Alimentary System

Stomach, Forestomach - Erosion

Narrative

Bertram TA, Markovits JE, Juliana MM. 1996. Non-proliferative lesions of the alimentary canal in rats GI-1. In Guides for Toxicologic Pathology. STP/ARP/AFIP, Washington, DC, 1-16.

Full Text: https://www.toxpath.org/docs/SSNDC/GINonproliferativeRat.pdfBetton GR. 1998. The digestive system I: The gastrointestinal tract and exocrine pancreas. In: Target Organ Pathology (Turton J, Hooson J, eds). Taylor and Francis, London, 29-60.

Brown HR, Hardisty JF. 1990. Oral cavity, esophagus and stomach. In: Pathology of the Fischer Rat (Boorman GA, Montgomery CA, MacKenzie WF, eds). Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 9-30.

Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/9002563Leininger JR, Jokinen MP, Dangler CA, Whiteley LO. 1999. Oral cavity, esophagus, and stomach. In: Pathology of the Mouse (Maronpot RR, ed). Cache River Press, St Louis, MO, 29-48.

Puurunen J, Huttunen P, Hirvonen H. 1980. Is ethanol-induced damage of the gastric mucosa a hyperosmotic effect? Comparative studies on the effects of ethanol, some other hyperosmotic solutions, and acetyl-salicylic acid on rat gastric mucosa. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 47:321-327.

Abstract: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1600-0773.1980.tb01567.x/abstract

