Respiratory System

Lung - Emphysema

Narrative

Emphysema can result from a number of causes. Various proteases (e.g., porcine pancreatic elastase, papain, and human neutrophils elastase), endotoxin, cigarette smoke, and other agents have been used in rodents to model emphysema in humans. Inflammatory lesions may produce overinflation of the lungs by obstructing airways and allowing inhalation but hindering exhalation (the "ball and valve effect"); this must be differentiated from true emphysema. Sendai virus has been reported to cause emphysema in neonatal rats, presumably as a result of epithelial necrosis and inflammation, though infection by this agent is now rare due to modern animal husbandry practices.

Braber S, Koelink PJ, Henricks PA, Jackson PL, Nijkamp FP, Garssen J, Kraneveld AD, Blalock JE, Folkerts G. 2011. Cigarette smoke-induced lung emphysema in mice is associated with prolyl endopeptidase, an enzyme involved in collagen breakdown. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300:L255-L265.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21112944Castleman WL. 1992. Effects of infectious agents and other factors on the lungs. In: Pathobiology of the Aging Rat, Vol 1 (Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Capen CC, eds). ILSI Press, Washington, DC, 181-191.

Clauss M, Voswinckel R, Rajashekhar G, Sigua NL, Fehrenbach H, Rush NI, Schweitzer KS, Yildirim AÖ, Kamocki K, Fisher AJ, Gu Y, Safadi B, Nikam S, Hubbard WC, Tuder RM, Twigg HL, Presson RG, Sethi S, Petrache I. 2011. Lung endothelial monocyte-activating protein 2 is a mediator of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest 121:2470-2479.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21576822Lanzetti M, Lopes AA, Ferreira TS, de Moura RS, Resende AC, Porto LC, Valenca SS. 2011. Mate tea ameliorates emphysema in cigarette smoke-exposed mice. Exp Lung Res 37:246-257.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21210748Mahadeva R, Shapiro SD. 2002. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 3: Experimental animal models of pulmonary emphysema. Thorax 57:908-914.

Full Text: http://thorax.bmj.com/content/57/10/908.fullPires KM, Bezerra FS, Machado MN, Zin WA, Porto LC, Valença SS. 2011. N-(2-mercaptopropionyl)-glycine but not allopurinol prevented cigarette smoke-induced alveolar enlargement in mouse. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 175:322-330.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21187166Renne, R, Brix A, Harkema J, Herbert R, Kittle B, Lewis D, March T, Nagano K, Pino M, Rittinghausen S, Rosenbruch M, Tellier P, Wohrmann T. 2009. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse respiratory tract. Toxicol Pathol 37(suppl):5S-73S.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20032296Stemmer KL, Bingham E, Barkley W. 1975. Pulmonary response to polyurethane dust. Environ Health Perspect 11:109-113.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1175548Tátrai E, Brózik M, Náray M, Adamis Z, Ungváry G. 2001. Combined pulmonary toxicity of cadmium chloride and sodium diethyldithiocarbamate. J Appl Toxicol 21:101-105.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11288132Triantaphyllopoulos K, Hussain F, Pinart M, Zhang M, Li F, Adcock I, Kirkham P, Zhu J, Chung KF. 2011. A model of chronic inflammation and pulmonary emphysema after multiple ozone exposures in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300:L691-L700.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21355040Volonte D, Galbiati F. 2009. Caveolin-1, cellular senescence and pulmonary emphysema. Aging (Albany NY) 1:831-835.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20157570

