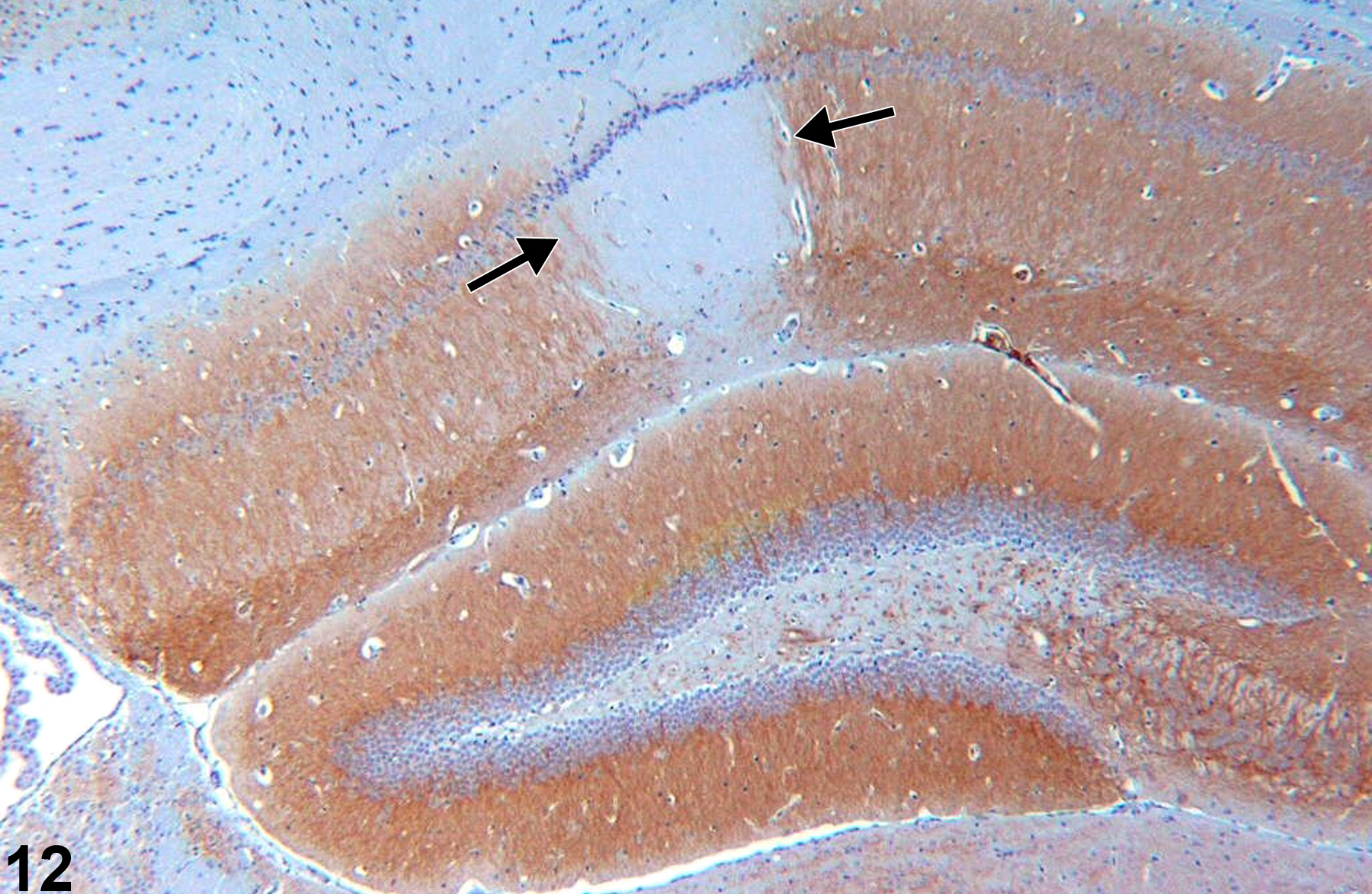

Figure 12 outlines the CA1 region in the hippocampus in which there is ischemic necrosis. Microtubule-associated protein immunohistochemical technique negatively outlines the necrotic zone (arrows). Similarly, if cerebral infarction is anticipated in a study, the use of triphenyltetrazolium is valuable to grossly define the region of involvement. Such special stains are not used in routine first-tier evaluation, but it is useful to be aware of them for special circumstances.

Calloni RL, Winkler BC, Ricci G, Poletto MG, Homero WM, Serafini EP, Corleta OC. 2010. Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats as an experimental model of brain ischemia. Acta Cir Bras 25:428-433.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20877953Sicard KM, Henninger V, Fisher V, Duong V, Ferris CF. 2006. Long-term changes of functional MRI-based brain function, behavioral status, and histopathology after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke 37:2593-2600.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16946164

Appearance of a thalamic infarct at low magnification, identified by pallor within the zone of the black arrows, in an F344/N rat. The dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is identified by a white arrow. This infarct was the result of an arterial embolus (arrowhead), shown at higher magnification in Figure 2.

All Images

Appearance of a thalamic infarct at low magnification, identified by pallor within the zone of the black arrows, in an F344/N rat. The dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is identified by a white arrow. This infarct was the result of an arterial embolus (arrowhead), shown at higher magnification in Figure 2.

Acute necrosis of the posterior colliculus, a bilaterally symmetrical lesion (arrows), in the whole mount of a section in a male F344/N rat from a 4-day study. This resulted from the selective vulnerability of this brain region to toxin-induced impaired energy metabolism. The arrowhead identifies necrosis of the nucleus of the lateral lemniscus.