Urinary System

Urinary Bladder - Inflammation

Narrative

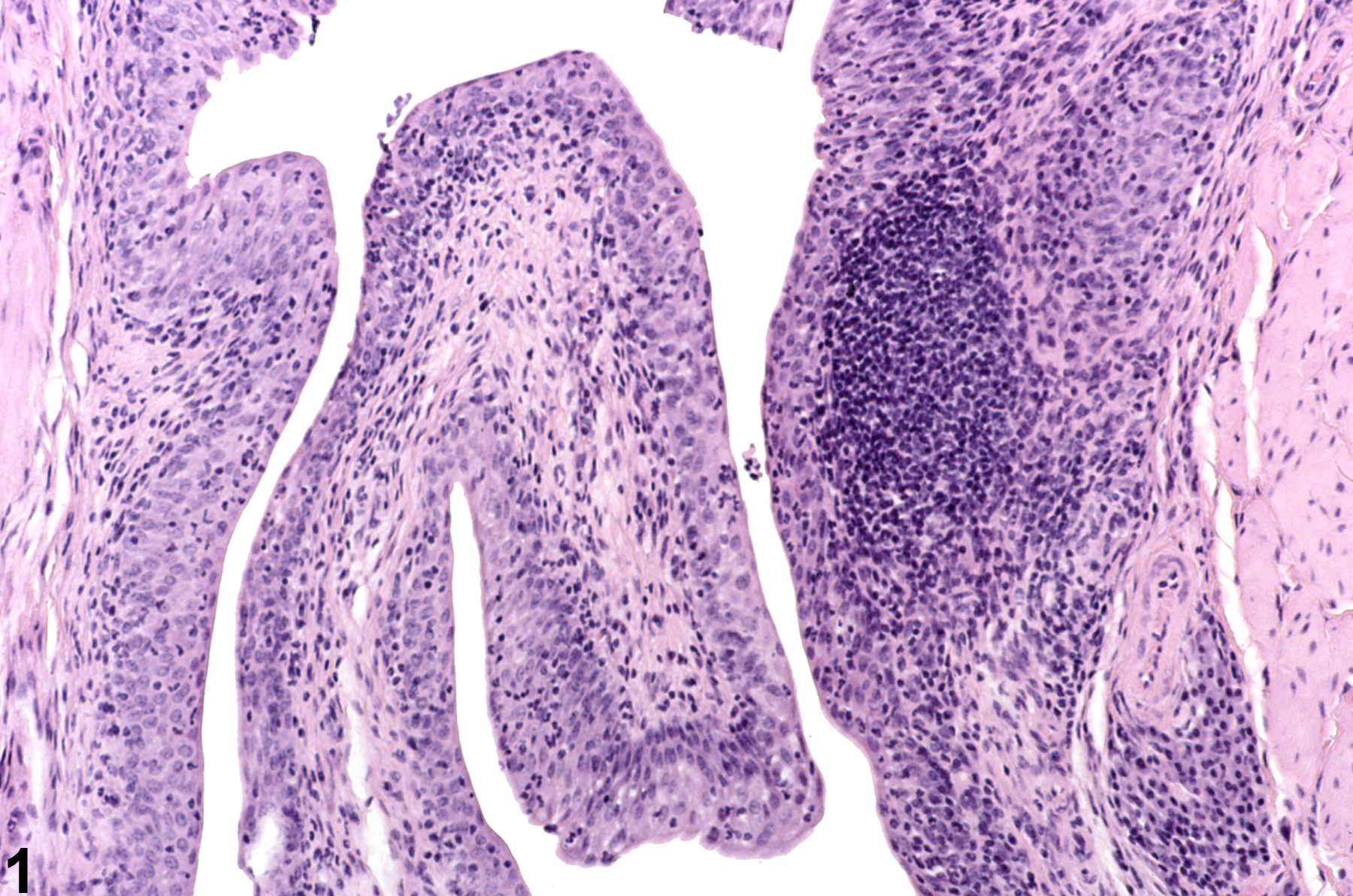

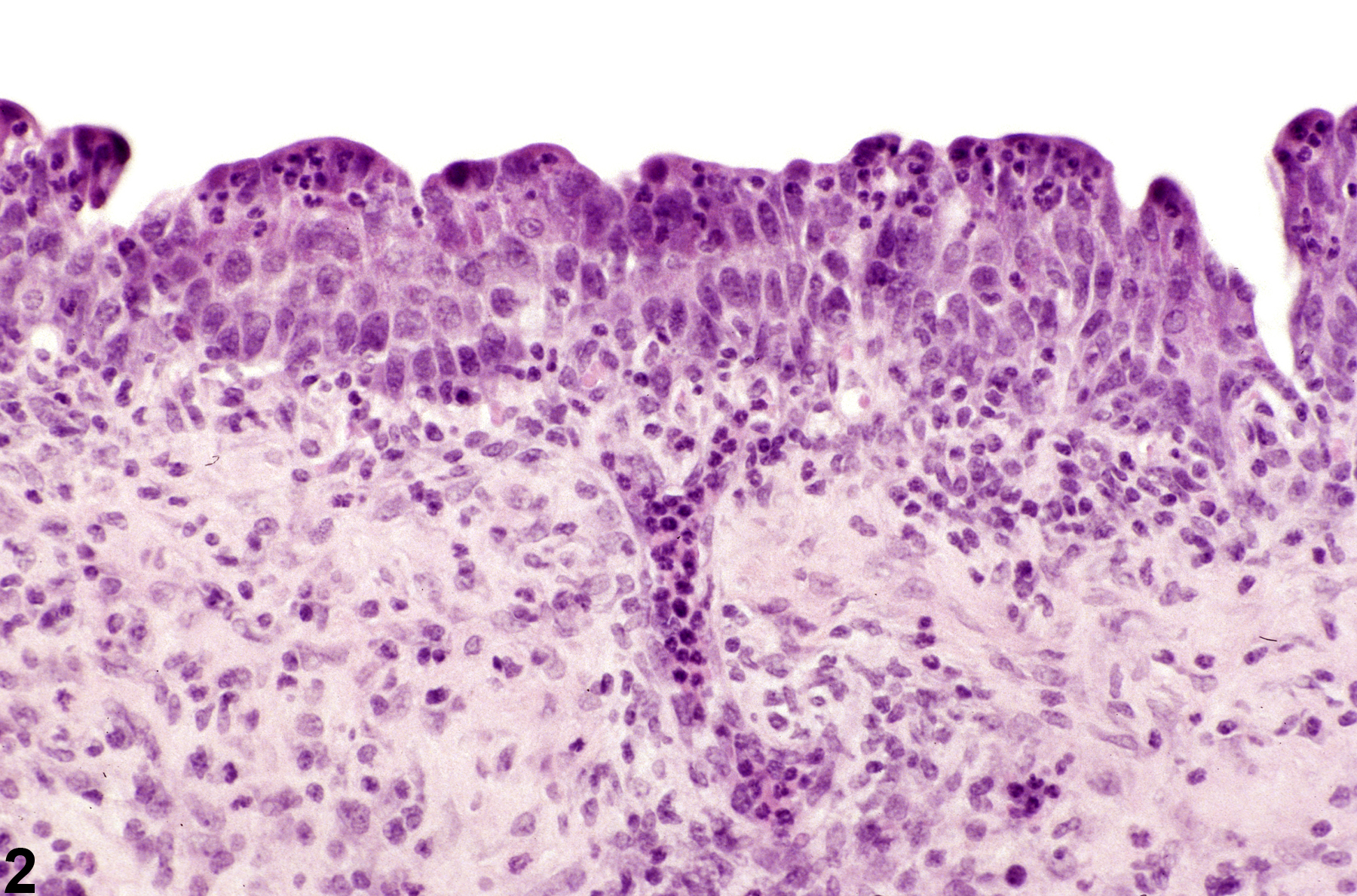

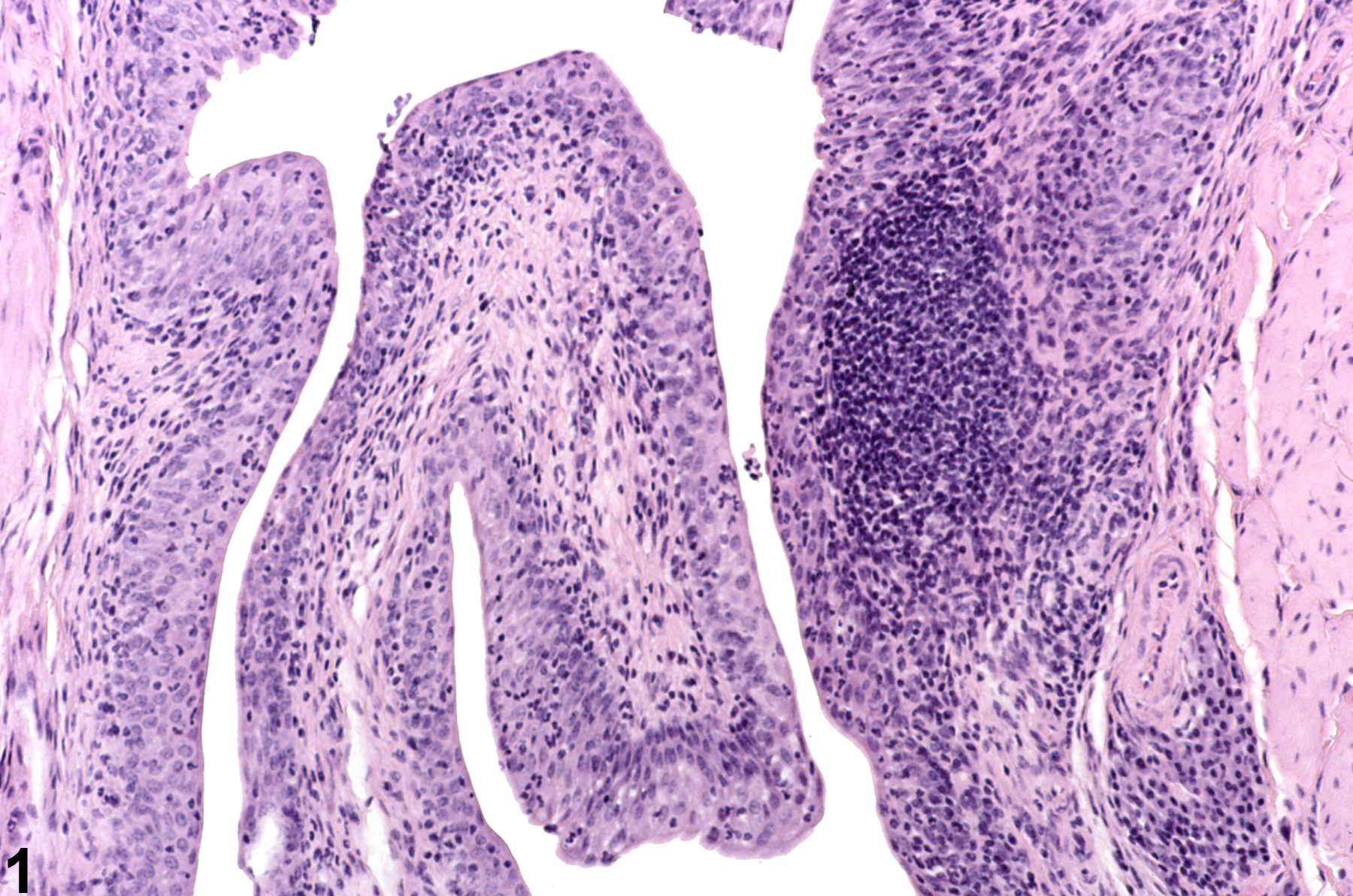

Inflammatory cells can be seen anywhere in the bladder, including the lumen, mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis (Figure 1). Hemorrhage, necrosis, urothelial hyperplasia, and fibrosis may be evident, depending on the lesion (Figure 2). In most instances, inflammation arises from bacterial infections or the presence of calculi. Inflammation may also be a direct consequence of chemical administration.

Frith CH. 1979. Morphologic classification of inflammatory, nonspecific, and proliferative lesions of the urinary bladder of mice. Invest Urol 16:435-444.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/571862Gaillard ET. 1999. Ureter, urinary bladder and urethra. In: Pathology of the Mouse: Reference and Atlas (Maronpot RR, Boorman GA Gaul BW, eds). Cache River Press, Vienna, IL, 235-258.

Jokinen MP. 1990. Urinary bladder, ureter, and urethra. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat: Reference and Atlas (Boorman GA, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, 109-126.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/9002563

Chronic-active inflammation involving the urothelium and subepithelial layers from a male F344/N rat in a chronic study.