Integumentary System

Mammary Gland - Inflammation

Narrative

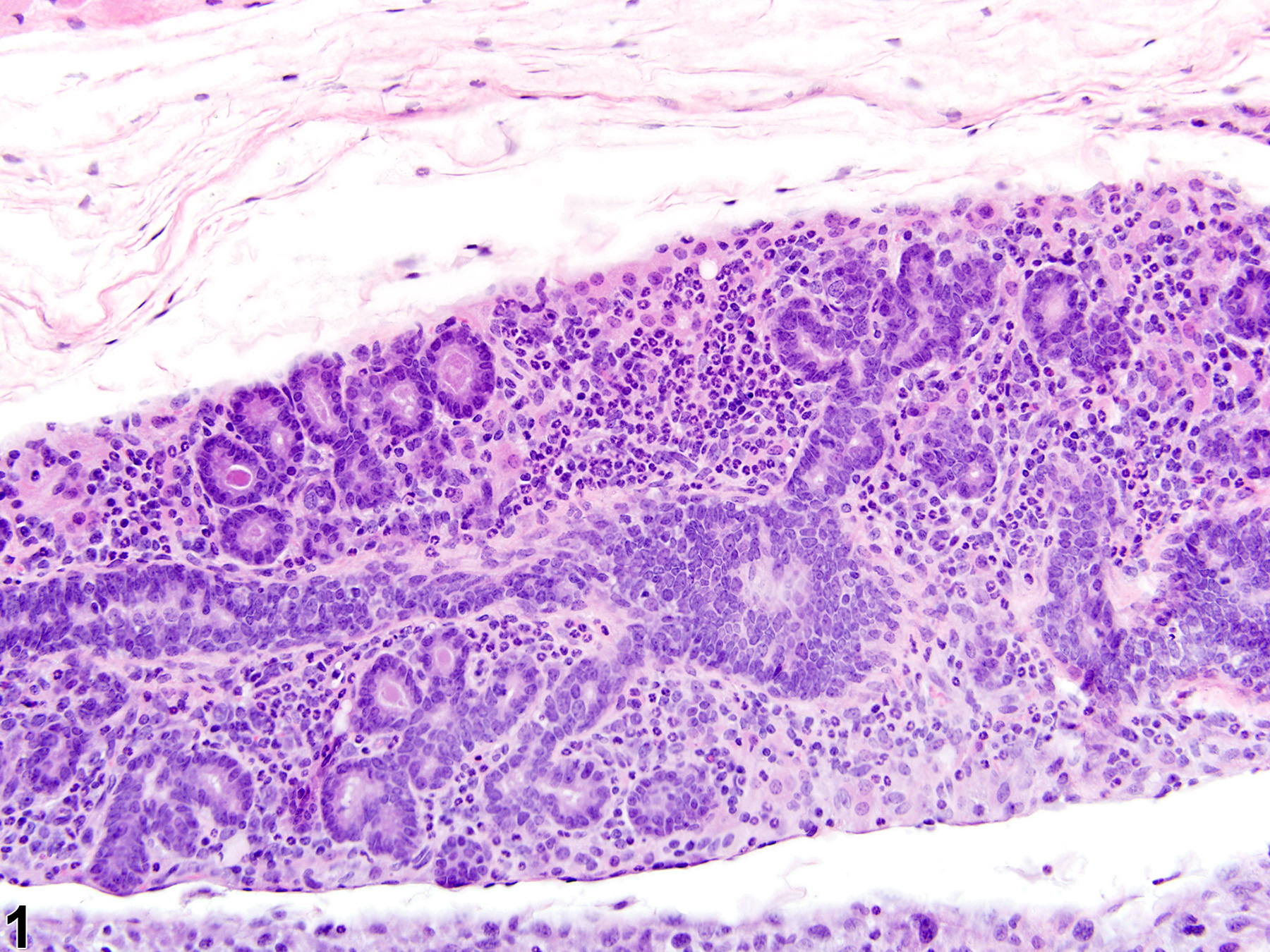

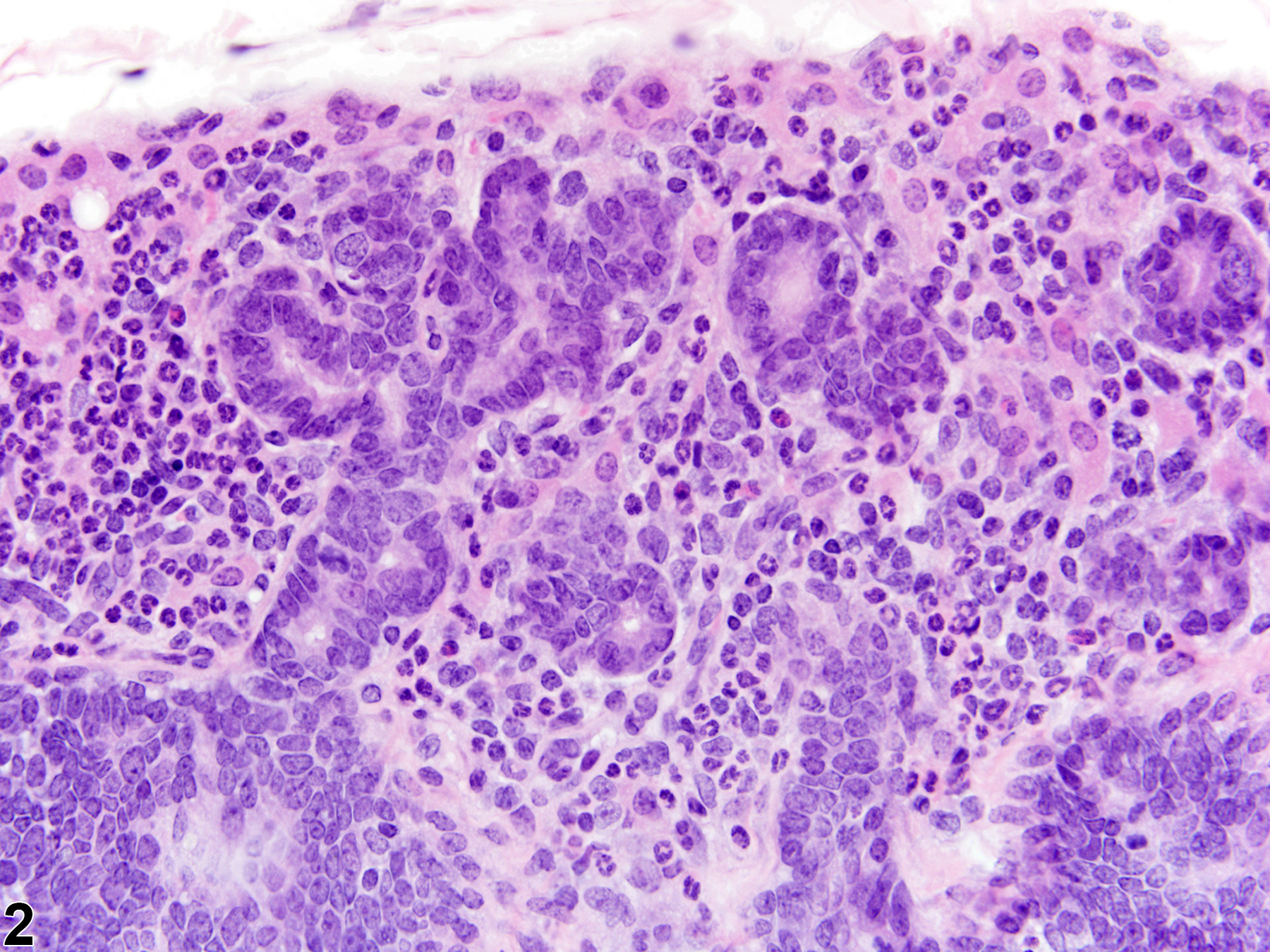

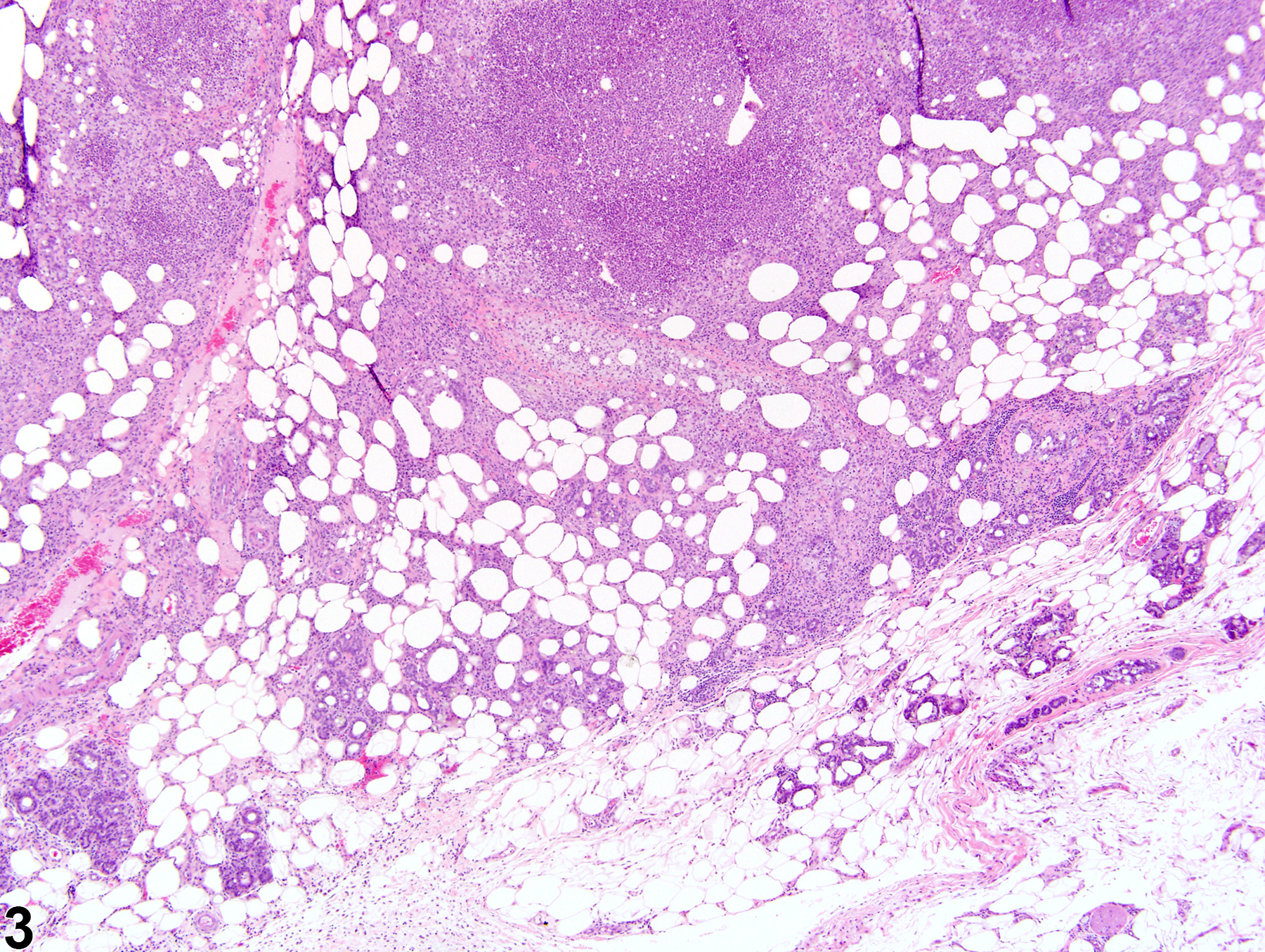

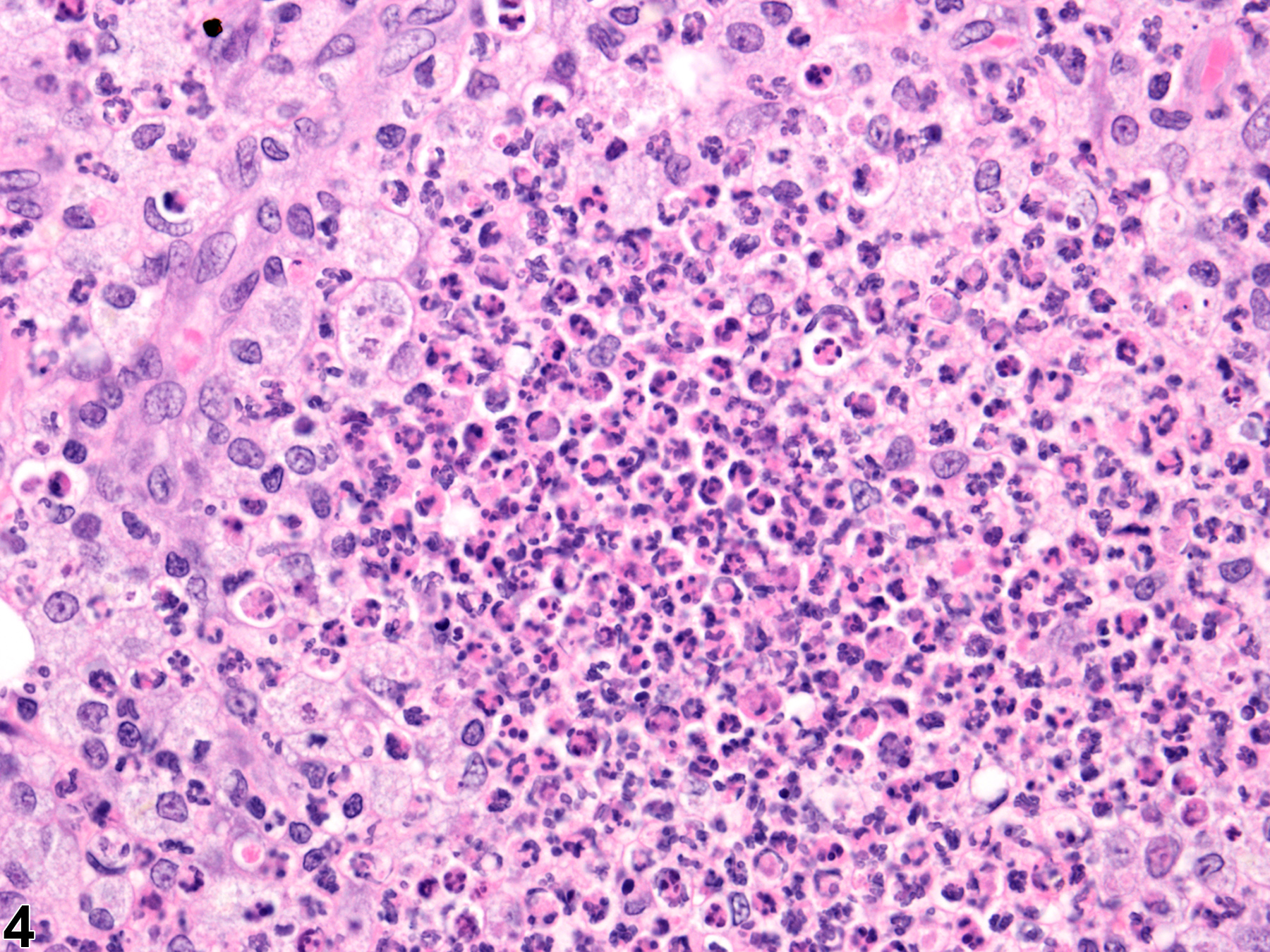

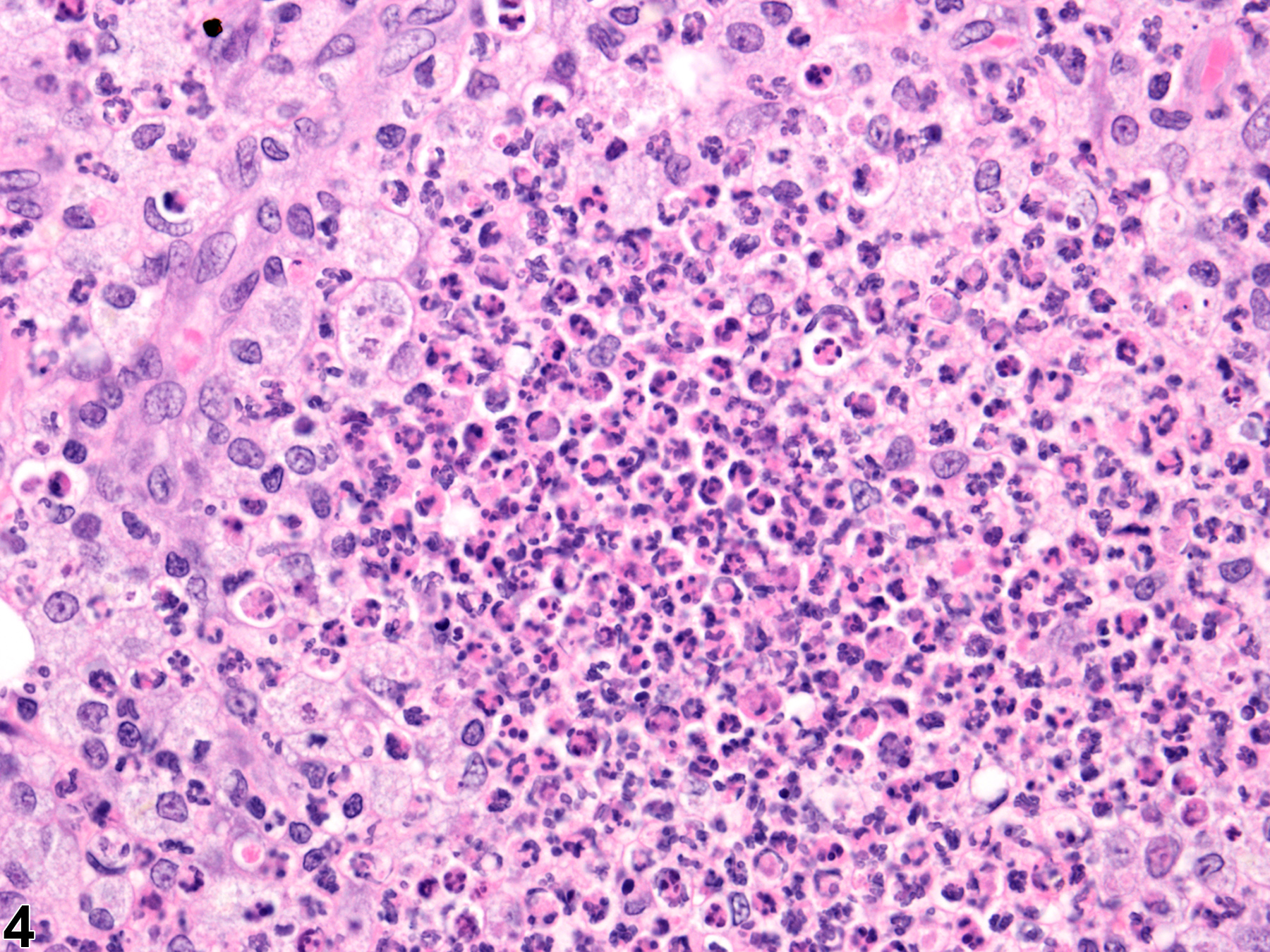

Acute inflammation (Figure 1 and Figure 2) in the mammary gland is characterized by infiltration of neutrophils, which may be accompanied by eosinophils and, to a lesser extent, macrophages, mast cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. These cellular infiltrates are generally accompanied by vascular congestion; edema; the accumulation of serous, mucous, or fibrinous exudates; and sloughed epithelial cells in tubular and/or alveolar lumina. Suppurative inflammation (Figure 3 and Figure 