Integumentary System

Mammary Gland

Narrative

The mammary gland in rodents undergoes complex developmental and age-related changes. Therefore, access to information about hormonal status, diet, age, and pregnancy status can aid in the appropriate microscopic evaluation of mammary gland tissue. Additionally, specific tissues that should be evaluated microscopically alongside the mammary gland include tissues of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis, the adrenal gland, and accessory sex glands (e.g., prostate, preputial, and clitoral glands). In mice, it is also important to know the mouse mammary tumor virus status, as positive status influences the incidence of hyperplasia and neoplasia. In this section, “rodent” will be used when information refers to rats and mice; when species are different, each species will be discussed separately.

Anatomy and sectioning

Female mice have five pairs of mammary glands, including three in the cervicothoracic region and two in the inguinoabdominal region. Male mice usually have four pairs of glands and lack both nipples and collecting ducts. Rats of both sexes have six pairs of mammary glands, including three pairs in the cervicothoracic region and three pairs in the inguinoabdominal region. Similar to male mice, male rats also lack nipples. The pectoralis muscle runs within the cervicothoracic glands.

In female rodents, each individual gland contains a single lobe and a single lactiferous duct. The basic milk producing unit is called the terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU), which develops in female rats upon sexual maturity and during pregnancy in mice. A single gland can have marked microscopic variability in TDLU morphology. Milk drains from TDLUs into the extralobular terminal ducts (also called interlobular ducts), and then the collecting ducts. Five to 10 secondary collecting ducts drain into a single lactiferous duct/sinus before finally reaching the ostia of the nipples (except in male mice, where collecting ducts and external nipples are absent).

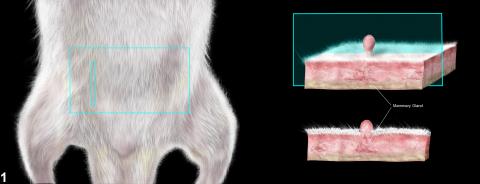

For studies conducted by the Division of Translational Toxicology (DTT) at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (Figure 1), mammary gland with adjacent skin (unless requesting mammary gland whole mount) should be collected for general toxicity studies during necropsy, and complete histopathological evaluation of mammary gland and adjacent skin should be done separately. It is recommended that a section of skin, approximately 2.5 cm wide x 3.5 cm long, with subcutaneous tissue and mammary gland attached, shall be collected from the inguinal region with the longest portion oriented along the longitudinal axis of the body. For the selected studies, as directed by protocol, the skin and mammary gland should be collected separately. The entire fourth and fifth mammary glands shall be collected and laid flat on an index card prior to immersion in 10% NBF. For these studies, skin should be collected without the mammary gland attached.

The section of control skin with the mammary gland attached (taken from the inguinal region) shall be kept in a separate labeled cassette to avoid confusion with the skin sampled at the site of application. The section (strip) to be embedded shall be approximately 0.3-0.4 cm x 1.5 cm and shall be embedded cut surface down (on end) in the cassette. For dermal studies, the strip of control skin is taken in the inguinal area to include the mammary gland. The section of skin taken from the site of application shall be trimmed so that the orientation of the examined section is parallel to the longitudinal axis of the body and embedded cut surface down (Figure 1). For mammary glands collected for histopathological examination (right fourth and fifth glands prior to postnatal day 90, fourth only in postnatal day 90 rats), the trimmed sections shall include the region deep to the fourth nipple and the lymph node. These glands shall be sectioned in the dorsoventral plane (i.e., parallel to the animal’s body). For detailed instructions, please follow the anatomic pathology chapter of the DTT specifications.

Figure 1. The section of skin taken from the site of application shall be trimmed so that the orientation of the examined section is parallel to the longitudinal axis of the body and embedded cut surface down.

Development

Fetal

Mammary tissue is of ectodermal origin and develops along the mammary line/ridge that overlies specialized mesoderm. Initial epithelial development takes place as an epithelial bud. The epithelium in between the buds atrophies to form the individual glands, with each gland centered on a primitive nipple. During the fetal stage, the buds do not develop into distinct lobules/alveoli in either sex rodents.

