Urinary System

Urinary Bladder - Calculus/Crystal

Narrative

Arnold LL, Cano M, St John MK, Healy CE, Cohen SM. 2001. Effect of sulfosulfuron on the urine and urothelium of male rats. Toxicol Pathol 29:344-352.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11444256Clayson DB, Fishbein L, Cohen SM. 1995. Effects of stones and other physical factors on the induction of rodent bladder cancer. Food Chem Toxicol 33:771-784.

Abstract: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0278691595000443Cohen SM. 1999. Calcium phosphate-containing urinary precipitate in rat urinary bladder carcinogenesis. In: Species Differences in Thyroid, Kidney and Urinary Bladder Carcinogenesis (Capen CC, Dybing E, Rice JM, Wilbourn JD, eds). IARC Scientific Publication No. 147. International Agency for Scientific Cancer, Lyon, France, 175-189.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10627184Cohen SM, Arnold LL, Cano M, Ito N, Garland EM, Shaw RA. 2000. Calcium phosphate-containing precipitate and the carcinogenicity of sodium salts in rats. Carcinogenesis 21:783-792.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10753216Cohen SM, Ohnishi T, Clark NM, He J, Arnold LL. 2007. Investigations of rodent urinary bladder carcinogens: Collection, processing, and evaluation of urine and bladders. Toxicol Pathol 35: 337-347.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17455081Fukushima S, Murai T. 1999. Calculi, precipitates and microcrystalluria associated with irritation and cell proliferation as a mechanism of urinary bladder carcinogenesis in rats and mice. In: Species Differences in Thyroid, Kidney and Urinary Bladder Carcinogenesis (Capen CC, Dybing E, Rice JM, Wilbourn JD, eds). IARC Scientific Publication No. 147. International Agency for Scientific Cancer, Lyon, France, 159-174.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10627184Kahn SR. 1998. Calcium oxalate urolithiasis, rat. In: Monographs on Pathology of Laboratory Animals: Urinary System, 2nd ed (Jones TC, Hard GC, Mohr U, eds). Springer, Berlin, 431-438.

Abstract: http://www.ilsi.org/publications/urinarysystem.pdfTannehill-Gregg SH, Dominick MA, Reisinger AJ, Moehlenkamp JD, Waites CR, Stock DA, Sanderson TP, Cohen SM, Arnold LL, Schilling BE. 2009. Strain-related differences in urine composition of male rats of potential relevance to urolithiasis. Toxicol Pathol 37:293-305.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19380840Wojcinski ZW, Renlund RC, Barsoum NJ, Smith GS. 1992. Struvite urolithiasis in a B6C3F1 mouse. Lab Anim 26: 81-287.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1447906Yarlagadda SG, Perazella MA. 2008. Drug-induced crystal nephropathy: An update. Expert Opin Drug Safety 7:147-158.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18324877

