Integumentary System

Mammary Gland - Hyperplasia

Narrative

Normally, the greatest degree of mammary gland proliferation and secretory activity in female rats and mice results from pregnancy and lactation; similar changes can also occur in pseudopregnant females. Physiological mammary gland proliferation can also exhibit some variation depending on the stage of the estrous cycle, with most available studies reporting the most prominent lobular and alveolar development in metestrus and early diestrus.

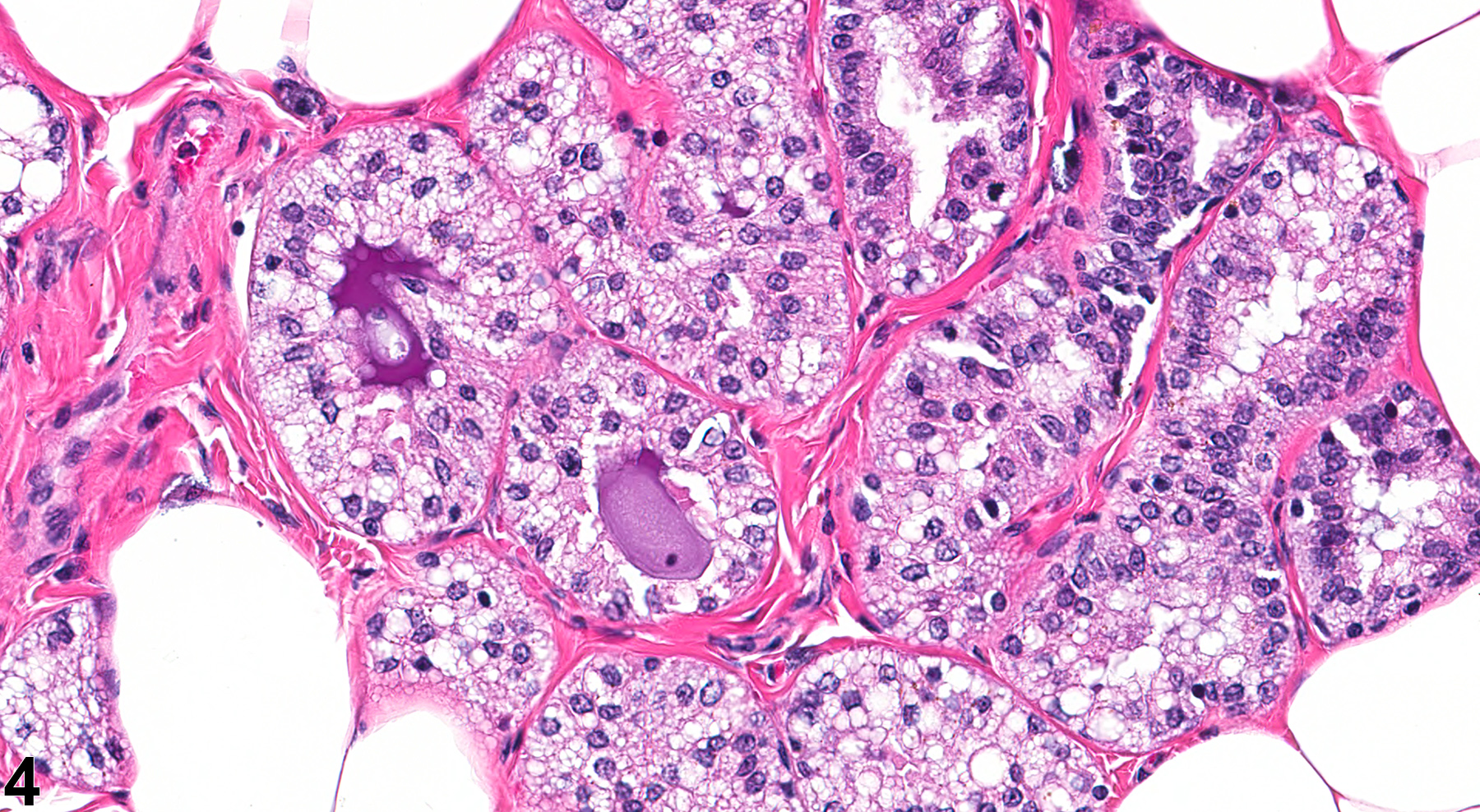

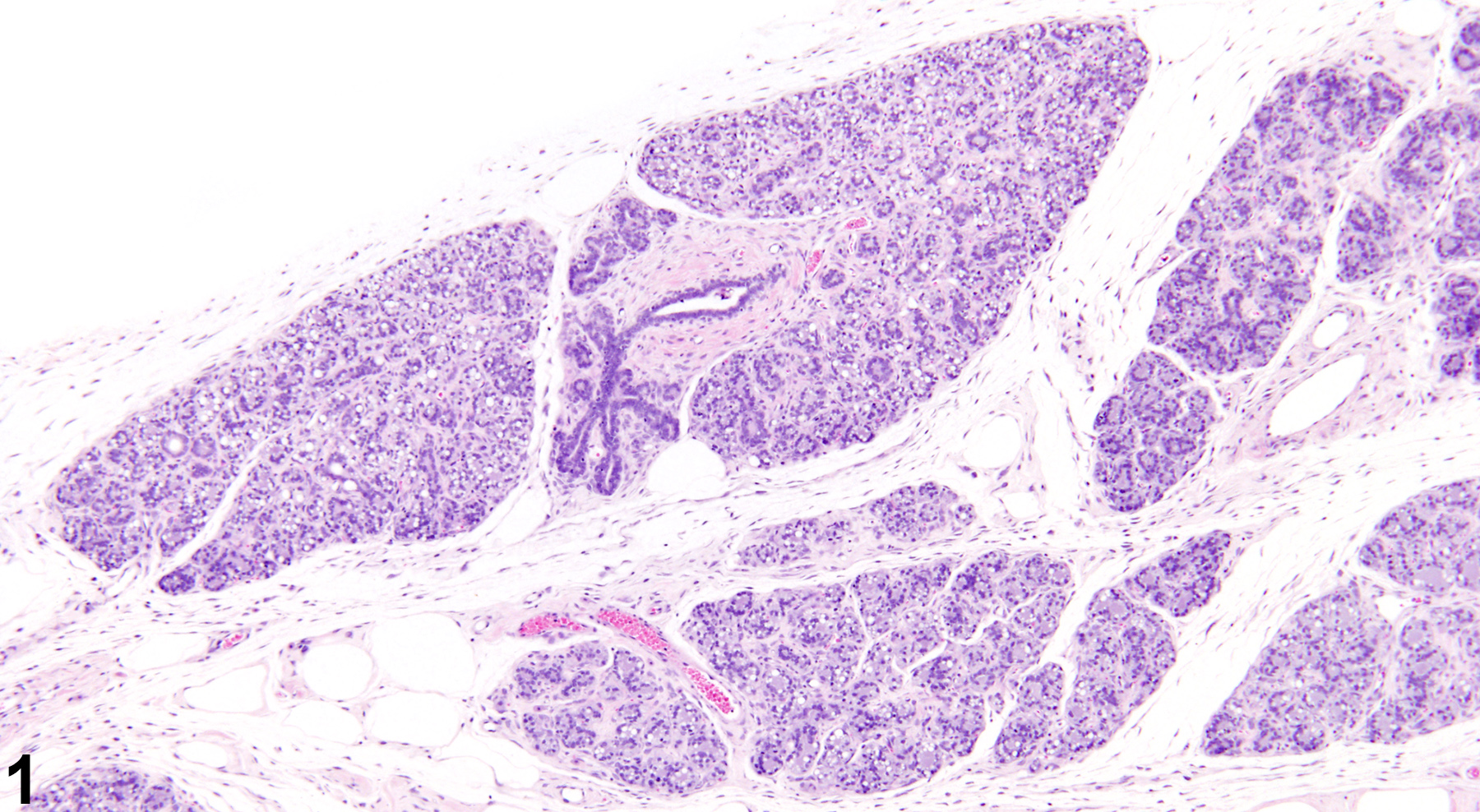

Nonphysiological, spontaneously occurring mammary gland hyperplasia of uncertain etiology is a common aging change in virgin rats and mice, and can occur in both sexes. Mammary gland hyperplasia can also result from ovarian or pituitary hormone imbalances, which can be primarily or secondarily induced by factors such as exogenous toxins and nutrient deficiencies. Hyperplasia can also be a precursor to mammary gland neoplasia (spontaneous or treatment-related). Lobular hyperplasia (Figure 1 and Figure 2) can be focal or diffuse and is characterized by enlarged lobules with increased numbers of relatively normal alveoli. Ducts are typically not affected. Depending on the amount of intraluminal secretions, the affected alveoli may have a variable diameter but are lined by a single layer of well-differentiated cells. Reactive fibrous stroma is usually present, with amounts ranging from rather scanty to more extensive. However, the lack of both compression and a prominent collagenous stroma are features that distinguish lobular hyperplasia from fibroadenoma. As well as being a treatment-related or aging change, lobular hyperplasia in females can be a physiological change occurring during pregnancy and lactation, a result of xenobiotics that cause hyperprolactinemia, as well as in pseudopregnant animals. Lobular (alveolar) hyperplasia may be a precursor of adenoma, fibroadenoma, or adenocarcinoma. However, chemically induced hyperplastic lobules do not appear to be precursors to adenocarcinoma.