Hormones are a key driver of mammary gland formation during neonatal development. Androgens initiate differentiation of the male phenotype by promoting atrophy of the rudimentary buds. Specifically, testosterone from the fetal testis triggers condensation of the stroma, leading to epithelial bud atrophy. This atrophy renders male mice resistant to mammary changes caused by altered hormone status later in life (e.g., castration). Male rodent nipples regress during embryonic development. In contrast, androgen levels can alter mammary gland morphology in both sexes in rats. Androgen depletion in the male rat fetus can alter the normal lobuloalveolar morphology to the tubuloalveolar morphology typical of female rats (historically referred as “feminization”).

Androgen administration in female rats can trigger a change from the normal tubuloalveolar to the typical male-like lobuloalveolar morphology (historically referred “masculinization”). The use of syndromic terms feminization and masculinization is not recommended and may be misleading because of their implications in humans. In contrast, fetal exposure, or depletion of androgens in male and female mice does not cause this change because of lack of androgen responsiveness.

Nipple retention (NR) is another morphometric biomarker of fetal androgen action. As previously noted, male rodents lack nipples. Instead, male rat pups have pigmented patches (areolas) along the milk lines corresponding to where females have nipples, which can be observed around post-natal days 12/13. Androgen from fetal testes instigates the atrophy of rudimentary buds in the male rat. Therefore, androgen depletion or a low level of androgen signaling during this developmental frame will allow nipple formation in male rats, leading to nipple retention (NR). Hence, it is often used as a retrospective biomarker of fetal androgen action in rats.

The role of female hormones in the development of mammary glands of rodents is less clear. However, in vitro studies indicate that estrogens promote mouse mammary gland development but inhibit development in rats. It appears that progesterone is not critical for mouse mammary gland development (in utero deficiencies do not preclude adult maturation of the gland). The role of progesterone in rats has not been fully elucidated.

Neonatal through puberty development

Neonatal rodents of both sexes have a single, central lactiferous duct, several branching secondary ducts, and numerous tertiary ducts. Mammary development involves the extension of epithelial cells into the fat pad. The fat pads contain adipocytes, preadipocytes, fibroblasts, and a thin stromal cell layer that surrounds the epithelial buds.

Females

In female rodents, differentiation of the primitive milk bud progresses during puberty into terminal end bud units (TEBs), which consists of epithelial, myoepithelial cells, and cap cells (which include stem cells). This differentiation is characterized by rapid elongation and branching of the ducts with concurrent hypertrophy of the fat pad. Lateral branches of mature ducts produce new end buds, which may eventually form lobules. TEBs are also the main hormone-responsive portion of the mammary gland in sexually mature rodents, and respond primarily to prolactin, estrogen, and progesterone to develop into lobular alveolar structures prior to breeding.

The resting gland of unbred young rats has branching fine ductules, terminal end buds, and alveolar buds within a connective tissue stroma embedded in adipose tissue. Rat ducts and ductules are lined by one to two layers of cuboidal epithelium surrounded by a layer of myoepithelial cells adjacent to a basement membrane. The long axis of surrounding myoepithelial cells is arranged perpendicular to the epithelial cells, making them hard to visualize in standard H&E.

Males

Details of development in male rodents are less well documented. Androgens promote rudimentary bud atrophy in males through testosterone-induced condensation of the stroma. Unlike other mammals, rats exhibit sexual dimorphism in mammary gland development. In rats, mammary glands begin to develop in utero; however, differentiation into male and female mammary glands is not recognizable until the beginning of male pubertal development (day 35). Male rat duct growth ends by approximately 8 weeks of age.