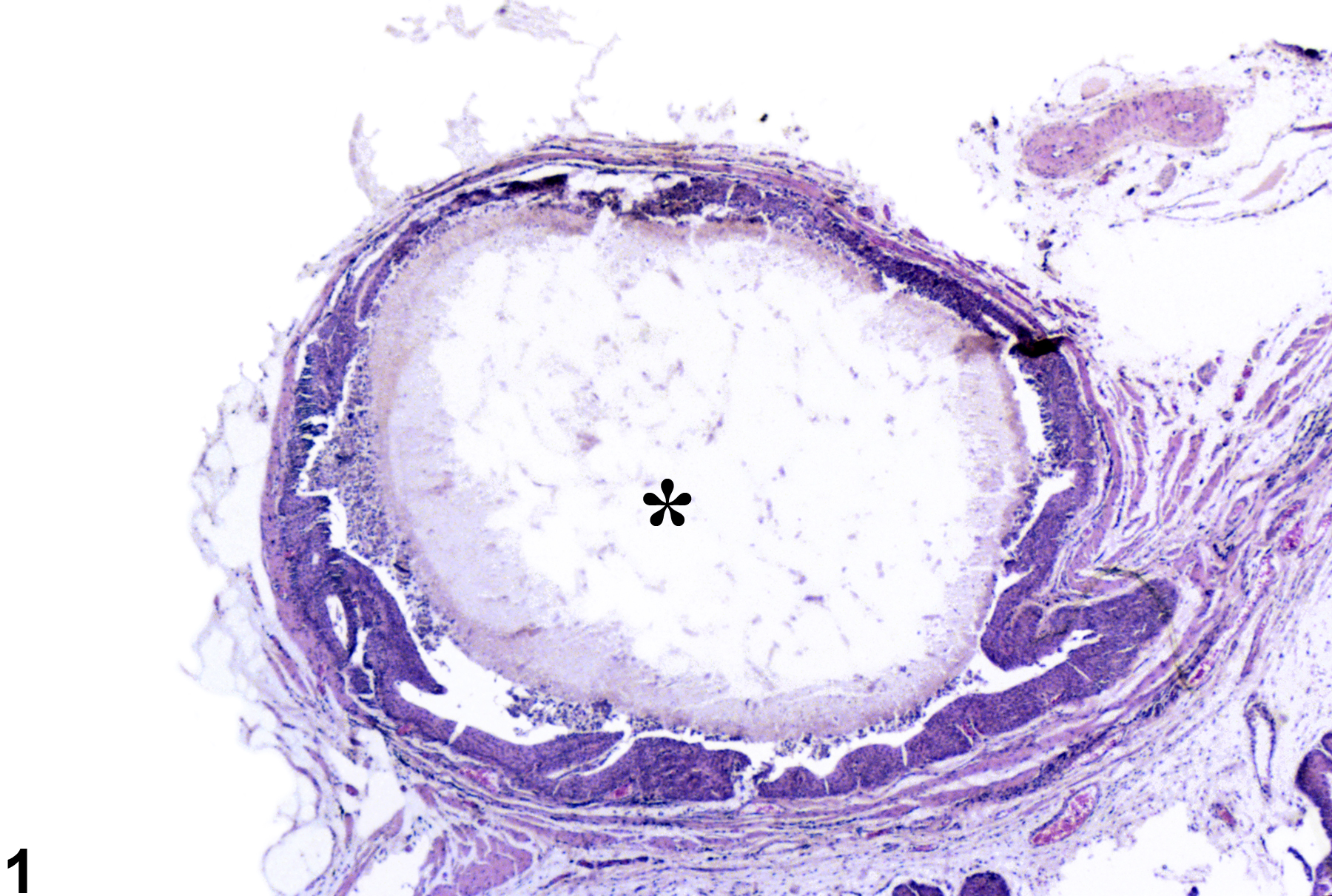

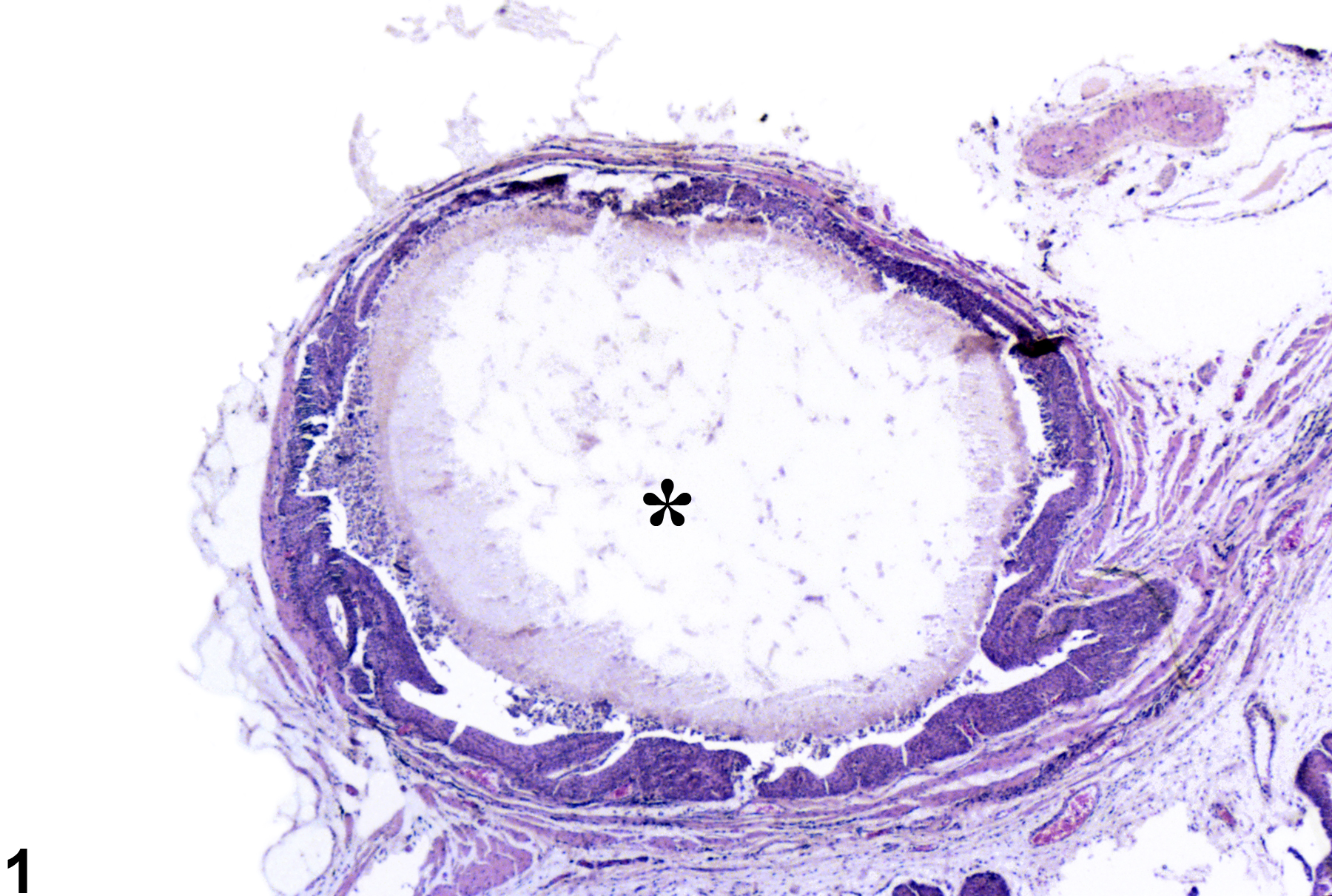

A calculus (asterisk) fills the entire bladder lumen from a male F344/N rat in a chronic study.