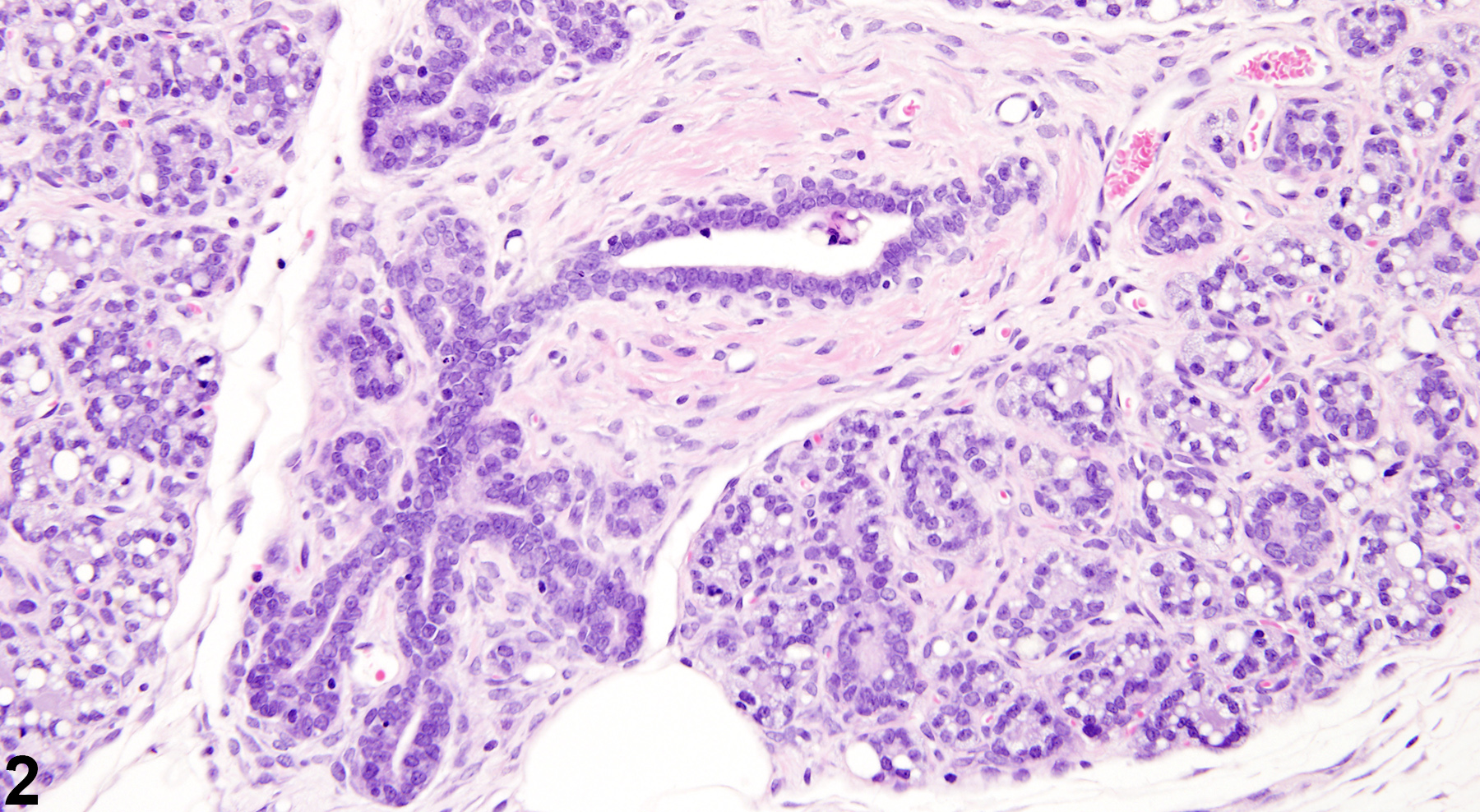

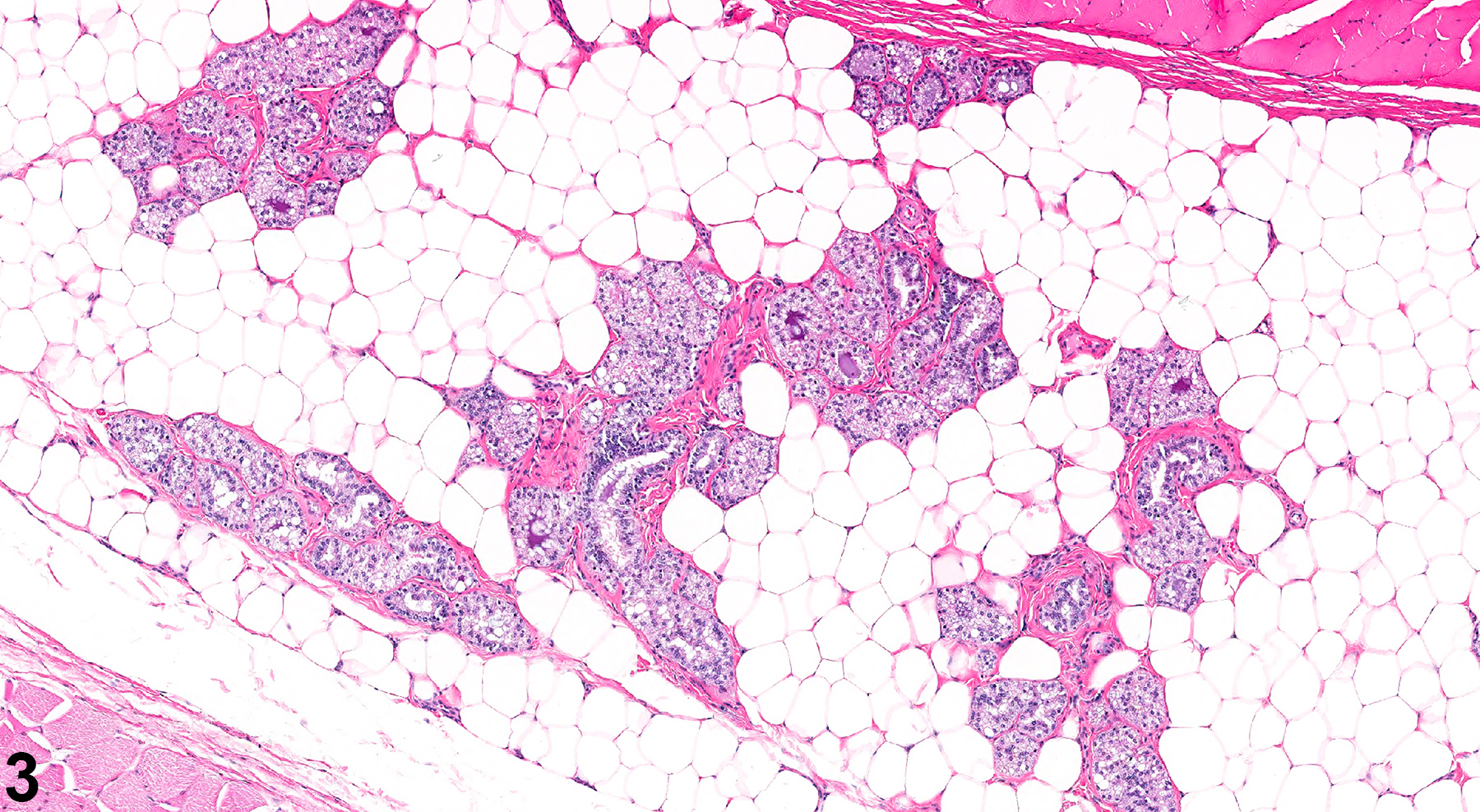

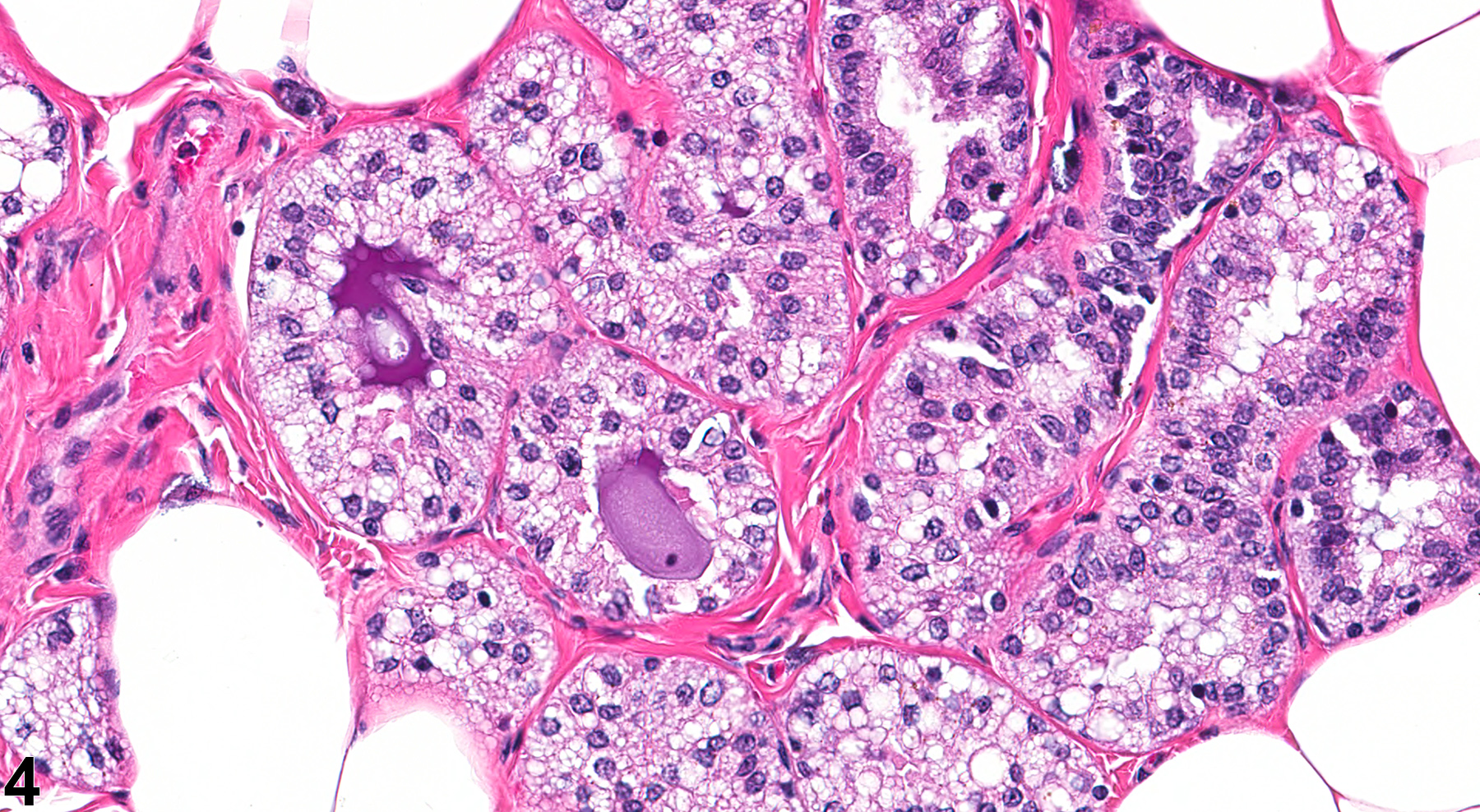

Male mice and rats normally have abundant mammary gland tissue, which can also undergo spontaneous or treatment-related hyperplasia. Unlike mice and other species, the mammary glands of rats exhibit sexual dimorphism, with glands in non-pregnant and non-lactating females having a tubuloalveolar morphology, while males exhibit a lobuloalveolar appearance. Thus, administration of certain agents (androgens, anabolic steroids, etc.) to female rats can result in the alteration of the mammary gland morphology to the typical male-like lobuloalveolar morphology (“masculinization” or “virilization”). Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the mammary gland with a lobulolalveolar pattern (similar to that in control males) from a female rat dosed with oxymetholone (an anabolic steroid) for 13 weeks; the appearance is quite different from the usual female tubuloalveolar morphology observed in control female rats from the same study.

Conversely, administration of other agents (estrogens, prolactin, compounds such as dopaminergic receptor antagonists that indirectly result in hyperprolactinemia, etc.) can result not only in mammary gland hyperplasia in male and female rats, but also in female-like tubuloalveolar mammary gland morphology (“feminization”) in male rats.

| Andrews P, Freyberger A, Hartmann E, Eiben R, Loof I, Schmidt U, Temerowski M, Folkerts A, Stahl B, Kayser. 2002. Sensitive detection of the endocrine effects of the estrogen analogue ethinylestradiol using a modified enhanced subacute rat study protocol (OECD Test Guideline no. 407). Arch Toxicol. 76(4):194-202. |

| Barsoum NJ, Gough AW, Sturgess JM, de la Iglesia FA. 1984. Morphologic features and incidence of spontaneous hyperplastic and neoplastic mammary gland lesions in Wistar rats. Toxicol Pathol 12(1):26-38. |

| Boorman GA, Wilson JT, Van Zwieten M, Eustis SL. 1990. Mammary gland. In: Boorman GA, Eustis SL, Elwell MR, Montgomery CA, Mackenzie WF (eds.). 2016. Pathology of the Fischer rat - reference and atlas. Academic Press pp. 295-313. |

| Burek JD. 1978. Pathology of aging rats. CRC Press pp. 163-167. |

| Cardy RH. 1991. Sexual dimorphism of the normal rat mammary gland. Vet Pathol 28(2):139-45. |

| El Sheikh Saad H, Meduri G, Phrakonkham P, Berges R, Vacher S, Djallali M, Auger J, Canivenc-Lavier MC, Perrot-Applanat M. 2011. Abnormal peripubertal development of the rat mammary gland following exposure in utero and during lactation to a mixture of genistein and the food contaminant vinclozolin. Repro Toxicol 32(1):15-25. |