Adult Gland at Rest

Mouse

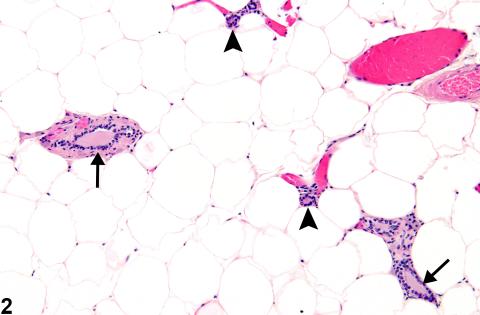

Female mouse mammary glands have a tubuloalveolar morphology characterized by an extensively branched ductal system embedded in the mammary fat pad (Figure 2). Tubular mammary ducts are lined by a pseudostratified low columnar or cuboidal epithelium in mice. Myoepithelial cells are interspersed between epithelial cells and the basement membrane in mice. Alveoli are lined by low cuboidal epithelium of several distinct, but immunologically related, cell types: basal (stem) cells, luminal epithelial cells, and myoepithelial cells. Mouse secretory alveolar cells are rich in ribosomes, Golgi complexes, lipid droplet, and secretory vacuoles. Lymphocytes in mouse mammary glands are predominantly helper T cells with fewer suppresser/cytotoxic T cells.

Figure 2. Mammary gland from a female B6C3F1 mouse. Widely separated duct profiles are embedded in abundant adipose tissue. Large ducts (arrows) branch into smaller ducts (arrow heads). Alveoli are rarely observed in histologic section.

Rats

In both sexes, myoepithelial cells surround a single or double layer of epithelium in the ducts, ductules, and alveoli. The epithelium is comprised of three types of epithelial cells (clear, dark, intermediate) that are differentiated by the relative quantities of different cytoplasmic components (ribosomes, mitochondria, lipid droplets, and secretory vacuoles).

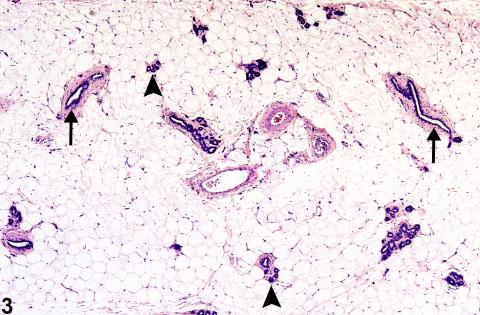

Unlike mice, the rat mammary gland displays sexual dimorphism. The resting female rat gland has prominent ducts with few alveoli (tubuloalveolar) (Figure 3). Compound tubuloalveolar glands in female rats are a highly branched system of ducts and terminal secretory alveoli arranged in lobules. The nipple, nipple canal, and nipple sinus are lined by squamous epithelium continuous with the epidermis

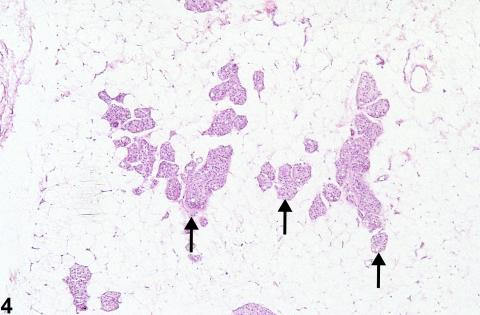

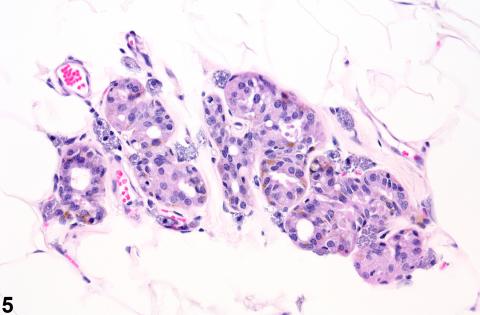

In contrast, male rats have relatively few ducts and prominent alveoli (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Male rat ducts are lined by vacuolated stratified epithelium with tall cuboidal to short column cells. Male rat alveoli contain stratified epithelial cells with abundant vacuolated, eosinophilic cytoplasm (lobuloalveolar architecture).

Figure 3. Mammary gland from a female F344/N rat. Ducts (arrows) are the most numerous components of the gland. Lobules of alveoli (arrowheads) are small and less frequently encountered in section.