4) of the mammary gland is characterized by discrete pockets of degenerate neutrophils and cellular debris. Evidence of chronicity, such as fibrosis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, may also surround these pockets. Chronic inflammation of the mammary gland is characterized by the presence of mononuclear cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages) and may be accompanied by epithelial cell regeneration, hyperplasia and/or metaplasia, and fibrosis. Chronic active inflammation of the mammary gland is characterized by the coexistence of elements of chronic inflammation (lymphocytes, macrophages, regeneration, hyperplasia, and fibrosis) and superimposed acute inflammation (neutrophilic and/or eosinophilic). Granulomatous inflammation is characterized by an accumulation of plump macrophages (epithelioid cells) organized in interlacing bundles, with variable numbers of multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, or neutrophils and may be accompanied by fibrosis epithelial cell regeneration, hyperplasia, and/or metaplasia. Granulomatous inflammation is commonly seen in rats associated with rupture of dilated ducts. Other etiologic agents may be present and induce inflammatory changes (e.g., fungi, foreign bodies, etc.). All forms of inflammation may be accompanied by associated lesions, including edema (though this is more commonly associated with acute inflammation), epithelial hyperplasia, neovascularization, or hemorrhage with or without hemosiderin-containing macrophages.

Devor DE, Waalkes MP, Goering P, Rehm S. 1993. Development of an animal model for testing human breast implantation materials. Toxicol Pathol 21(3):261-73.

Abstract: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8248715Greaves P. 2007. Mammary gland. Histopathology of preclinical toxicity studies. Interpretation and relevance in drug safety evaluation, 3rd ed. Academic Press pp. 68-98.

Rehm S, Liebalt AG. Nonneoplastic and neoplastic lesions of the mammary gland. In: Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Ward J, Capen CC, Carlton WW, Sundberg JP (eds.). 1996. Pathobiology of the aging mouse, Vol. 2. International Life Sciences Institute Press pp. 381-398.

Tucker MJ. 1997. The integumentary system and mammary glands. Diseases of the Wistar rat. CRC Press pp. 23-36.

Van Zwieten MJ, HogenEsch H, Majka JA, Boorman GA. Nonneoplastic and neoplastic lesions of the mammary gland. In: Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Capen CC (eds.). 1994. Pathobiology of the aging rat, Vol. 2. International Life Sciences Press pp. 459-474.

Mammary gland - Inflammation chronic active in a female F344/N rat from a chronic study (higher magnification of Figure 3). Inflammatory cell infiltrates of mixed accumulations of neutrophils and macrophages are present in the mammary gland.

Mammary gland - Inflammation chronic active in a female F344/N rat from a chronic study (higher magnification of Figure 3). Inflammatory cell infiltrates of mixed accumulations of neutrophils and macrophages are present in the mammary gland.