| Eskin BA, Grotkowski CE, Connolly CP, Ghent WR. 1995. Different tissue responses for iodine and iodide in rat thyroid and mammary glands. Biol Trace Element Res 49(1):9-19. |

| Fata JE, Chaudhary V, Khokha R. 2001. Cellular turnover in the mammary gland is correlated with systemic levels of progesterone and not 17β-estradiol during the estrous cycle. Biol Reprod 65(3):680-8. |

| Foster WG, Younglai EV, Boutross-Tadross O, Hughes CL, Wade MG. 2004. Mammary gland morphology in Sprague-Dawley rats following treatment with an organochlorine mixture in utero and neonatal genistein. Toxicol Sci 77(1):91-100. |

| Goodman DG, Ward JM, Squire RA, Chu KC, Linhart MS. 1979. Neoplastic and nonneoplastic lesions in aging F344 rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 48(2):237-248. |

| Greaves P. 2007. Mammary gland. Histopathology of preclinical toxicity studies. Interpretation and relevance in drug safety evaluation, 3rd ed. Academic Press pp. 68-98. |

| Harvell DME, Strecker TE, Tochacek M, Xie B, Pennington KL, McComb RD, Roy SK, Shull JD. 2000. Rat strain-specific actions of 17β-estradiol in the mammary gland: correlation between estrogen-induced lobuloalveolar hyperplasia and susceptibility to estrogen-induced mammary cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97(6):2779-2784. |

| Hvid H, Thorup I, Sjögren I, Oleksiewicz MB, Jensen HE. 2012. Mammary gland proliferation in female rats: effects of the estrous cycle. Exp Toxicol Pathol 64(4):321-32. |

| Latendresse JR, Bucci TJ, Olson G, Mellick P, Weis CC, Thorn B, Newbold RR, Delclos KB. 2009. Genistein and ethinyl estradiol dietary exposure in multigenerational and chronic studies induce similar proliferative lesions in mammary gland of male Sprague-Dawley rats. Reprod Toxicol 28(3):342-53. |

| Lucas JN, Rudmann DG, Credille KM, Irizarry AR, Peter A, Snyder PW. 2007. The rat mammary gland: morphologic changes as an indicator of systemic hormonal perturbations induced by xenobiotics. Toxicol Pathol 35:199-207. |

| Masso-Welch PA, Darcy KM, Stangle-Castor NC, Ip MM. 2000. A developmental atlas of rat mammary gland histology. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 5(2):165-85. |

| Okuda M, Takahishi H, Oyaizu T, Tsubura A, Morii S, Oishi Y, Fujii T. 1992. Morphological observations on sexual dimorphism in rat mammary glands. J Toxicol Pathol 5:205-214. |

| Rehm S, Liebalt AG. Nonneoplastic and neoplastic lesions of the mammary gland. In: Mohr U, Dungworth DL, Ward J, Capen CC, Carlton WW, Sundberg JP (eds.). 1996. Pathobiology of the aging mouse, Vol. 2. International Life Sciences Institute Press pp. 381-398. |

| Russo IH, Medado J, Russo J. Endocrine influences on the mammary gland. In: Jones TC, Mohr U, Hunt RD (eds.). 1989. Integument and mammary glands (monographs on pathology of laboratory animals). International Life Sciences Institute pp. 252-266. |

| Schedin P, Mitrenga T, Kaeck M. 2000. Estrous cycle regulation of mammary epithelial cell proliferation, differentiation, and death in the Sprague-Dawley rat: a model for investigating the role of estrous cycling in mammary carcinogenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 5(2):211-25. |

| Seely JC, Boorman GA. Mammary gland and specialized sebaceous glands. In: Maronpot RR, Boorman GA, Gaul BW (eds.). 1999. Pathology of the mouse: reference and atlas. Cache River Press pp. 613-635. |

| Sourla A, Martel C, Labrie C, Labrie F. 1998. Almost exclusive androgenic action of dehydroepiandrosterone in the rat mammary gland. Endocrinology 139(2):753-64. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9449650 |