Figure 4. Mammary gland from a male F344/N rat. Alveoli (arrows) are the most prominent structures and are lined by stratified vacuolated epithelium. Ducts (not shown) are less numerous in histologic section than in females.

Figure 5. Mammary gland from male Harlan Sprague-Dawley rat. Alveoli with epithelial cells containing pigment within abundant white adipose tissue.

Pregnancy and lactation

In mice, alveolar development occurs during pregnancy and is regulated by prolactin, GH, and ACTH. Placental hormones alone can also maintain mammary gland growth. Once pups are weaned, the secretory epithelial cells undergo degeneration, and alveoli are reduced to clusters of epithelial cells without a central lumen.

In rats during pregnancy and lactation, the alveolar lobules are formed from rapid TEB differentiation. Once lactation is complete, the gland regresses, but looks different than virgin rats of the same age.

Senescence

Rodent mammary gland involution generally begins after 1 year of age. Senescent glands from virgin rats in some strains may have inappropriate secretory activity. Increased prolactin secretion can lead to duct ectasia and subsequent cyst/galactocele formation, epithelial hyperplasia, and periductal fibrosis. In mice, gland involution is characterized by distal duct atrophy, with the main ducts and a few secondary branches remaining visible.

Normal variations of the mammary gland

Mammary glands of a growing male rat can have tubuloalveolar morphology (female type) before differentiating into the lobuloalveolar pattern (male type). Therefore, a section with both morphologies adjacent to each other in a growing male rat can give a false impression of female pattern of differentiation. Weak estrogens or low doses of strong estrogens can produce a mixture of male and female differentiation, but the altered structures should be spread throughout the gland.

Also, newly growing buds should be carefully differentiated from foci of epithelial hyperplasia (Lucas, et al., 2007). Another age-related normal change is partial conversion of male to female pattern of glandular differentiation, probably due to an age-related increase in prolactin secretion. Hence, age should be considered while making treatment-related effect decisions (Lucas, et al., 2007).

Information on the following lesions is available in this section:

Schwartz CL, Christiansen S, Hass U, Ramhøj L, Axelstad M, Löbl NM, Svingen T. 2021. On the use and interpretation of areola/nipple retention as a biomarker for anti-androgenic effects in rat toxicity studies. Front Toxicol 3:730752.

Tucker DK, Foley JF, Hayes-Bouknight SA, Fenton SE. 2016. Preparation of high-quality hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections from rodent mammary gland whole mounts for histopathologic review. Toxicol Pathol 44(7):1059-64.

Vidal JD, Filgo AJ. 2017. Evaluation of the estrous cycle, reproductive tract, and mammary gland in female mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 7(4):306-325.

Greaves P. 2012. Mammary gland. Histopathology of preclinical toxicity studies, 4 ed. Academic Press pp. 69-97.

Cardiff RD, Jindal S, Treuting PM, Going JJ, Gusterson B, Thompson HJ. 2018. Mammary gland. In: Comparative anatomy and histology, 2nd ed. Treuting PM, Dintzis SM, Montine KS. (eds). Academic Press pp. 487-509.

Eighmy JJ, Sharma AK, Blackshear PE. 2018. Mammary gland. In: Boorman's Pathology of the rat, 2nd ed. Suttie AW (ed.). Academic Press 369-388.

Rudmann D, Cardiff R, Chouinard L, Goodman D, Küttler K, Marxfeld H, Molinolo A, Treumann S, Yoshizawa K. 2012. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse mammary, Zymbal's, preputial, and clitoral glands. Toxicol Pathol 40(6 Suppl):7S-39S.

Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22949413Herbert R, Pandiri AR, Malarkey DE, Cesta MF, Elmore SA. 2023. Anatomic pathology. In: Specifications for the conduct of toxicity studies by the Division of Translational Toxicology at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Roberts GK, Stout MD). Chapter 8:1-63 (https://

Lucas JN, Rudmann DG, Credille KM, Irizarry AR, Peter A, Snyder PW. 2007. The rat mammary gland: morphologic changes as an indicator of systemic hormonal perturbations induced by xenobiotics. Toxicol Pathol 35:199-207.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17366314