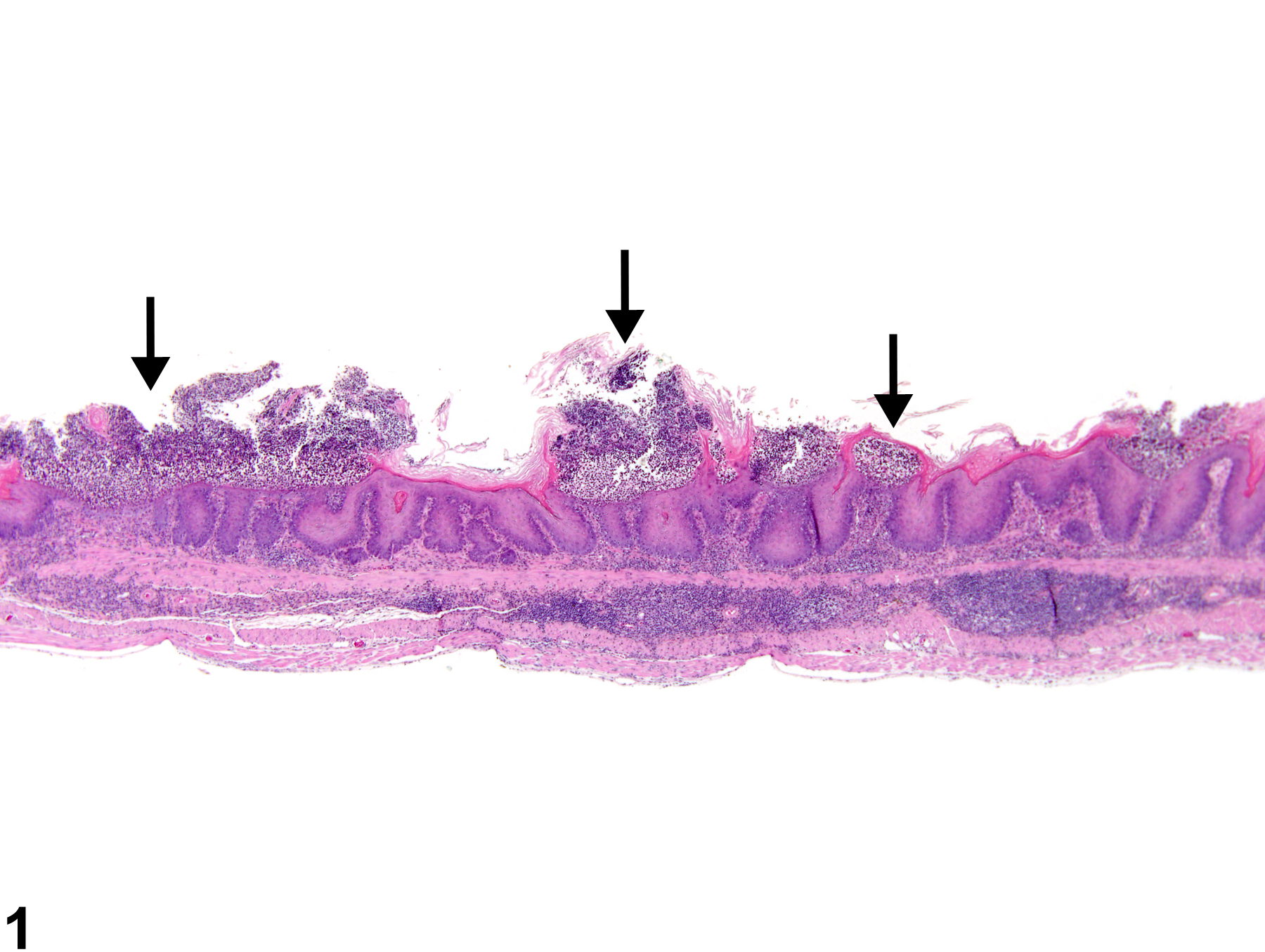

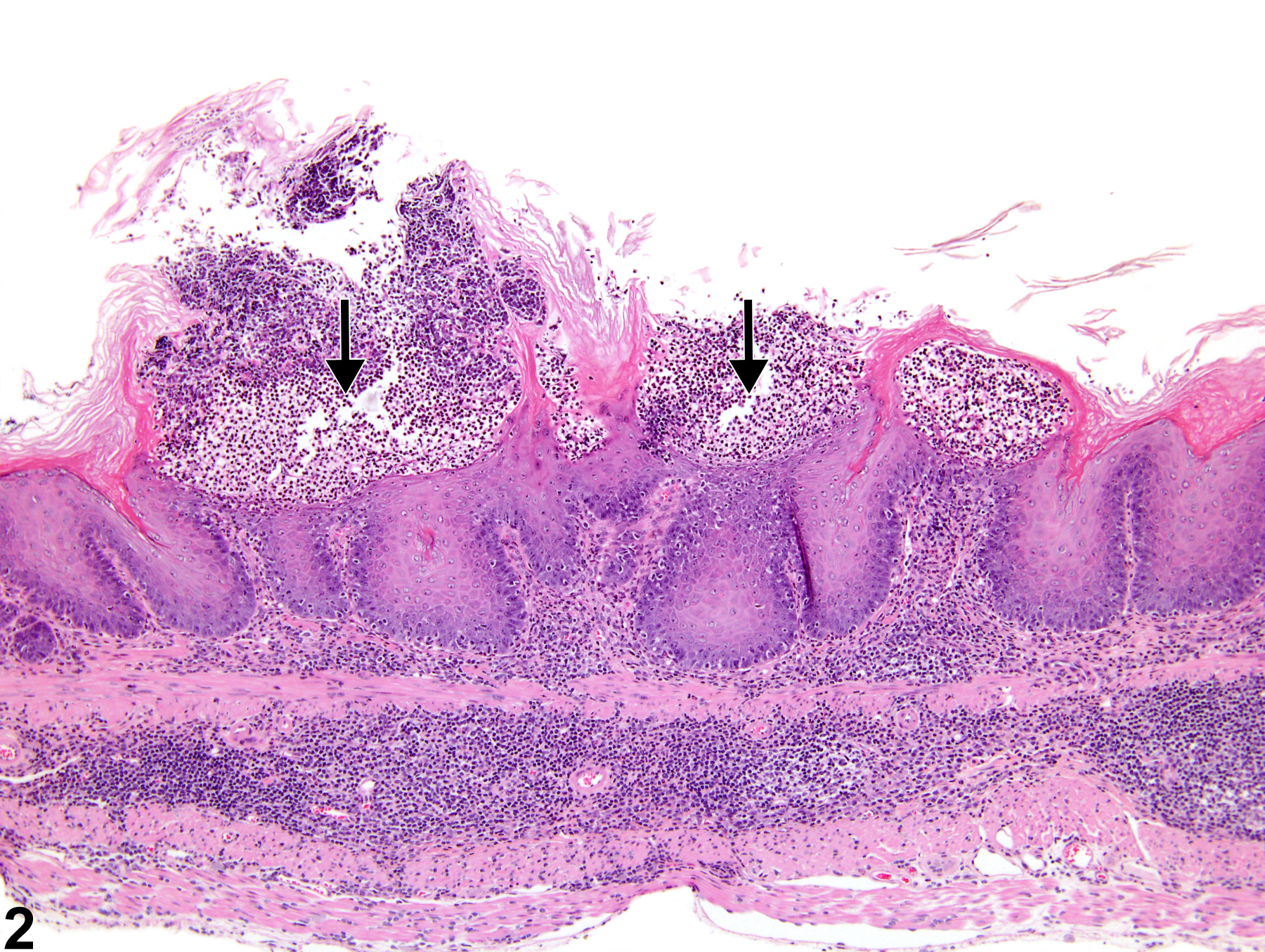

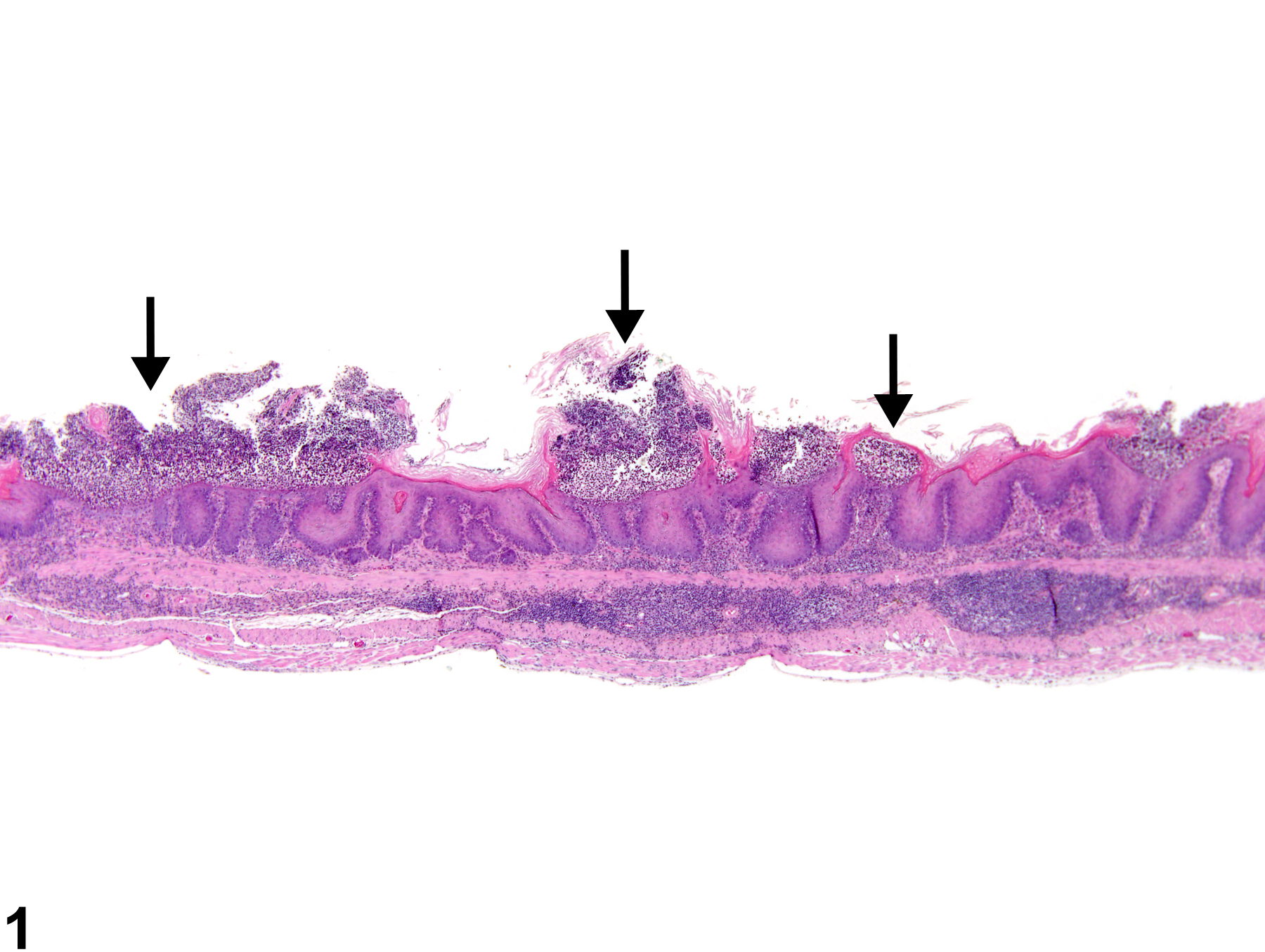

Stomach, Forestomach - Erosion in a female B6C3F1 mouse from a chronic study. The superficial layers of the hyperplastic squamous epithelium have been lost (arrows).