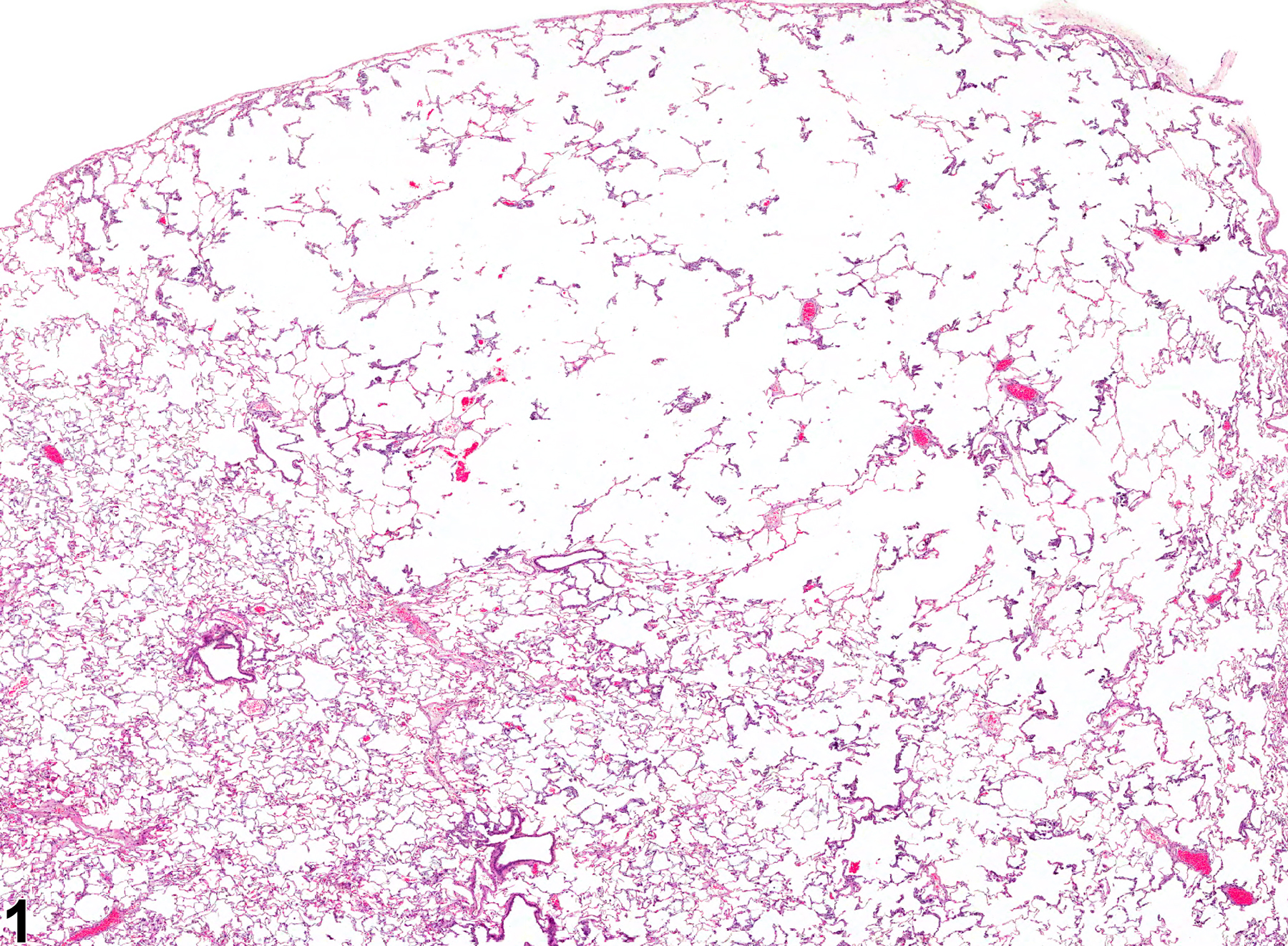

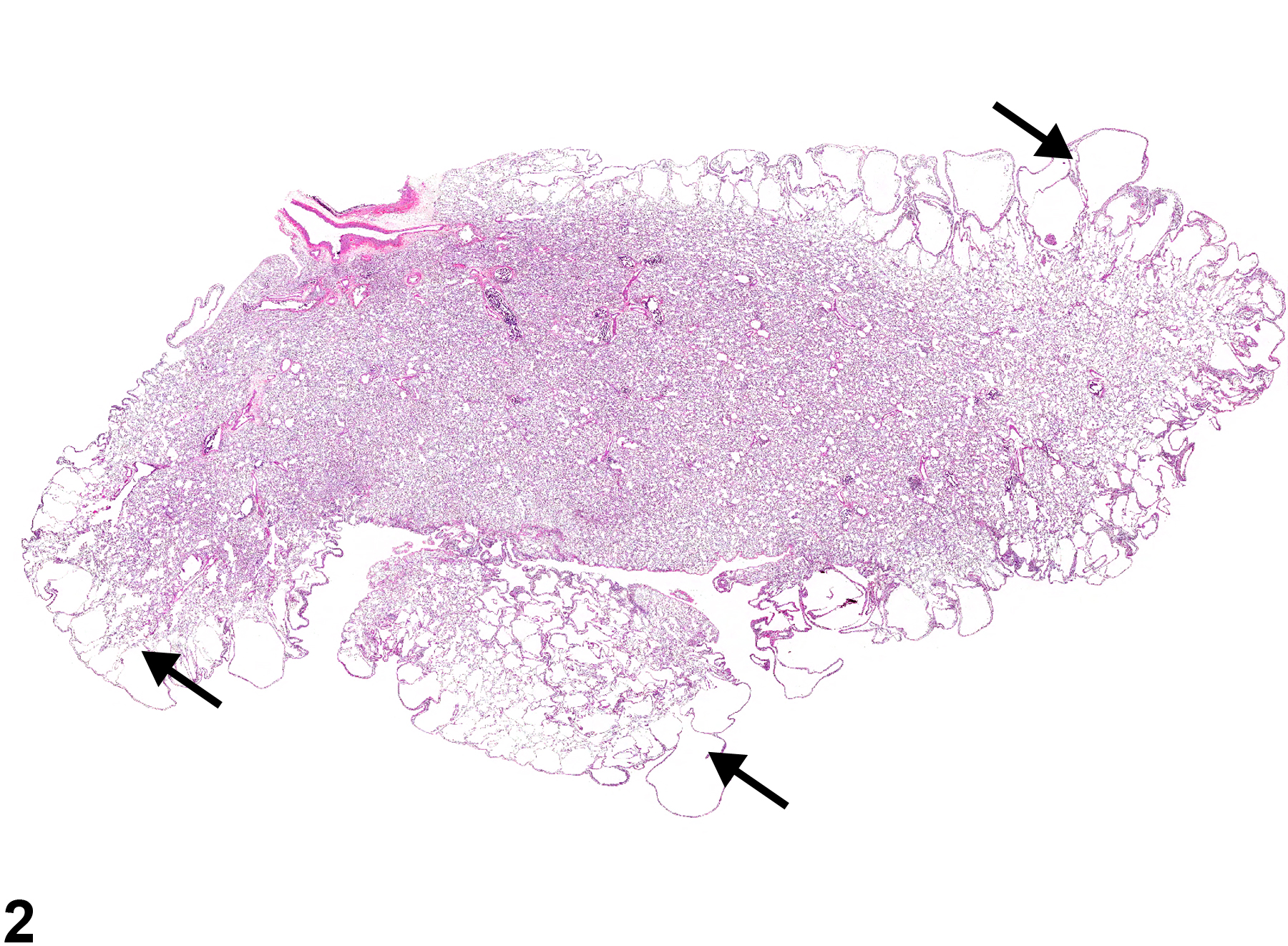

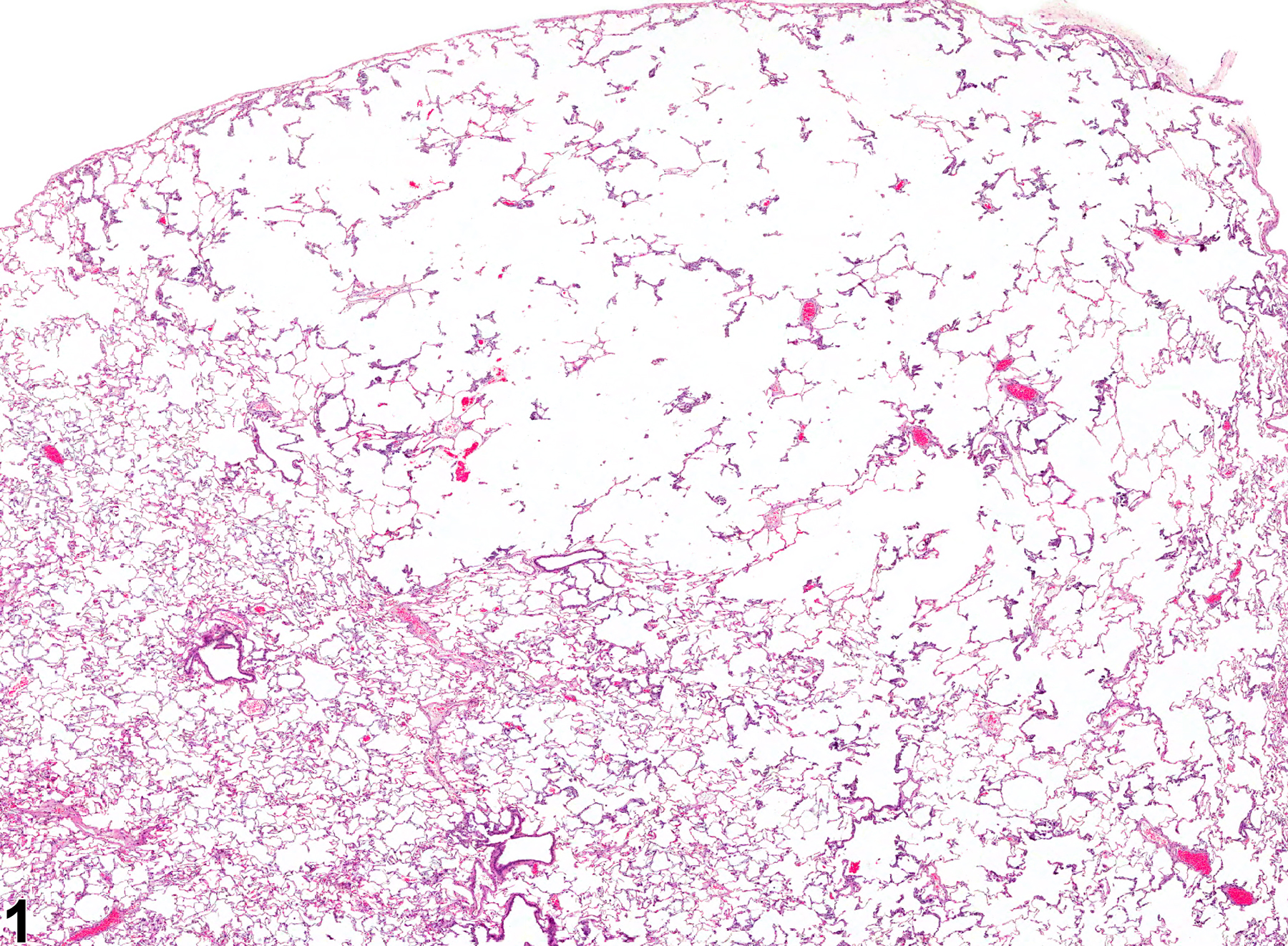

Lung - Emphysema in a male F344/N rat from a chronic study. The alveolar septa are absent in a region of the lung, creating one large airspace.